By Clare Shore

(Editor’s note: The publication of this review was delayed by technical difficulties.)

To delight or not to delight? Surely the latter is out of the question, and as for the former, it’s exactly what Seraphic Fire did in its season-closing concert of music inspired by, or set to, the work of William Shakespeare.

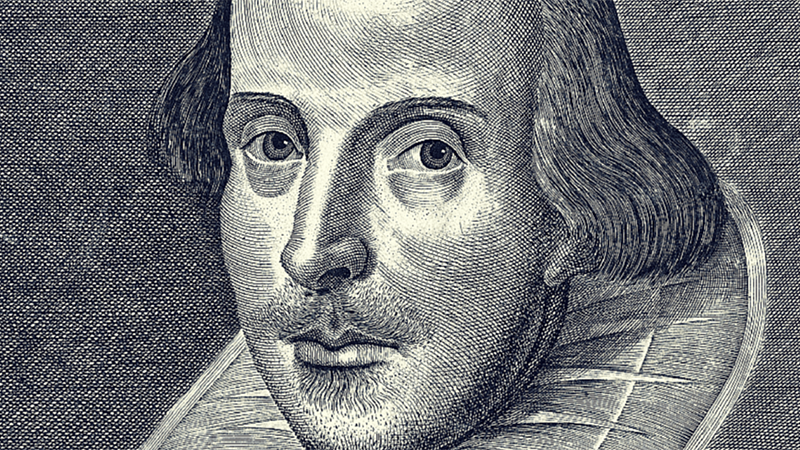

At the May 12 concert at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale, tenor Brad Diamond, who frequently appears with the Miami-based concert choir, gave an illuminating pre-concert talk. Diamond said he was no expert in the history of the Renaissance, but he was able to paint an apt picture of life during that period, and of the musical figures who were contemporaries of William Shakespeare, who was born in 1564. He also pointed out the importance of music, directly or indirectly, in Shakespeare’s works.

James Bass, associate conductor of Seraphic Fire, led the proceedings with warmth and grace. His unassuming, easy manner is refreshing but belies his skill as a conductor and communicator. In his introduction to the program, he teasingly warned the audience of the surprises that lay ahead and to be prepared for anything.

The most notable surprise began at the end of the program’s second selection, at which time a woman from the audience called out loudly and proceeded to walk to the stage and deliver a dramatic monologue of one of Lady Percy’s speeches from Henry IV, Part 2. This was actress Siobhan Doherty, clad in a three-cornered hat, who appeared several times during the evening to offer speeches from plays including As You Like It, Hamlet and The Tempest.

Several of the works on the May 12 program were credited to anonymous composers, the first of which was “Ah, Robin,” from Twelfth Night (though this tune is usually attributed to William Cornysh, who served at the court of Henry VIII). It was the second selection on the program, a brief three-voice madrigal sung charmingly by bass Thomas McCargar, baritone John Buffett, and tenor Patrick Muehleise.

The second anonymous song, “Robin Is to the Greenwood Gone,” was delivered sweetly by soprano Brenna Wells between sets by Thomas Morley and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Following the Vaughan Williams set was the third song, “Take, O Take Those Lips Away,” sung very expressively by alto Emily Marvosh, whose affect vividly echoed the text.

The fourth anonymous song, “Come Away, Death,” was beautifully offered by baritone John Buffett, while the fifth, “Fie on Sinful Fantasy,” was sung by soprano Chelsea Helm with an appropriately feisty expressive vibrato. Diamond initiated the final anonymous selection, “Three Merry Men,” and was quickly joined by bass Charles W. Evans and tenor Stephen Soph; the three men hammed up the brief, humorous excerpt, a crowd favorite.

Six living composers’ works were represented on the program. The evening’s opening selection, “Music to Hear,” set to Sonnet 8 by the British composer Mike Sheppard (b. 1958), is an easy work to listen to; its tertian harmonies are first presented with single-line melody in the soprano line and accompanying ostinati consisting of the word “music” in the alto line (in augmentation in the bass), followed by a freer section with melody moving from voice to voice, returning to the ostinato from the opening and culminating in a homophonic section with additive harmonies building to a forte climax with pitches fanning out from mid-range to low and high, then decreasing the dynamics phrase by phrase to the pianissimo ending.

Four songs by New Yorker Matthew Harris (b. 1956), from his six books of Shakespeare Songs, written from 1989 to 2009, also were featured. The set makes for easy listening; each song has a key signature; chromaticism rarely is found in them. Harris is adept at setting works for the voice, but his constant use here of the mid-register results in a lulling sameness. Bass thankfully allowed some leeway in interpretation which added some spice. For example, Patrick Muehleise enhanced the tenor solo in “O Mistress Mine” by presenting it in a pop style with scooping.

The opening of Harris’ “I Shall No More to Sea” was reminiscent of Sacred Harp-style singing with its open fifths, but went straight into a more traditional harmonization. Its ending was quite puzzling in that it didn’t resolve normally; perhaps when followed by the song which actually follows it in Book V the two meld well harmonically. The piece de resistance of the set was the final selection, “It Was a Lover and His Lass.”

