The first time I came across his name was a couple of years ago at the Boca Museum of Art. I was there to do a story, in which I ended up mentioning this one painting I had really liked.

But I did not know then whose work it was, who was this Matta guy other that a Chilean artist whose name sounded like plant in Spanish. Ironically, this is what Roberto Matta tried hard to avoid: being linked to a particular place, language and time.

The compact but meaningful exhibit running now through May 18 at the Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens aims for what I failed to recognize that day: Matta’s work is a cosmic experience that penetrates all ages, backgrounds and genders leaving one with nothing to hide behind.

And yet, one cannot find a book dedicated solely to him in the city library. My own books mention Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock and others who came to influence and work with Matta, but still leave him out.

Then there is the Ann Norton exhibit, which consists of 10 works taking us through surrealist drawings from Les Escrobates series (1970) to abstract oils combining exploding lights with mechanical structures. None of them would have been created had the trained architect not met Federico Garcia Lorca and Salvador Dali and joined the Surrealists in 1937.

In the first room to the left hang the Escrobates pieces, which feature freely drawn playful figures in warm tones. The curvy lines and relaxing poses lend the scenes a happy atmosphere and a touch of eroticism. In one of the drawings a figure even appears to be holding male genitalia.

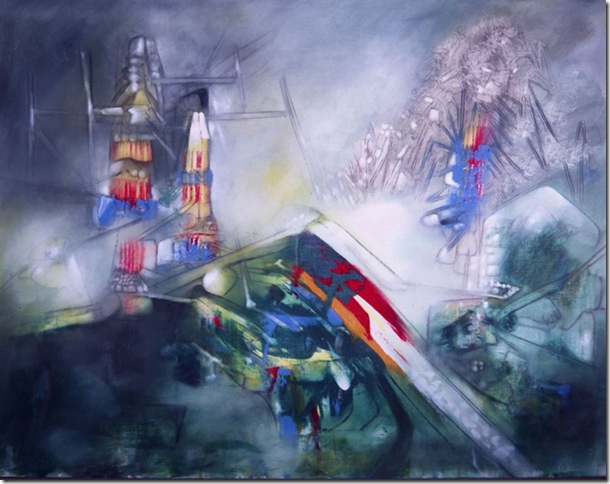

Un mot d’amour (1967-68) spreads horizontally on the south wall of the second room. The eyes travel from left to right chasing the bright yellows smartly distributed along the canvas. Shapes resembling old airplanes or glass panels appear suspended in space. It is here that I recognize the green hue from that first painting of his I ever saw. This green I have come to associate, perhaps unfairly, with Matta, is also present in a 1959 untitled work later in the show. This time, instead of alien beings, I found abstraction paired with machine-like shapes erupting from the ground.

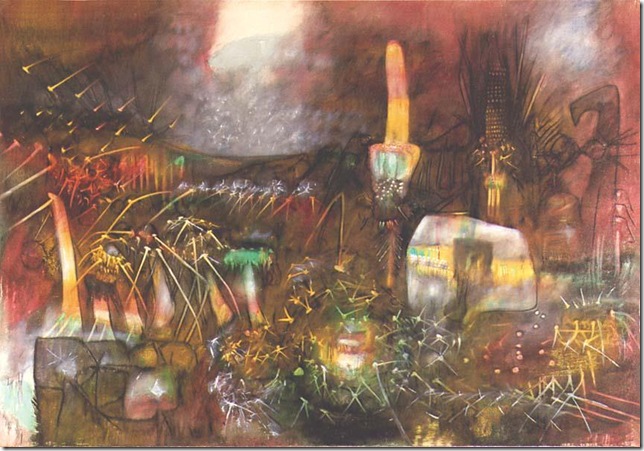

The third gallery room houses the largest canvases, among which one finds a 1954 piece named Todos Juntos en la Tierra. It means All Together on Earth and features sparks of neon colors and explosions of light. While the top half of the canvas is serene, less busy and lets one think, the bottom half illuminates the space like an amusement park and orders one to react.

This particular piece serves as a reminder of something Matta once said referring to painting:

“If this light gun could bombard the mind from the inside and the outside, spreading out the emotional structure and illuminating it totally, we could begin to see how, when, and where emotions act and react; we could grasp reality … the real is made of oscillations, waves, beams; a world is a nexus of vibrations.”

Opposite from Juntos en la Tierra, hangs L’Unifre 209 (c.1950-59). A figure I sense to be female appears to be covering her face. The gesture suggests humiliation and shame. Matta allows his lines to flow and curve for the most part. There are also sharp edges. As other pieces here, the spatial background is washed in whites and grays and outlines appear drawn in bold.

Compare this to another untitled painting from 1959 featuring the white-gray palette. It includes orderly strokes of magenta and cobalt blue. The mechanical shape on the left resembles a spaceship shooting colorful missiles. This picture speaks of movement, speed and energy and has an industrial quality to it.

In the room leading to the gardens, one finds a curious pastel piece that also embodies energy. It features a musician becoming one with his violin. The physicality involved in this activity is emphasized by the presence of not one but three bows and extra hands holding them. The musician almost turns into some kind of monster or beast who arches and contours his body to satisfy the instrument or, perhaps, the musical score. It is titled Moto Perpetuo (1979).

It takes these few paintings to boost one’s interest in Matta, but the exhibit’s not-so-secret motive is to demand more room (in a major museum preferably) for an artist who was born in 1911 but seems could have been born anytime and anywhere. He is that relevant.

I am not saying you must definitely feel something looking at his works. If you feel nothing, that is fine, but you might want to check your pulse. One cannot hide behind the usual excuses for not getting him. One could not say Matta is too European, too abstract, too surrealist or too anything.

In his paintings, he referenced many of the outside influences and styles he came across, and left enough of them out to let his own style breathe. How selfish of him, you say? For an artist, that is almost a compliment.

The Surrealist Roberto Matta is on view at the Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens through May 18. The galleries are open from Wednesday through Sunday 10 .m. to 4 p.m. Admission: adults, $10; seniors, $8. Call 561-832-5328 or visit www.ansg.org.