By April W. Klimley

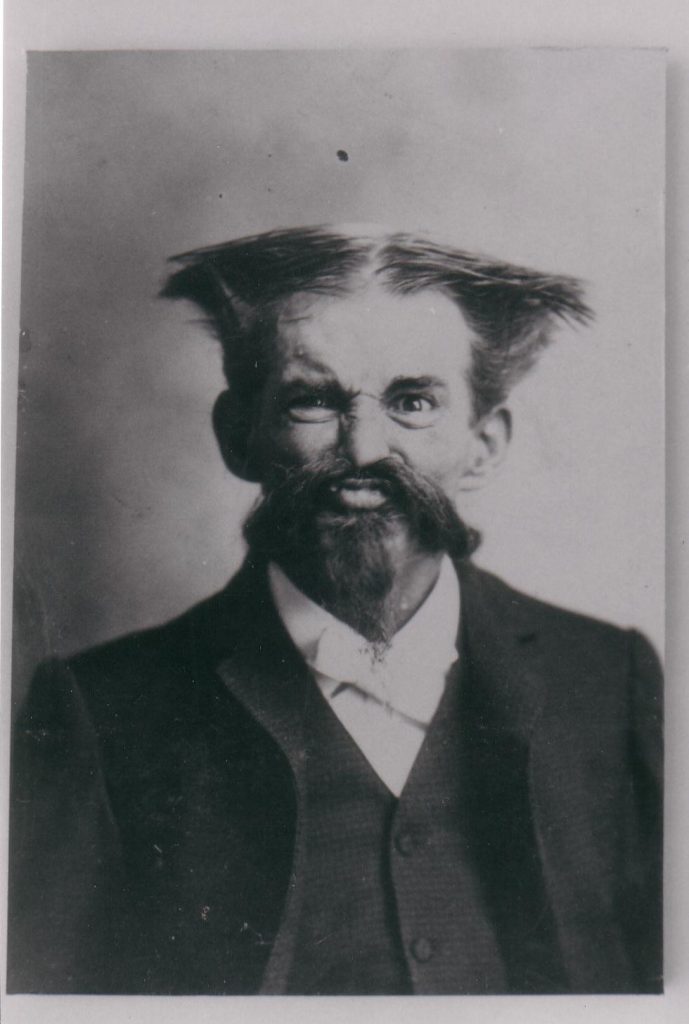

More than 100 years ago, the ceramicist George Ohr (1857-1918) was called the “mad potter” of Biloxi, Miss. Today he is venerated as a precursor of abstract expressionism and his work goes for anywhere from $60,000-$70,000 apiece.

His strangely shaped, broken, highly glazed works are also an inspiration for many ceramicists around the world today. That influence is visible in the works of art displayed in the Boca Raton Museum exhibition titled Regarding George Ohr: Contemporary Ceramics in the Spirit of the Mad Potter, which opens Tuesday and runs through April 8.

Walking into the show, viewers will immediately see a fine selection of the strange, starling works by Ohr – many from the 400-piece collection of Marty and Estelle Shack of Boynton Beach, and rarely (if ever) seen by the public. Following that first act of the exhibition are works by 18 other ceramic artists from around the globe selected by Garth Clark, a top expert in the field of ceramics and one of the critics who helped rebuild Ohr’s reputation decades ago.

In assembling the exhibition, Clark says he was looking for artists “whose work continues the legacy of Ohr without copying it.” As a result, he says, “What we’ve ended up with is a show that is not pretty in the conventional sense for the viewer.”

The exhibition does contain a number of moody, abstract pieces. Many of them echo Ohr’s delight in collapsing and breaking forms deliberately. But it also contains some surprises where the artists have creating something that borders on the beautiful and joyous – something Ohr never aspired to.

But before viewing the 18 contemporary ceramicists in the show, it’s worthwhile to stop and examine the Ohr pieces in the entrance gallery. The room contains a few pieces from his early work, so viewers can see how he started out in a somewhat conventional way, with the exception of the gleaming glazes that flow over even these vessels.

More exciting are the pieces – virtually all from the Shack collection – which he created in the last decade of the 19th century. These vessels may have started out as vases or cups, but they end up split, twisted or even broken. Many have amazingly thin walls, which no one has been able to replicate, completely covered with Ohr’s distinctive iridescent glazes.

You can see the transition from the traditional to this newer vision in Ohr’s Two-Handled Dark Red with Green Vase (1895-1900). Its shape is reminiscent of a Persian pitcher, but the handles slither and twist like snakes on either side. The (green) glaze glows as if it were glass, but the vessel makes a much more powerful statement than would in that sister medium.

