The world of dance is famously tough on physiques, not just in the sheer wear and tear on bones and ligaments incurred by practitioners of this most athletic of the arts, but perhaps even more so in psychological ways.

The pressure to be thin and to be in top physical shape is rarely relenting, and a new work of dance that tackles this idea head-on had its premiere Sunday afternoon in Palm Beach Gardens in a joint program presented by the O Dance and Reach Dance companies. The two troupes, one focused on ballet and classical dance (O Dance) and the other on jazz forms (Reach), have collaborated on programs for some time, and jointly run training programs for young dancers.

Sunday’s program at the Eissey Campus of Palm Beach State College was called White Hot Summer, and featured seven new works, beginning with Ballet’s Child, a six-part composition choreographed by Donna Murray that included poetry by Lani Scozzari and video by Tiffany Rhynard. The work, the first act (“Under the Surface”) of a future evening-length ballet, focused on the mental anguish of a young female dance aspirant whose dreams apparently are dashed when she is judged unworthy of joining a company.

Playing out amid relatively dark, serious poems (I will dance with no pulse) read on the soundtrack, the varied dances were primarily to contemporary classical music by composers such as Estonian minimalist Arvo Pärt (his classic Spiegel im Spiegel), Serbian percussionist Nebošja Živković, and the British “post-classical” writer Max Richter. The basic scenario, first shown on Rhynard’s documentary-style videos, involved a mother (first seen pregnant at the barre) who passes on the dream of dance to her young daughter. But the daughter finds it tough going, stepping out from her line of fellow auditionees only to be told: Lose five pounds.

Much of Murray’s setting was expressed in the vocabulary of rehearsal (Rhynard’s videos, too), with child and adult members of the all-female corps on stage practicing moves and then routines, with a nice touch at one point in which the mother (Susan Fulks) stuck out her left arm for her daughter (Dina Giustino) to use as a barre. In the third segment, titled “Class,” 10 dancers, half in white, half in black, go through a kinetic series of routines set to a powerful Živković drum piece, during which the girl finds herself unable to continue and leaves the nine other dancers to finish.

This dance had the feel of rehearsal and the sense of something exciting coming together; it fell somewhat short in its marriage to the music, which is so frenetic it needed crisper, sharper moves and much more onstage energy to make its full impact as a dance and as a persuasive element of the story, which revolves around a dancer who can’t make the grade.

Another important element of Murray’s work was the idea of support, which the girl receives from her mother but also her fellow dancers, who surround her at times, shoring her up and making her the focus. Giustino’s movements at one of these times were particularly affecting, as she slowly brought her hands down to her abdomen as if asking herself whether her body could do the things she wanted it to do. Overall, Giustino was quite good in this ballet, with an attractive, fluid ease of motion that drew the viewer’s eye and also kept her apart from the rest of the corps; the corps itself was strong, and Fulks and the young Bryn Murray also were effective in their supporting roles.

In general, this is a good idea for a ballet, and the multimedia presentation does not detract from its essential identity as a dance. It is a work in progress, and doubtless there will be things Murray wishes to change now that an audience (a relatively large one) has seen it. The dances themselves need to be tighter and more formalized so that they stand out better, thus making the whole piece integrate itself and support the scenario.

What it needs most of all is more balance. Bearing in mind that it’s the first act of a larger piece, it spends too much time on the conflicted side, with Scozzari’s well-wrought, moody poems and a slow, minimalist-oriented score foreshadowing disappointment and sadness from the first moments. It needs a separate dance, perhaps in the middle, that lets the girl be joyful: Why does she want to be a dancer at all if it’s nothing but misery and self-abasement? Although there are moments of grace and beauty for the girl, they’re cut off; she needs a dance in which everything was beautiful at the ballet, where we can get a sense of the rewards of this art form, where we can understand why it’s so painful that she can’t make it.

