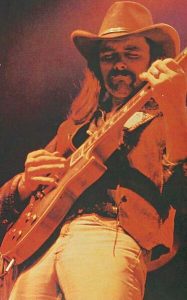

It’s safe to say that no one from West Palm Beach ever achieved more musical sales, awards, touring miles and accolades than singer, songwriter and guitarist Forrest Richard “Dickey” Betts. Especially someone from the city’s Westgate section, that small tract of diminutive homes and businesses just south of Okeechobee Boulevard between Congress Avenue and Military Trail.

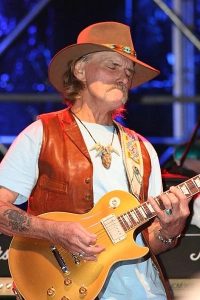

Betts lived most of his life in Florida, including growing up in Bradenton. He died on April 18 at his home in Osprey, near Sarasota, of cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at age 80. Surrounded by his wife and children, he’d previously suffered a mild stroke and a head injury from a fall, both in 2018, that canceled area concert dates and required surgery to relieve swelling on his brain.

Name-dropped in his teenaged band The Jokers (by singing guitarist Rick Derringer in his 1973 hit “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo”) and by his own name (by the Charlie Daniels Band in its 1974 hit “The South’s Gonna Do It Again”), Betts would also work with the groups Second Coming, Great Southern, and his own self-titled act.

Yet there’s one band moniker with which Betts’ name will remain practically synonymous. He was a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band, the Macon, Ga.-spawned act that featured his vocals, guitar and compositions — notably jazz-tinged instrumentals — for the bulk of the band’s iconic 1969-2014 run.

“I never studied jazz,” Betts told me in a 2018 interview. “I’ve certainly listened to it, but I don’t write songs with any conscious decision of including it as an influence. It just happens to get in there somehow.”

The Allmans were also supplied with musicians from Betts’ other bands. Founding bassist Berry Oakley (1948-1972) had worked with him in Second Coming; guitarist Dan Toler (1948-2013) and bassist David “Rook” Goldflies entered from Great Southern in 1979, and singing guitarist Warren Haynes joined out of Betts’ self-titled group in 1989.

Southern guitar hero Duane Allman (1946-1971), singing keyboardist and brother Gregg Allman (1947-2017), and double-drummers Butch Trucks (1947-2017) and Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson rounded out the Allmans’ original lineup with Betts and Oakley. The group eventually rehearsed at Oakley’s residence in Macon, which is now a recommended tourist destination called The Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House (thebighousemuseum.com).

“It’s unbelievable that myself and Jaimoe are the only two left,” Betts said during the same interview, which preceded his stroke, head injury, and concert cancellations.

The Allman Brothers Band (1969) was recorded at Atlantic Studios in New York City, and featured mostly bluesy compositions by the soulful-singing Gregg Allman, including the classics “It’s Not My Cross To Bear,” “Dreams,” and “Whipping Post.” But the group’s 1970 sophomore album, Idlewild South, started a long association with producer Tom Dowd (1925-2002), often at Criteria Studios in Miami, and launched Betts as a viable songwriting alternative to the band’s namesake vocalist. That album featured Betts’ gospel-tinged chant “Revival” and the instrumental “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.” Its title was inspired by a romantic encounter Betts had at Rose Hill Cemetery across town in Macon (where both Allman brothers and Oakley are also now interred).

The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East, the group’s 1971 double-live album, catapulted it to stardom that summer — largely because of the stinging twin-guitar heroics of Betts and Duane Allman on extended versions of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” and “Whipping Post.” Then a series of tragedies struck that would’ve ended lesser bands. The first was in October of 1971, when Duane Allman died from internal injuries sustained in a traffic accident while riding his motorcycle in Macon.

Shattered, the group vowed to carry on as a five-piece. Recording tracks with Dowd at Criteria resulted in healing and the eventual, triumphant 1972 studio-and-live double-album Eat a Peach. Live tracks with the late Allman included the blues standard “One Way Out,” and his previously recorded studio contributions aided the Betts-penned “Blue Sky,” with the composer’s lead vocal — his first ever with the band — aiding the Southern rock classic. A Betts instrumental was also a highlight. “Les Brers In A Minor” mixed his jazz leanings with classical elements befitting of its title.

