Why is it that genre writers, just when they are about to step onto a wider stage of literature, tend to lose heart – or nerve?

I first noticed this in 1998 when Stephen King, after almost a decade of increasing critical acceptance, retreated to the comforts of Bag of Bones, an overlong, overstuffed supernatural thriller of the kind that made him famous earlier in his career. Perhaps spooked by reviews that took him seriously (from the likes of The New York Times), King abandoned, if only temporarily, the more rigorous pleasures of novels such as Misery, Gerald’s Game and Dolores Claiborne.

Now China Miéville seems to be following a similar pattern. Last year Miéville, already a popular figure in the neo-horror genre sometimes known as “weird fiction,” gained new readers and critical acclaim with the spare but deeply inventive fantasy-detective novel, The City and the City. Some critics named it to their year’s best list and at least one (uh, that would be me) said it was the top novel of the year.

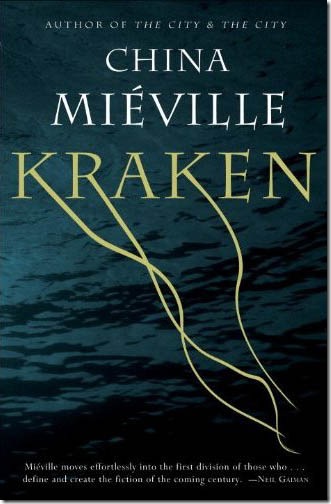

Miéville’s follow-up to that breakthrough, alas, is an exercise in apocalyptic excess titled Kraken (yes, “kraken” as in Liam Neeson thundering, “Release the Kraken!” in Clash of the Titans). It’s a huge disappointment, not only because it signals an aesthetic retreat from the high-wire performance of The City and the City, but also because it’s only so-so, even on its own weird fictional terms.

The ponderously convoluted plot starts when a kraken – a rare giant squid – disappears from the Natural History Museum in London, along with its tank of formalin. This is an impossible crime, of course, requiring dozens of men to carry out, and besides, the huge tank would not fit through any of the available doorways.

Genre geeks (or at least those unfamiliar with the kitchen-sink aesthetic of weird fiction) will think they know what kind of story this is when the police send the Fundamentalist and Sect-Related Crime (FARC) Unit to investigate. We’re well familiar with occult cops via The X-Files, Torchwood, Fringe, etc., and we’re primed to admire their interaction and heroics.

Miéville has bigger, er, calamari, to fry, and the FARC squad is soon revealed as unequal to the present apocalyptic crisis. Billy Harrow, the squid’s young curator, doesn’t trust them, casting his lot instead with a cult of kraken worshippers who, to his discomfort, regard him as a prophet. The kraken cult proves impotent as well, and soon Billy is careening around London in the company of Dane, a stupendously competent kraken-cult apostate, trying to recover the missing squid and thereby avert a Fiery End of Everything.

While I’m all for subverting genre expectation – surprise is the soul of great horror, not to mention comedy – Miéville packs so many ideas, characters, and spoofs into this trunk that the fun goes out of the thing. One minute it’s a parody of Star Trek, the next it’s a labor comedy, with magical familiars going on strike against their oppressive masters, and the next it’s a religious thriller. And it’s always a Lovecraft spoof. No matter how clever Miéville is (and he is), this is not storytelling, it’s riffing.

Much can be found to admire in Kraken. Goss and Subby, an ageless old man and an idiot boy, make for a supernatural team of hit men fit to scare the small child in all of us. Likewise the Tattoo, an occult gang leader turned into, well, a tattoo by a rival – not that this hinders him much in the administration of his underworld business interests.

Kraken also is admirable for taking religion seriously – or, if not religion, then at least the faith of those who believe. Of course, it turns out that all religions are equally true, which, in a tiresomely predictable bit of triumphant secularism, means they cancel each other into mutual irrelevancy. This is nicely illustrated when various cults find they have scheduled their competing apocalypses on the same date, one of Miéville’s more successful stabs at humor.

Overall, though, Kraken is just too, too much. On top of everything else, it’s needlessly long. This book would have been significantly more effective with 200 pages cut out. It has too many passages in which the narrator explains what’s just been made abundantly clear in an exchange of dialogue. Wati, a spirit who can inhabit statues and figurines, spends much of the story in a Capt. Kirk action toy. He’s an important character – yet we do not need the detailed account of how he made his way back from the afterlife to become the leader of the magical helpers’ union.

A little restraint might be hoped for next time out, the kind Miéville used to craft the superior The City and the City. Does he know his Lovecraft? Indeed he does. But the way Miéville includes every Lovecraftian idea he’s ever had robs the Cthulu tropes of all their uncanniness, leaving them about as scaresome as a pickled specimen in a museum.

Miéville seems to have written Kraken in that café where Clive Barker, Neil Gaiman and Douglas Adams take tea. His debt to each one is plain as a nametag or a numbered jersey. While Miéville is as gifted as these esteemed Brit fantasists, this novel, alas, is neither as charming as Gaiman, as funny as Adams, nor yet as sexy (or terrifying) as Barker. I’ve seldom opened a book with as much anticipation, after the satisfactions of The City and the City, nor been so keenly disappointed.

Kraken, by China Miéville; Ballantine Books; 509 pp.; $26.