Ongoing at the Flagler Museum is a history lesson on passion and perseverance. And unlike boring history lessons, this one is told through work songs, candid photographs and rare historic film.

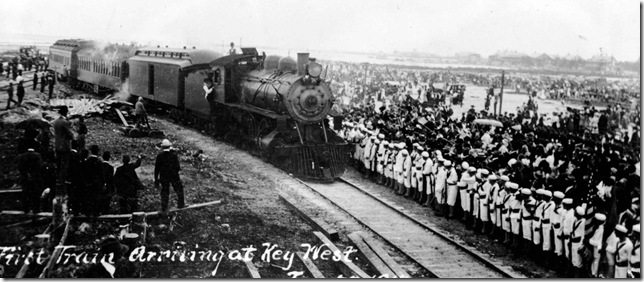

First Train to Paradise: The Railroad that Went to Sea is just the beginning of a long celebration marking the 100th anniversary of the completion of Henry M. Flagler’s most ambitious project: the Over-Sea Railroad, on Jan. 22, 1912. Unofficially, it also marks a time in history when a man with visions and dreams was able to turn them into reality, the major players being money and time. Flagler put a lot of both into this seven-year endeavor.

The fall exhibit encompasses three gallery rooms and documents the hard work, visions and ordeals that went into building this overseas railroad connection to Key West, the United States’ closest deep-water port to the Panama Canal.

The idea came to Flagler after his first visit to Florida in 1878. He saw the potential that everyone else apparently missed. A solid transportation system would mean new communities, businesses and industries as well as more tourism and a stronger agriculture. It would also mean shorter trips to Havana.

With the yellow walls and black-and-white photographs, the show may seem tedious at first glance. But that is a risk that history takes in order to tell a story accurately. It consists of mostly photographs and includes some objects and drawings.

Mangrove Swamp at Snake Creek, May 1907, features a few men facing the difficult dense terrain that the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) would have to cross many times to make the 156-mile stretch of railroad possible. Snake Creek is between Plantation Key and Windley’s Island. This is one of 44 photographs in the room featuring the land cleaning, excavating, pulling, pushing, and many other tasks.

But the biggest challenge the team faced was how to cross the major bodies of water in the Keys. We learn that a series of 42 bridges were built for this purpose. The show highlights three, the first of which resembled a Roman viaduct and became Flagler’s favorite. Known as the Long Key Viaduct, this bridge spanned 2.7 miles and later replaced the old FEC logo, as seen on a dining car menu shown in the third gallery room.

A photographic copy of a 1907 blueprint shows the massive skeleton of rods inside each concrete arch of the Long Key Viaduct: about 5,000 tons of steel were used to reinforce its long arches. The next major task was the Seven-Mile Bridge, which took four years to finish. It was followed by the bridge crossing the Bahia Honda Channel, which was only 1 mile long but 35 feet deep. A large rolling piece of scaffolding called a traveler is depicted on photograph Bahia Honda Bridge Construction. This is was one of the most unusual pieces of equipment used on the entire project. Workers needed it as they assembled the Bahia Honda Bridge’s steel trusses.

Historical audio recordings of railroad work songs give a nice touch to the second part/room of the exhibit. They include John Henry by Harold B. Hazelhurst, who, according to the description, learned this song from workers while he worked as a water boy at age 15-16 on a logging camp railroad in Central Florida. There is also Let’s Shake It, performed by novelist Zora Neale Hurston and Big Boy, Can’t You Move ’em, by “Uncle” Bradley Eberhard, who served as a singer when the men were laying tracks.

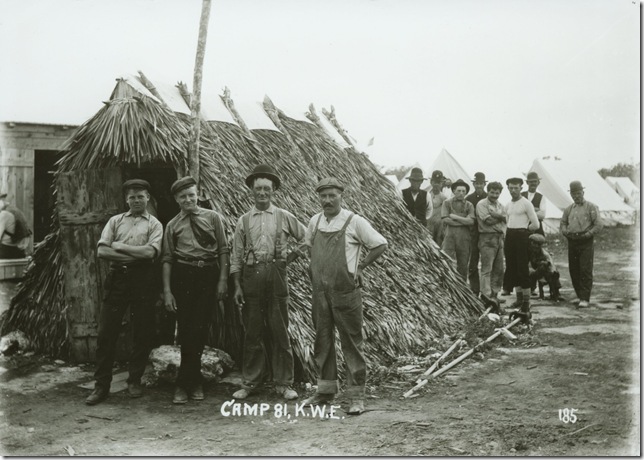

A Men Wanted poster from 1906 reads “$1.50” – as in daily salary. The wages for African-American and white workers were equal, although they slept separately. An average of 3,000 men worked on the Over-Sea Railroad at any given time. They worked six days a week and rested on Sundays.