Yet Oakley never fully recovered psychologically from the loss of his friend Allman, the band’s ingenious slide guitarist. In November of 1972, Oakley crashed his own motorcycle into the side of a bus only three blocks away from Allman’s accident the year before, and eventually succumbed to cerebral swelling from a fractured skull. The remaining members, now down one-third of their original lineup, nonetheless vowed to carry on, adding bassist Lamar Williams (1949-1983) to replace Oakley and keyboardist Chuck Leavell instead of a second guitarist.

The resulting 1973 comeback Brothers and Sisters found Betts guiding the band; contributing the album classic “Southbound,” singing his country-influenced hit “Ramblin’ Man,” and adding another instrumental highlight in “Jessica” (a live version of which would win him a “Best Rock Performance” Grammy Award in 1996). The album climbed the charts, helping to make the Allman Brothers Band one of the top concert draws in the world, even as the remaining Allman brother was branching out by starting a solo recording career with his album Laid Back. By 1974, Betts released his own solo debut, Highway Call. And the Allmans were renting the customized Boeing “Starship” aircraft to tour Europe that had previously been used by Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones.

“When we got that goddamn plane,” Allman would later say, “it was the beginning of the end.”

Having relocated to Los Angeles, the band’s remaining namesake member would soon date, marry, record with, and divorce celebrity singer and actress Cher. Between 1975 and 1981, a series of sub-par albums with revamped lineups threatened the Allmans’ legacy. As did a hiatus that lasted through 1989.

But that’s the year Epic Records released the group’s retrospective boxed set Dreams, helping to lure Johanson back into a lineup fortified by the additions of Haynes and bassist Allen Woody (1955-2000) for revitalized live shows and recordings. Subsequent albums Seven Turns (1990), Shades of Two Worlds (1991) and Where It All Begins (1994), along with an annual residency at the Beacon Theatre in New York City, culminated in the Allman Brothers Band’s long-overdue induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995 by Willie Nelson.

The Beacon Theatre residency would last through 2014. Betts, however, would not. Growing tensions between he and Allman during the guitarist’s ascendancy boiled over by 2000, when Betts was served walking papers. Despite the sterling contributions of additions like guitarists Haynes and Derek Trucks (drummer Trucks’ nephew), bassists Woody and Oteil Burbridge, and percussionist Marc Quinones, the Allmans would release only one more studio album, Hittin’ the Note, in 2003. It would prove to be the only one ever without Betts. The group retired in 2014 rather than continue without the departing Haynes and Derek Trucks.

Butch Trucks would commit suicide in early 2017, and Allman would die months later from complications with liver cancer, leaving behind only original band members Johanson and a nostalgic Betts.

“I wasn’t able to talk to Butch because his death was so sudden,” he said. “But I’d been in touch with Gregg after I found out he was sick. We had some healing conversations, and even some laughs, talking about old times together. And I’m so glad we were able to.”

Often erroneously labeled Southern rock, the Allman Brothers Band also blended blues, jazz, country, soul, R&B, gospel and jam band influences over 45 years. It’s a mix that valiant successors from Lynyrd Skynyrd to ZZ Top could only aspire to. The Allmans teamed with the Grateful Dead and The Band in 1973 to play to 600,000 people in Watkins Glen, N.Y. — an audience larger than Woodstock’s. And in that era especially, the Allmans were the ultimate example of the sum being greater than its parts. All of its members were expert listeners, an undervalued musical quality, who knew the restrained benefits of using spaces between notes and beats in their musical conversation, not waiting for their chances to stand out through overplaying.

Inadvertently, Betts even went Hollywood in 2000 in the hit movie Almost Famous. The film depicts director Cameron Crowe’s days as a youthful Rolling Stone reporter on the road with multiple mid-1970s touring acts, including the Allmans. Crowe fashioned the lead guitarist in the movie’s fictitious band, Stillwater, to look like Betts. And actor Billy Crudup, portraying the character Russell Hammond, had the hairstyle, moustache and every mannerism down cold.

With 45 years of unparalleled versatility, dexterity, and influence, one could do worse than claiming the Allman Brothers Band was the greatest American group in the history of popular music. Duane Allman was its fiery impetus; Gregg Allman its prime voice, but its ultimate composer — the one who gave the lineup its jazz, country, and instrumental jam band elements — was the brother from Westgate.

Suggested listening

The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East (Capricorn, live 1971)

Eat a Peach (Polydor, studio-and-live 1972)

Brothers and Sisters (Polydor, studio 1973)

Shades of Two Worlds (Sony, studio 1991)

An Evening With the Allman Brothers Band: 2nd Set (Sony, live 1995)