That vase is a good introduction to the work of Ken Price, one of the other artists in the exhibition. His piece, titled FEW, echoes the flailing arms of Ohr’s pitcher, but in an entirely different way. It’s a piece of sculpture – not a vessel – which resembles a dark red octopus with tentacles holding it up and a blank eye in the center. Unlike the Ohr piece, this sculpture is both challenging and playful, daring the viewer to grab one of its arms and play.

Several artists in the show convey darker visions, more closely resembling the spirit of Ohr’s work – “organic forms, collapsing and breaking … a kind of adventure with the vessel, taking it into realms that are non-formalist,” Clark said. These pieces include the fuzzy, bent-over cylindrical creatures in yellow or brown of Anne Marie Laureys. Even though one is entitled Angels Kissing the Ground, as a group they somehow resemble the dwarves in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Sure enough, the third piece is even titled Snow White (the dwarfs are out there).

Takuro Kuwata’s unusual, dysfunctional Japanese tea bowls in pink, blue, and yellow seem somehow connected to both Ohr’s and Laureys’s work. Perhaps it’s because of the blobs of color attached to their sides seem rebellious in some way, resembling the spirit of much of the work of the other two ceramicists.

Another artist who uses chunks of clay in his work is Sterling Ruby, an American who is well known for working in a variety of media. His series of ashtrays (seemly made of chunks of clay pressed together the way kindergarteners like to build things) are seemingly the most conventional pieces in the exhibition. But the vivid blobs of red dropped inside the pieces give them an ominous, abstract expressionist feel; the one of deep purple blue even resembles a mysterious animal footprint.

Kathy Butterly has perhaps produced the work that most closely resembles the spirit of George Ohr. Her tall caramel-colored ceramic highball glass, called Ckhaatrhlyie, folds gracefully in on itself as it melts. The smooth, bulbous surfaces of the piece fold over each other. They are so glowing and sensuous they make you want to reach out and caress them.

Gustavo Pérez’s row of 10 pieces, Secuencia de Compresión, also echoes Ohr. This array of cylindrical jars starts out with a simple tall jar on the left. As you gaze from left to right, you see that each piece collapses into a smaller version of itself until the last piece becomes an almost symmetrical, gray brick. The grouping has the same hypnotic effect as an M.C. Escher print. It certainly is in keeping with Ohr’s sensibility, except that Perez has transformed a functional vessel – the jar –into a 10-part piece of sculpture.

The two largest works of art in the show also make powerful statements. One is a giant-sized jar on a plinth by Nicole Cherubini called Nestoris II. At first glance, this piece resembles a cross between a huge Easter egg and an ancient burial jar. But the colors and the construction, with rings of glazed clay oozing out like frosting, suggest the Easter egg idea, or even wedding cake. But then you can’t miss the broken blocks at the foot of the plinth that resemble marble ruins. So perhaps the piece is a combination of both interpretations.

Finally, punctuating the exhibition with unexpected fervor comes an amazing ceramic wall called A Single Joy of Song by Betty Woodman. The dimensions are huge: 10 feet tall by 23 feet long. The background portrays a doorway and silent, empty rooms of almost Georgio de Chirico proportions, but in uncharacteristic (for de Chirico at least) happy colors. Actually, the background is not attached to the wall; it is attached to freestanding wood. In front of the wall varied shapes escape from two jars on a table, while other more colorful ceramic pieces are attached in some way to the left side of the piece and seem to flitter around almost like birds creating a joyous feeling.

Yet despite its joy, even this installation reminds one of George Ohr. The starkness of the background scene, the clean lines, the abstract birds. But instead of Ohr’s dark vision, the installation radiates joy and celebration of life. The piece is also a reminder that today ceramics has moved beyond its original functionality – to hold things or for dinnerware – and has taken its place in the world of “fine art.” It’s a different era from the one George Ohr inhabited, when he was scorned by the art establishment.

Yet Ohr might not be surprised by what’s happened to ceramics today. Despite all the rejection he received from the art world, he was confident. In fact, Clark claims that Ohr said, “One day the nation will build a temple to my genius.” And today, there is a museum dedicated to Ohr’s work right in Biloxi. It’s called the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art and was designed by architect Frank Gehry, an Ohr admirer.

But Ohr would probably be even happy to know that his influence goes far beyond that temple. His work has influenced not only many other ceramicists, but also the whole world of modern art.

Regarding George Ohr opens Tuesday and runs through April 8. Admission: $12. Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday, Thursday and Friday; 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. first Wednesday of the month; 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Closed Mondays and holidays. Call 561-392-2500, or visit www.bocamuseum.org