They say happiness is a state of mind you can command at any time and place.

The same thing can be said about beauty. We decide, in a matter of seconds, whether or not something is beautiful. In a room full of porcelain-skin ladies and velvety, satin dresses, this is not a hard decision to make.

The Society of the Four Arts has put together such a room for its ongoing exhibit: Copley, Delacroix, Dali and Others: Masterworks from the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. The show, running through March 30, features 75 of the most valuable works owned by the Canadian gallery. The artists represented include Joseph Mallord William Turner, William Hogarth, Henry Matisse and Percy Wyndham.

The collection, as well as the gallery, was a gift to the people of New Brunswick from William Maxwell Aitken, a successful Canadian businessman who made his fortune in newspaper publishing and finance in England. He is also known as Lord Beaverbrook and is the subject of a Salvador Dali painting.

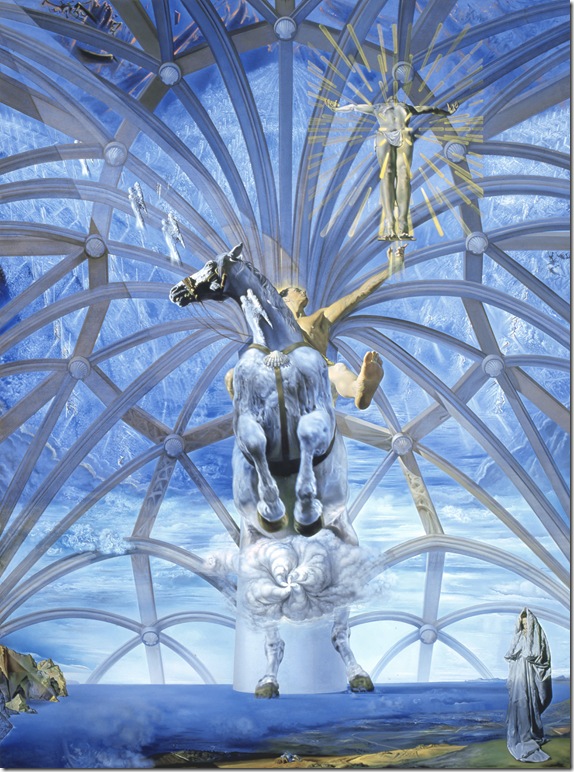

But it is another Dali that people are coming to see. His Santiago El Grande (Santiago The Great) does not have to do a lot for the crowd to go speechless. Its impressive size and skill act as a magnet, bringing us closer to the central figure of a white stallion carrying St. James toward victory.

A repetitive pattern appears all over the painting, tricking us into thinking there is a lot to see. But bigger is not necessarily better, as the artist himself wanted us to think when he compared himself to Raphael (the exact quote appears is the description next to the painting). The size does not make Santiago El Grande any more profound or significant than other paintings.

As in any other exhibit, it is up to us to find here the less-obvious places where beauty is hiding.

“We don’t see Turner in this country much at all,” said art historian Richard Frank, speaking to a crowd of visitors. He was directing their attention to the artist’s The Fountain of Indolence (1834) which is one of the first works in the exhibit. It contains the atmospheric skies and clouds typical of Turner as well as “a glow from within.”

According to Frank, the painting is about a pilgrimage, but instead of a vision of suffering and sacrifice the encircling figures here are having a great time. They appear dancing, drinking and swimming. Some are in the nude, acting as if limits or judgment of any kind were not a possibility in this place. The title, however, carries a negative connotation.

“You wouldn’t put indolent on your resume,” said Frank.

In Paul Kane’s West Coast Indian Encampment (c.1851), a group of Native Indians are seen at a fishing camp. They seem relaxed, leaning back, perhaps having a good conversation. It is a quieter picture of happiness. They do not look like persecuted people or people who have had relatives killed by strange men. Kane meant to depict a romantic notion of the “savage” before that less-romantic chapter in history: colonization.

What I like about Charles Lennox, later 4th Duke of Richmond, Duke of Lennox and of Aubigny (c. 1777) is the fact that it does so little to let us join the moment. If it were a person I would call it introverted. It is by an English portrait painter named George Romney and depicts a young boy with rosy cheeks playing with a red spaniel. The way the boy looks at the dog: calm, serious, benevolent, hints at a level of maturity greater than his age. There is something about his youth that already suggests seniority. I want to know what he is thinking, feeling.

In contrast, Scene of Woods and Water (c. 1830), by John Constable is moody, messy and brave. You could say it is very outspoken. Constable is described here as a painter who thought of landscape as more than just backdrop. Indeed, here the landscape is a state of mind. His painting depicts a dark stormy scene. To the right, an old book —presumably the Bible — appears opened as if delivering a message or maybe a punishment. A light illuminates it from above but it does not make the message any clearer. What seems obvious is that it was painted from a place of pain, sorrow and darkness.

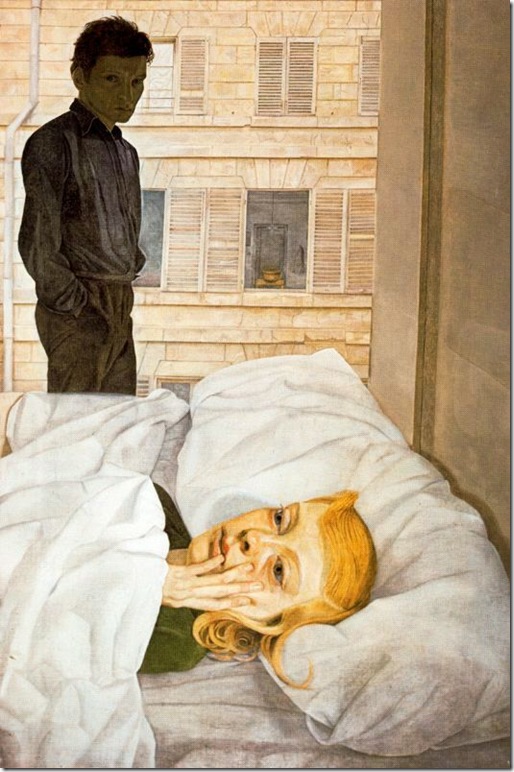

Also worthy of a look is Hotel Bedroom (1954), an early work by Lucian Freud devoid of his signature thick paint and fleshy tones. The work is rare in that it features two figures in the same space and instead of a staged pose we get a real-life event unfolding before our eyes. It does feel as if we have missed most of the narrative and have only arrived to see the end.

Next to Freud’s is The Operation: Case for Discussion (1949), by Barbara Hepworth, a pioneer of British abstract sculpture. In this drawing, all the eyes in the room are focusing on the patient and the hand gestures of the head surgeon. The thin, barely-visible pencil lines reflect the fragility of the moment.

The last piece in the exhibit to catch my attention was also the most personal. Still Life on a Table (1930) by Ben Nicholson stands up precisely for its simplicity of line, color and composition. It is a return to the flattening of the object and the purest expression of shape. A plate is a circle. A table is a square with four vertical legs, one next to the other without a hint of depth.

Nicholson also resists the temptation to add a lot of color giving us instead a view of light brown that takes over the entire canvas. It looks primitive next to more sophisticated works on display, but that is what I like about it. There is a subtle beauty in this thin-layered painting and apparently Lord Beaverbrook thought so as well.

Masterworks from the Beaverbrook Art Gallery runs through March 30 at the Esther O’Keeffe Gallery at the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $5; free for members and children 14 and under. Call 655-7226 for more information.