Of the 63 photographs here, one titled Booze Boat made me smile. It features one of the private boats that offered clandestine alcohol to FEC employees. Liquor was prohibited in the living camps. This was one of the hardest policies to enforce. Booze Boat is accompanied, ironically enough, by a Safety Always lapel pin that workers presumably wore during the project.

I welcomed a series of intimate photos taken by a worker at Camp 12 which depict a makeshift barber shop and waiters and cooks posing in an outdoor kitchen. Although their clothes and hair styles are certainly from another time and contribute to making us feel all modern, the faces and expressions are not strange enough nor that distant in time, that the anxiety and uncertainty of their situation cannot reach us.

While looking at these men, standing in groups, relaxed and attentive at the same time, I wonder whatever happened to them. Did they go on to become something more than laborers? Were they missed by anyone? Did they ever doubt Flagler’s sanity over this seemingly impossible dream?

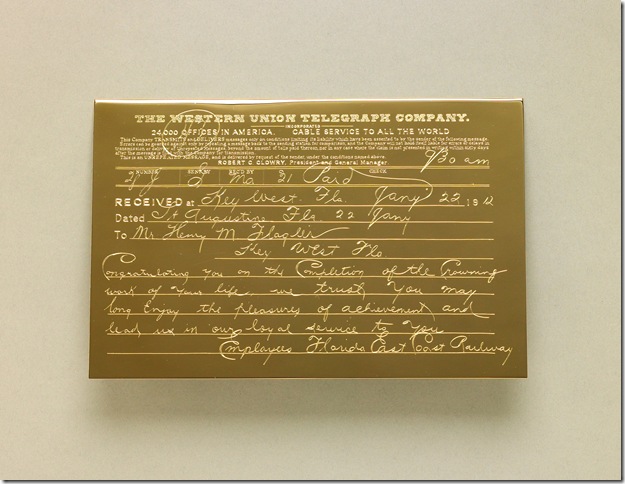

The third gallery room provides some answers as it focuses on the damages and deaths caused by unexpected hurricanes before giving us a semi-happy ending. It turns out some of these men never got to see Flagler arrive at Key West that Jan. 22 morning. The lucky ones who did presented him with a collective gift: an 18-karat gold replica of the Western Union telegram sent to him announcing the completion of the railroad. The original piece, by Tiffany & Co, was lost. Shown here is a 2006 replica produced after a six-year collaboration between the museum and Tiffany.

Flagler’s emotive letter, expressing his gratitude for this gift and for long years of hard work, is also shown here and reads: “The work I have been doing for many years has been largely prompted by a desire to help my fellow men.”

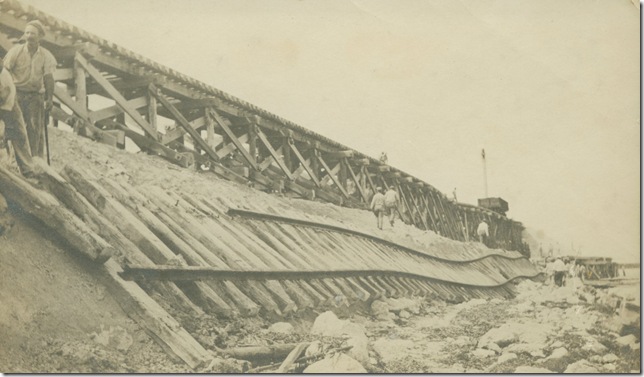

A 1935 newsreel at the end of the exhibit depicts the destruction and death caused by the Labor Day hurricane that year. The serious damage, along with new emerging ways of transportation and the Great Depression, weakened the FEC to the point of declaring bankruptcy. The roadbed and remaining bridges of the Over-Sea Railroad ended up being sold to the state of Florida, which turned the remaining railway infrastructure into the Overseas Highway to Key West.

This is a show that requires a good chunk of time, although nothing compared to the long years thousands of men and a visionary leader spent to give us the Florida we have today. It is not for those after colorful interpretations, a quick art fix or the shock factor.

But if you are one to marvel at the miracle that it is to make an imagined idea breathe in the real physical world, then this is definitely your show. Once submerged in it, you will realize it is as good as any. The best part is that it happened for real.

First Train to Paradise: The Railroad That Went to Sea runs through Jan. 8 at the Flagler Museum on Palm Beach. Regular ticket prices: Adults: $18; $10 for youth ages 13-18; $3 for children ages 6-12; and children under 6 admitted free. For more information, call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.