By Robert Croan

Most classical string quintets add a second viola to the standard string quartet combination of two violins, viola and cello. Several repertory works by Mozart and Brahms, for example, employ this combination.

Less common are quintets with a cello as the fifth instrument, with the notable exception of a large number by Boccherini (remember the piece played in the film The Ladykillers) and a single stunning masterpiece by Schubert, his so-called “Cello Quintet” (in C major, D. 956)

Performing on the Chameleon Chamber Music Series on Sunday in Fort Lauderdale’s Josephine S. Leiser Opera Center, the Amernet String Quartet, ensemble-in-residence at Florida International University, uncovered not one but two rarely played quintets with two cellos: one by English composer Dame Ethel Smyth, the other by the German Walter Braunfels. These players – violinists Misha Vitenson and Marcia Littley, violist Michael Klotz and cellist Jason Calloway — were joined in the quintets by the series’ founder, Iris Van Eck, a first-rate cellist and one of this city’s busiest and most visible classical musicians. It was an afternoon of splendid music-making, and a glimpse into an aspect of chamber music repertory that is all but unknown, even to professional string players.

The guest quartet warmed up on three short and pleasant Paysages, musical sketches by Swiss composer Ernest Bloch, each depicting a diverse travel destination: Alaska, the Swiss Alps (Bloch’s homeland) and Tonga. Then on to the meat of the afternoon’s repertory.

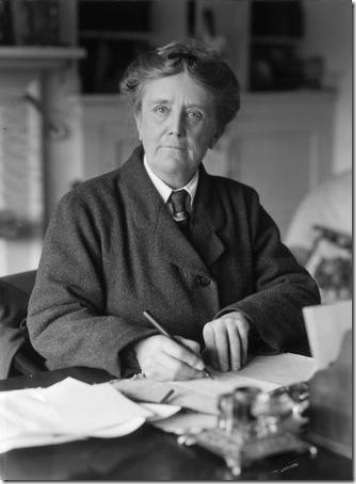

The date coincided with International Women’s Day, but Smyth’s lively, elegant score needed no excuses for its composer’s gender. It’s a delightful, well-crafted piece in the grand tradition, and the present rendition did justice to every last detail.

Smyth’s story is inspiring and sad. Born in London in 1858, she overcame her father’s objections to a career in music, and studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, where she met, among others, Dvořák, Grieg, Tchaikovsky and Brahms. Despite prejudice against women composers in her lifetime, she produced a large musical output of instrumental works and operas, including Der Wald, to this day the only opera by a woman composer produced by the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Early deafness, however, cut short her musical activities, and she turned to writing literature. She was also bisexual, joining the women’s suffrage movement when she fell in love with suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, and composing an anthem for the movement. Late in life, she fell in love with author Virginia Woolf (who did not reciprocate).

The Brahmsian sonorities of Smyth’s String Quintet, Op. 1 (published in 1884 but not her first composition), was a good vehicle for the Amernet ensemble’s full-bodied resonance and buoyant spontaneity. The piece has an individual profile, though it is in no way revolutionary.

Sunday’s players seemed to relish the perky dotted rhythms of the opening movement, as well as the piquant pizzicato beat of the Andantino that followed. There was a streak of humor in this spunky woman who defied all odds to follow her aspirations, and the performers maintained momentum, intense but never heavy, through the ebullient Scherzo and animated finale.

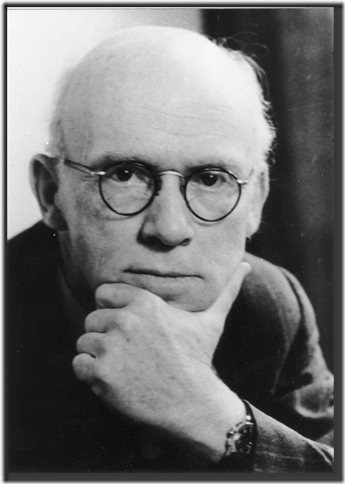

The real-life story of Braunfels (1882-1954) was filled with travails of a different sort than Smyth’s. After a promising start, his career was squashed by the Nazis for his being half-Jewish. Because it was his father who was Jewish and he was not a practicing Jew, however, he was sentenced to “internal exile” rather than the camps. He spent the war years in safety, but his music was banned as entartete (degenerate). After the war, Braunfels became a successful teacher, but his compositions never regained the popularity or success he had once expected and hoped for.

Braunfels composed his Quintet in F Minor (Op. 63) in 1944, a time when he had little hope of seeing his music performed. It is a somber work of much gravitas, thickly scored, unrelentingly harsh in its opening movement, which reflects the mood of the times. The performers were undaunted in meeting the score’s enormous technical demands, imparting dark resonance and austere demeanor while maintaining a rich-hued splendor that almost but not quite masked the music’s complexities.

The Adagio movement comprised varying dialogues among the five instruments, each emitting wordless sentences that might be interpreted in this very expressive delivery, as denoting hope or despair. The Scherzo was lively and incisive, but not at all happy. Only in the final movement did the composer allow in some rays of light — a folk-like dance tune alternating with lyric melodies beautifully played by violist Klotz — which led to a conclusion in which the performers’ energy never flagged.