The second half of the program featured six short dances by a variety of choreographers including O Dance founder and Ballet Florida veteran Jerry Opdenaker and Reach Dance founder Maria Konrad. Three of them were student pieces featuring kids in the Reach/O Dance Summer Intensive Program, including a work choreographed by two students, Jazmine Colon and Emily Schwartz, whose Return, a group piece for 10 dancers, showed they already have a decent grasp of motional variety.

Opdenaker’s Triptico, set to music by the French nuevo tango group The Gotan Project, started cute, with a group of girls coming on from the left in Sugar Plum Fairy style, to be interrupted by a boy (Cameron Jackson) who interrupts them and starts to teach them other moves including dancing while joining their hands together to make big circles.

It was charming, as was July, choreographed by Jeremy Coachman, a Riviera Beach native now studying at Juilliard. Set to a song by the Canadian rapper Drake and featuring 14 girls in men’s shirts and one boy dancing in front of a lavender scrim, Coachman’s piece was fresh, inviting and clever, ending with one of the girls sliding offstage with a Bollywood-style head shake.

Konrad’s Hit the Road, a multi-movement jazz dance accompanied by classic Ray Charles recordings (including Hit the Road, Jack), featured dances for two couples and one soloist (Giustino), and then a group dance for the whole company. Konrad is a choreographer who likes to bring a sense of fun and exuberance to her work, and these pieces had a good deal of catchy, all-body moves and some engaging boy-girl courtship scenarios. The final dance, to Charles’ 1953 hit Mess Around, had the same problem that a couple other group dances had: Not nearly enough energy. If you’re going to shake your moneymaker, shake it; any film of early rock and roll dancing from this period would have been helpful for these dancers to see.

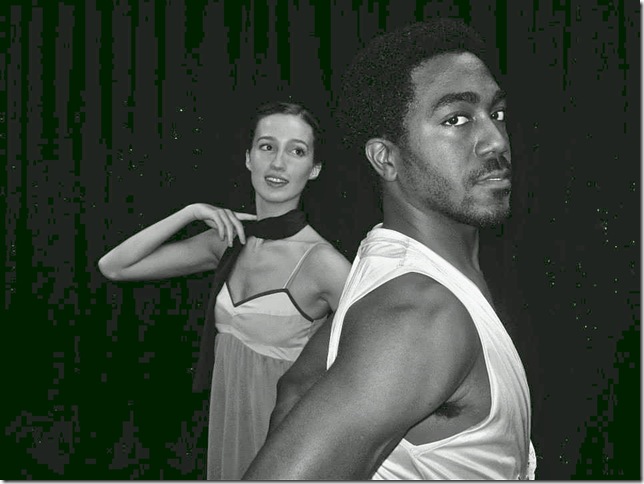

The finest dance on the program opened the second half: Opdenaker’s Othello, a précis of the Shakespeare tragedy (to my mind, the saddest of them all) for three characters — Coachman as Othello, Nicholas Garlo as Iago, and Tara Langdon as Desdemona. This was a beautiful dance, choreographed to Ennio Morricone’s score for The Mission, and one that demonstrated Opdenaker’s large and inventive dance vocabulary. This was pure classical ballet, with two gorgeous pas de deux (to the “Gabriel’s Oboe” music) for Coachman and Langdon, and a Loki-like trickster identity for the excellent Garlo, whose kinky, sneaky moves the dancer fully involved himself in, making first-rate contrast with the doomed couple.

Opdenaker knows how to match movement to music, with the fatal handkerchief, in blood-red, presented by Iago — who had carefully picked it up while Othello and his bride were otherwise engaged — with a dramatic fall back to Othello accompanied by an ominous note of bass punctuation in the music. The ending of the dance, which requires a blackout so that Othello can appear in all red with a sword to kill himself with, needs a little adjusting so that the momentum isn’t lost.

Other than that, it was lovely and moving. Best of all was Langdon, a Juilliard student who was superb as Desdemona, all liquid, all grace, all femininity, draping herself with total trust on her partner, and embodying the light-as-air otherworldliness of the prima ballerina. She is a dancer to watch, and one hopes to see her again soon, especially in things like this Othello, which in its thoroughly traditional orientation showed its audience why this art form remains so spectacularly unique.