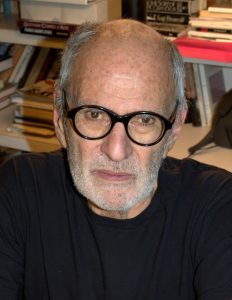

Immersed, as we all currently are, in the scourge of coronavirus, the AIDS epidemic seems like such a distant memory. But nothing brings its horrors back with a jolt quite like the death Wednesday of activist-playwright Larry Kramer at the age of 84.

The co-founder of the AIDS service organization Gay Men’s Health Crisis and founder of the more politically militant ACT UP, Kramer was the conscience of the gay community for the past 30 years, an angry man who channeled his anger into forcing government and media to focus their attention on this deadly disease.

And for the public, he chronicled the history of AIDS and his activism in the play, T he Normal Heart, first off-Broadway in 1985, then in a Tony Award-winning Broadway revival in 2011 and, finally, in an HBO film adaptation in 2015.

In the early days of AIDS, Kramer was a self-designated “pain in the ass,” notably to New York Mayor Ed Koch and to The New York Times, neither of which he felt were paying sufficient attention to the highly contagious disease. One wonders how Kramer would be railing against our current president these days if he had been well enough. And reportedly, Kramer was at work on a play about the COVID-19 pandemic when he succumbed to pneumonia, a vestige of his own long battle with AIDS.

I interviewed Kramer once, back in early 1986, in his Washington Square apartment, as The Normal Heart was beginning to spread out to regional theaters across the country. Articulate and surprisingly soft-spoken, he readily accepted the general criticism of his play that it was too caustic for its own good. “Maybe it is too angry. I don’t know,” he said to me. “That’s what it is and that’s what the play is about – an angry man.”

Kramer was the model for that angry man, the slightly fictional Ned Weeks, the thorn in the side of authority. And Kramer conceded that he was often too angry for the organizations that he began, both of which eventually were compelled to kick him out of their ranks.

As he said at the time, “Like everyone who takes a strong stance on anything, I have people who support me and people who don’t. Everything I’ve ever done has been going against the stream. It’s as simple as that.”

Even when not overly political, Kramer pushed boundaries and raised hackles. In 1969, he produced and adapted D.H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love into a film that earned him an Oscar nomination for his screenplay. But at the time, much of the attention went to a full-frontal nude wrestling scene between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed. A decade later, he was angering the gay community with a tell-all novel of the New York homosexual scene, called Faggots.

The last time I saw Kramer was at a press preview of the Normal Heart revival. As the audience exited the theater, there on the sidewalk was a frail old man, passing out pamphlets on the continued need to “act up,” to keep at the fight against AIDS. It was Kramer, still vigilant, still doing whatever it took to spread the word about the cause he committed his life to. And that is the way I choose to remember Larry Kramer.