By Sandra Schulman

The Art Nouveau movement in turn-of-the-century Paris flourished with graceful elaborate lines, embellished flora and fauna, and romantic femme fatales advertising — cocaine? Rolling papers? Alcohol?

Hedonism indeed.

The head of this heady movement was Alphonse Mucha, whose work is featured in the exhibition Alphonse Mucha: Master of Art Nouveau at the Flagler Museum, now on view through April 14.

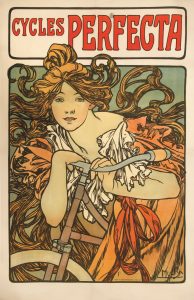

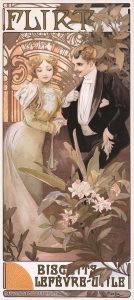

The exhibition is a tribute to Mucha’s bold work and the environment that nurtured him in 19th-century Paris. But there are surprising elements at play here — his elaborate advertising work plugged everything from bicycles to beer to “coca tonic.”

“In this exhibition, we embark on a discerning exploration of the luminous intersections between Alphonse Mucha, the paramount figure of Art Nouveau, and the evanescent tapestry of the Gilded Age in Paris,” writes associate curator Campbell Mobley. “Within these hallowed halls, we traverse the convoluted landscapes of an era that resonates with opulence, innovation, and aesthetic revolution.”

“As we delve into Mucha’s oeuvre, we encounter not merely the brushstrokes of a virtuoso, but a narrative that unveils the synthesis of artistic brilliance and societal metamorphosis,” Mobley writes, noting that the artist’s ascent mirrored the city’s flowering as a hotbed of culture that reacted to the pressures of industrialization.

As evolved as his work was, he struggled in his early years. Mucha was born in 1860 in Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), where his father Ondrej worked as an usher at the Ivancice courthouse. Mucha could draw before he could walk but he failed to gain entry to study at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, so he took a job creating advertisements for theatrical scenery in Vienna.

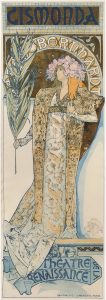

He eventually made his way to study at the Academy of Art in Munich for two years, then on to Paris in 1887, providing his lush illustrations for a variety of magazines and books. His breakthrough real-life goddess was Sarah Bernhardt, the star of the Parisian stage, who called for a new poster for her production of Gismonda. All the usual artists were on holiday, so the owner asked Mucha in desperation.

Gismonda, the poster Mucha created, and which is on display here in various location versions, revolutionized poster design. He used a long narrow shape, subtle pastel colors and a glowing “halo” effect around Bernhardt’s head, an iconograpic fingerprint he was to retain the rest of his life. The poster’s effect was astonishing: So popular was it with the Parisian public that collectors bribed poster hangers for them or just went out at night and cut them down from the theater displays.

During the next 10 years, Mucha became one of the most popular and successful Parisian artists as commissions flooded in for theater posters, ad posters, decorative panels, magazine covers, menus, postcards, even calendars.

On display in cases at the Flagler are some of his extended designs for jewelry, cutlery, tableware, and boxes. The exhibit itself is displayed in three rooms, a lush environment with deep lilac-painted walls bordered with snakey floral shapes taken from the wooden carved and metal cast frames of the artwork.

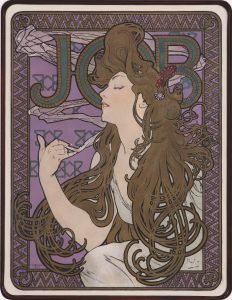

The surprising designs for Job rolling papers in 1898 became an instant classic, still used today by the company, hanging in museums and copied in ads for album covers and other products. What was being rolled in them was probably tobacco at first, but the intoxicating image translated to the marijuana culture.

“This exhibition is not a mere homage to aesthetics. It is an intellectual exploration of Mucha’s profound connection to Slavic nationalism, epitomized by his magnum opus, ‘The Slav Epic,’” Mobley writes. “This series serves as a nuanced testament to the symbiotic relationship between art and identity during an epoch where societal narratives crystallized in the artistry of the brush.”

Beyond the ad work and despite his commercial successes, Mucha did not have much in the way of savings — he gave money away to help out friends and causes, and he collected objects for his studio and entertaining.

Charles Crane, an American millionaire with a love for Slavic culture, funded Mucha’s ambitious Slav Epic, a series of paintings depicting the history of the Slavic tribes. Mucha spent the remainder of his life creating 20 large paintings that make up the Slav Epic. The canvases were completed and in 1928 Mucha and Charles Crane officially presented them as a gift to the city of Prague.

The allure of Mucha’s work still lies in the zone between the mystical and the modern. Nature, European mythology, and the idealized female form swirled in his compositions, mirroring the era’s fascination with spiritualism and the occult. He created a world where they meet in a mosaic of beauty and mysticism.

Alphonse Mucha: Master of Art Nouveau will be on view through April 14 at the Flagler Museum, 1 Whitehall Way, Palm Beach. Tickets: $26, $13 for children ages 6-12. Hours: Tuesday through Saturday, 10 am to 5 pm; Sunday, noon to 5 pm. Call 561-655-2833 or visit flaglermuseum.us for more information.