Preceding the song, during her monologue as Titania from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, actress Doherty slinked her way up to baritone Buffett (actually her husband) and appeared to stroke his collar; in actuality she was very slowly beginning to pull a long white scarf/shawl from beneath his jacket, reciting all the while. This set the tone for the jaunty musical performance which followed. Bass’s interpretation further brightened the performance; the delivery of the “hey, ho” punctuating ostinati in the tenor and bass lines was enhanced by accents on each of the words with immediate diminuendo.

Swedish composer Nils Lindberg’s (b. 1933) setting of “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” (Sonnet 18), is lush with close harmonies, sprinkled with occasional dissonance and filled with word painting, especially effective at the setting of sorrowful words concerning death toward the end, and the final two lines of text, which fairly blossom with brightness: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see/ So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.” The final chord, a major triad with major seventh. adds to the brilliance.

“When He Shall Die,” by Pennsylvania composer Steven Sametz (b. 1954), is built on attractive harmonies, but ones that demanded perfect intonation; this performance fell short of that mark at times. The text was presented almost exclusively in syllabic form with little or no melisma. Rhythmic variety was lacking as well. The text fairly sparkles and calls for like musical setting, but the music didn’t meet that challenge.

Benjamin Montgomery (b. 1991), a DMA student in the composition department at the University of Miami, is currently a composition apprentice with Seraphic Fire. Montgomery’s work, “To Hear With Eyes,” was premiered on this program, immediately following the Sametz work. It is a substantial piece in which Montgomery has employed many different techniques such as imitative sections and snippets, non-harmonic tones and their resolutions, and additive harmonies. all of which are tasteful and faithful to the text.

The two-line contrasting syllabic, repetitive “Who plead for love and look for recompense more than that tongue that more hath more express’d,” four lines from the end of the text, builds beautifully to the song’s climax. Montgomery is most assuredly a composer to watch out for.

The other contemporary composer, Finland’s Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (b. 1963), was represented by two of his Four Shakespeare Songs. The introduction to “Lullaby” consists of descending, sliding chromatic harmonies which settle into an ostinato on “Lulla, lulla, lullaby” underneath a teasingly macabre melodic line that chides in an appropriately accented, bouncy line for spotted snakes, thorny hedgehogs, newts and blind worms not to come near “our lovely lady.” It is an altogether charming song, one which might have been fitting in an Addams Family episode.

The other song, “Double, Double Toil and Trouble,” from Macbeth, features those words as an ostinato underneath the rest of the text. The first half of the second stanza was sung with a nasal quality in ascending sliding chromatic harmonies; the remainder of its text was whispered against sustained humming with crescendo in both parts to whinily sung descending chromatic harmonies on the familiar final two lines. Segueing into the final strophe, the music soon takes on the harmonies of barbershop quartet. Each line ascends above the previous, repeating with crescendo the familiar final two lines a few times before singing the last three lines of the song, stomping feet on the floor once after the final line, “Open, locks, whoever knocks!”

Of the deceased, non-anonymous composers on the program, the single song by William Byrd (1538-1623), “Come Woeful Orpheus,” and the set of three songs by Thomas Morley (1557-1602), “April Is in My Mistress’s Face,” “Nolo mortem peccatoris,” and “Sing We and Chant It” are rather typical works of the Renaissance period. However, the Byrd selection is secular, which, as conductor Bass pointed out, is unusual for this Catholic composer. The singers didn’t seem to click well with the piece; there was little discernible diction and intonation proved a problem. The altos, in particular, failed to blend well and the timbre of one or two of the section’s voices wasn’t pleasant.

The four Morley songs fared better; however, balance was less than ideal in the second song. “Nolo mortem peccatoris” was of note for its use of alternating Latin and English languages; the altos again had issues with timbre and volume. The final Morley song was a delightful, spirited tune which was very well sung with good balance and blend and superbly communicated by Bass.

Perhaps the most surprising work of the program was the set by Ralph Vaughan Williams, Three Shakespeare Songs. Known primarily for his myriad lovely modal works of the English pastoral school, with certain exceptions such as the Five Mystical Songs that explore a more lushly chromatic harmonic scheme, Vaughan Williams in the Shakespeare songs employs very challenging dissonances and chromatic harmonies to wonderful effect, beginning with “Full Fathom Five.”

“The Cloud-Capp’d Towers” explores extreme registers, first high, then low, with shifting, sliding harmonies, unusual modulations, and wonderful word painting. “Over Hill, Over Dale” begins with repeated figures in minor seconds and ends the final substantial stanza with very rapid speaking; the song is over in a flash.

All Saints is a wonderful venue that lends itself to the production of a round, blended musical sound; unfortunately for vocal groups, this velvety sound is at the sacrifice of clarity of diction. Thankfully the text for each selection was printed in the program or the listener would have come away with only partial enjoyment of the selections. Among standouts for their crisp diction especially in small ensemble selections were basses McCargar and Buffett, and tenor Muehleise.

The music and the performances in Shakespeare: Music and the Bard were overall stellar; the atmosphere as set by Bass was cordial and relaxed; the added feature of Shakespearean monologues delivered by a professional actress was the icing on the cake.