In an effort to acknowledge their origins, it has become increasingly customary for dance companies that have been around for a long time to continue to present repertory that spans the years since their founding. On Feb. 17, Ailey II made its first appearance as part of the popular Modern Dance Series at the Duncan Theatre in Lake Worth, presenting something a little old, something not so old and something almost new.

As with most of the dance companies which are trying to preserve the legacy of their founders, the first part of the program paid homage to the old works and the newest works fell into the second half of the program, and that was where things really start to take off.

The merits of presenting something old first on the program were tested with the brief excerpt from Alvin Ailey’s The Lark Ascending (1972), which was a world premiere for the off-shoot Ailey company. Though nicely danced by Meagan King and Andrew Bryant, the short, 50-year-old duet did not hold up that well in this 2023 program and posed the question — does it do justice to these historic works to present them on the same program as the works of today’s choreographers? Dance — like all things — has changed so much in half a century.

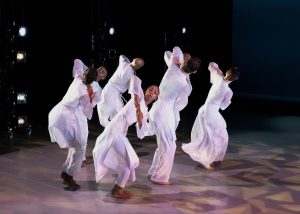

The next work presented was Robert Battle’s Alleluia (2002), another world premiere for Ailey II that paid homage to Ailey’s iconic spiritual work Revelations, choreographed in 1960. Battle, who is now artistic director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, tapped into the same Baptist church roots that inspired Ailey’s spiritual work. The seven dancers wore bright white costumes, designed by Mia McSwain, that resembled ecclesiastical garb, as they jubilantly filled the stage with their gaze lifted and arms raised upwards in reverie.

Battle made an interesting choice in music using the Baroque composers Scarlatti, Handel and Bach to set his rhythmic and grounded choreography. Nestled in the middle of the work, amid the foot stomping and hand gestures of the small ensemble, was the striking solo of Tamia Strickland, who made a strong mark both artistically and visually dressed in her rich dark red dress. Jaryd Farcon followed, showing a clean and concise movement quality in his bare-chested solo.

The third world premiere of the evening was mediAcation, choreographed in 2002 by former Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater dancer Elizabeth Roxas-Dobrish. With music by various artists including Nicholas Britell and Alberto Iglesias, this 19-minute work featured three couples and a lot of rope. In the talk-back after the performance, we were informed that the theme of this dance dealt with the pressures of social media, hence the ropes — I guess. It seems that the choreographer aimed to capture the angst of a social media construct while also revealing the intense need to connect.

I didn’t pick up on this theme at all and even with this hindsight, I didn’t see much of a relationship between the dancers and the rope other than at the beginning when they were tied up in it. It just seemed like a distracting and unnecessary prop that too often pulled the focus away from the duets. This was particularly awkward when the third duet started and the previous couple had to gather up the rope so that the next duo could dance.

The standout duet was the final couple dressed in blue — Kali Marie Oliver and Andrew Bryant. Dancing to a slower score, there was a natural familiarity and relatable connection between them. There was also a beautiful flow to their partnering with its interesting lifts.

Like a rocket launching, the last piece on the program blew all the other pieces away. It was trademark William Forsythe — intense, compelling and masterfully constructed — even though what we saw was just an excerpt from his dynamic full-length work Enemy in the Figure, created in 1989 for his company Ballet Frankfurt. This 18-minute section taken from the middle of the work was something to behold. It was sheer driving energy. It was so “today” that it was hard to believe that it was created 34 years ago.

Forsythe is known for breaking boundaries and this work, choreographed to the driving electronic score of longtime collaborator Thom Willem, was a tremendous vehicle to show the talents of the almost-all-new company members of Ailey II. The young dancers pulled out all the stops, letting it rip and completely owning the sleek movement style that gave each dancer room to improvise in the fast-paced choreography, much like a musician improvising in a jazz ensemble.

Besides creating the riveting choreography, Forsythe also did the original lighting (recreated by Ethan Saiewitz), costume design and in the full version, he also conceived the set designs that heightened the definition between the space and light. Even though this excerpt was presented without the sets, Forsythe’s strong sense of crafting space, time and light was very evident.

Although the beginning was stark and dark, the all-black costumes that the dancers wore immediately made an impression. The pant legs were completely fringed like a flapper’s Roaring Twenties dress and flared out as the dancers sliced through space. There was something mythical about the look of the costume like a centaur lost in an urban nightscape. The dancers were fearless each bursting with a self-contained energy.

Rachel Yoo was a fast, furious and impactful mover. The bold lighting cues were executed in a split second and to a precise note in the score. Alfred L. Jordon II was a standout, looking like a mini-tornado as he whipped off multiple turns, proved to be an excellent partner when he later paired with Oliver in an intricate duet.

As the excerpt progressed, bare legs and arms started to appear bathed in strong amber sidelights. Muscles rippled and as the mood evolved. The sense of urgency subsided as the tall and elegant Strickland, with her sculpted legs glowing, danced a solo to sound of fading drums.

Spencer Everett, adding a fully fringed jacket to his fringed pants, lit a trail of energy across the stage with his red hair blazing in the monotone setting.

I particularly enjoyed a well-placed moment of calm in choreography where a quartet of women, one by one, introduced a repeating and mesmerizing simple sliding step in the back and off to the side that managed to ground and surround — but not distract — the transition from Strickland’s solo to the next solo, where King was caught quietly dancing in a cool white circle of light.

For me the legacy evident in Ailey II doesn’t come as much from the historic dances in the repertory as it does from all the creatives that have been touched by Alvin Ailey’s artistic vision – the dancers themselves, the teachers at the Ailey School who trained them, and the choreographers and directors that returned to the fold to give back. They are keeping his vision alive within themselves and sharing it with their audiences no matter what dances they are dancing.