By Tara Mitton Catao

With a weighty theme and a cumbersome title, Ballet Austin’s Saturday night performance of Light/The Holocaust and Humanity Project at the Kravis Center for the Performing Arts was anything but that. In short, it was arresting.

Artistic Director Stephen Mills’ evening-length work depicted a timeless universality molded by the purposeful choices Mills made while sculpting the personal story of Holocaust survivor Naomi Warren. The production had a pared-down look with a pure message that resonated with a rare clarity.

Devoid of any kind of violence, the viewer was presented with the human response to the horrors of the Holocaust. Clearly drawn from a deep study of the emotional memories of many survivors, Mills crafted a movement vocabulary that was fascinatingly different. His creative imagery was surprisingly concise and his choreography, with its endlessly original movement and partnering, was distinctive and powerful.

The sparse but very effective set design by Christopher McCollum was integrative to the production: imprinting strong images in our minds, helping move the events along and reminding us that whether it is the past, the present or the future, history has an unfortunate way of repeating itself. We humans keep finding awful ways to dehumanize each other: a universal message for today’s world.

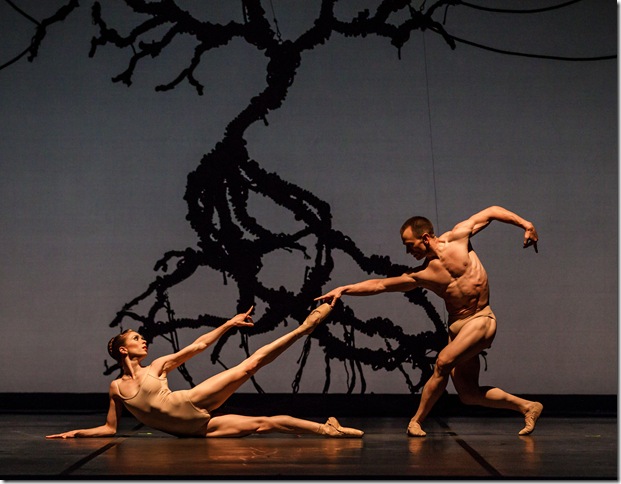

Mills used a sense of repetition throughout the work starting with the first couple, Adam and Eve, and the first circle of life. In silhouette, the lissome Ashley Lynn Sherman with her lovely line en pointe was seamlessly partnered in off-balance promenades by Frank Shott as they intertwined before a gnarled, leafless tree that had roots as long as its branches.

As light entered, the couple was joined by others, at first also silhouetted, who repeating the movement in a canon formation. More dancers entered, now dressed in everyday clothes, and danced together as a large ensemble to a lively folk music made of rhythms and voices. Repeating gestures, they began to form bonds as traditions became established.

A sense of close urban living was subtly established by the hanging of a multitude of white translucent rectangles low above the stage like bedsheets hanging to dry from tenement walls. As images of doors and windows were projected on the sheets, the mood changed. Couples, families and lone individuals, beginning to sense fear, raced through the transparent lanes trying to flee.

Rounded up and lined up in a harsh white strip of light under a low hanging black drape at the back of the stage, one by one, each had to suffer the humiliation of publicly disrobing. Here one could really see how every dancer was fully committed to his or her role as an actor.

Then came not the heart but the guts of the work: a section when relentless sirens blared for a disturbing amount of time as the clumps of people in their underwear were corralled and herded here and there into the smallest areas. The dancers were so credible, with their individual expressions of panic, as they were packed into the boxcar that transported them to the concentration camp or were piled one on top of the other into the gas chamber. These solid rectangles of agitated human limbs and faces were a potent image on the open stage.

Mills used the theme of the circle to illustrate that the same plight was shared by countless people. Eight dancers walked in a circle around a soloist, who first squatted before beginning to dance, as the group sporadically entered the circle to offer some support or empathy. The repetitive concept of eight solos starting exactly the same way — with the same squat — was saved by the endless invention of Mills’ movement and the power of the dancers’ performances.

All in all, the dancers of Ballet Austin are a special breed: focused, well-trained and artistic. Presented in the program as just a list of ensemble dancers (with the exception of the young and old Naomi Warren characters), these excellent performers melded into a collective at one moment and emerged as highly defined individuals at another. Every dancer was very versatile, possessing not only lovely ballet lines but also a firm command and deep understanding of contemporary movement.

The passing of time (or the loss of time in a void) was cleverly achieved with a projection of rapidly moving clouds on the scrim as the circle dance was repeated but this time, with more resignation, as the eight were confined behind the dark, high wall of a concentration camp.

Struggling to stay standing on their feet, they danced in the confinement of their small circle of those still alive. The excellent Aara Krumpe, who represented the memory of a young Naomi Warren, was the last to enter the circle and was joined by Paul Michael Bloodgood. Their resolve to keep moving on — to stay alive — was sealed with a determined kiss.

Naomi Warren, now 95, whose memories fueled Light/The Holocaust and Humanity Project, made one condition in order for Mills to use her story. She asked that there be a sense of hope in the work so that the audience wouldn’t feel that oppression can win in the end.

In addition to an ever-present light in a glass globe that was suspended high over the stage, Mills attempted to achieve this in the last section by revisiting the more balletic vocabulary with which he began the work.

Danced to the calming notes of Philip Glass’s Tirol Concerto, the women returned in flowing blue skirts and wearing their pointe shoes again. The five couples, continually making exits and entrances, seemed to serve the purpose of reassuring us that though humanity does some awful things to each other, the circle of life does continue.

However, after the strength of the raw exposure choreography in the center of the work, this last section (which seemed to go on too long) felt somewhat weightless. Perhaps that was the intention: to show that the good life is a bit thin — just a veneer — covering what really lies underneath.