By Katie Deits

WEST PALM BEACH — Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams were friends who shared a passion for the natural beauty of the American West.

On Saturday, an exhibit chronicling that passion — Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities — opened at the Norton Museum of Art. The show runs through May 3, and is worth repeated viewings.

If it hadn’t been for Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), the world might have not seen the work of painter O’Keeffe and photographer Adams. Stieglitz, a photographer and gallery director who brought avant-garde American and European art onto the New York art scene, gave both O’Keeffe and Adams the entrée into the exclusive world of fine-art collectors.

Stieglitz, who also was married to O’Keeffe and a tireless promoter of her work, would probably be pleased to see the staging of the exhibition, the venue, as well as the quantity of quality work displayed.

The exhibition includes 40 of O’Keeffe’s paintings and 54 black-and-white photographs by Adams. Seldom does one have the opportunity to see so many of these works displayed at one time. Visitors have the chance to peer into their worlds, share their vision of their environment and take home a widened frame of reference of how to look at the natural world.

Both artists loved the wilderness and were advocates for it. Perhaps they were some of the first environmentalists; Adams petitioned government officials to preserve America’s natural treasures. As a young man, Adams spent time in Yosemite, where his passion for photography developed.

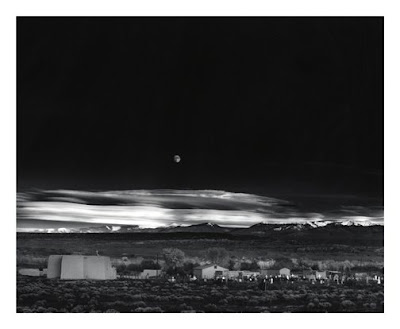

Ansel Adams, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941)

Ansel Adams, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941)The Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

It was by chance that the two met in 1929, when Adams was photographing a pueblo in Taos, N.M., and O’Keeffe was visiting the town with Paul Strand’s wife, Rebecca. O’Keeffe, at 42, was already an established Modernist painter, while Adams, at 27, was just embarking on his career. He must have impressed the painter, as she introduced his work to Stieglitz, who hosted an exhibition for Adams in 1936.

Thus began a long friendship, kept alive by their shared enthusiasm for the unspoiled natural beauty of the West and art. O’Keeffe moved to Taos in 1949 and lived to be 99, outlasting the younger Adams by two years; he spent most of his life in the Northwest and died in 1984.

The exhibit is divided into five themes: Nature Up Close, Architecture, Waterfalls and Mountains, Nature Abstracted, and Flowers and Trees. “It is not a one-to-one match-up of the artists’ work; they did not work that way,” said Marisa Pascucci, the Norton’s curator of American Art. In the Architecture-themed room, however, are images of a church that both artists captured from almost the same angle.

In the first exhibition room, Nature Up Close, is a 9-inch-by-7-inch O’Keeffe canvas, The Black Iris. “It’s small, yet exquisite,” Pascucci said. O’Keeffe’s masterful use of color and gradation call attention to the patterns and shapes of natural forms.

For his part, Adams often worked in sequences, Pascucci said, in works such as Snow Sequence I, II and III, showing snow melting away from rocks. These detailed photographs of abstracted shapes is further evidence of Stieglitz’s influence on Adams and a shared vision with O’Keeffe, yet she was always looking for ways to simplify the form and minimize detail, while Adams tried to show texture and detail in the surfaces of his subjects.

Labels in the exhibition are peppered with the artists’ quotations, such as these:

“Nothing is less real than realism…Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.” — Georgia O’Keeffe, 1922

“There is no human element in the High Sierra…But there is an extraordinary and sculptural beauty that is unexcelled anywhere in the world.” —Ansel Adams, 1938

Humans and animals are absent in the paintings and photographs, aside from Adams’ photos Woman Winnowing Grain, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico and a small silhouette of a horse in Winter Sunrise, the Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine, California.

From left: Barbara Buhler Lynes, curator, and George G. King,

From left: Barbara Buhler Lynes, curator, and George G. King,director, of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M.;

and Marisa Pascucci, curator of American art at the Norton.

To the left of Lynes is O’Keeffe’s Pelvis With the Moon – New Mexico. To Pascucci’s right is Ansel Adams’

Lake Near Muir Pass, Kings Canyon National Park.

(Photo by Katie Deits)

The book that accompanies the exhibition features an essay by Barbara Buhler Lynes, a curator at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. Lynes, who attended the Norton opening, explained how the artists’ approaches differed.

“Adams was interested in the transitory — the sunrise, rainstorm, a geyser. O’Keeffe felt nature was an ongoing phenomenon — with a sense of permanence,” Lynes said. “Adams also did commercial photography…he was a teacher and developed the zone system for exposure.”

Adams was a master printer, “but as he aged,” she said, “he printed more dramatically. He was a huge influence on photography.”

On Sunday, there was standing room only at a lecture by Adams’ former photographic assistant, Alan Ross, who shed more light on Adams’ life, gregarious personality and philosophy. Adams, a very active child, dropped out of school in the third grade and self-educated himself in art, science and music.

Ross said Adams photographed with a large-format view camera and, when he started out, used glass negatives. “With a big camera, you have to want the image; it’s not a casual enterprise…Adams would pre-visualize a photograph and then manipulate it in the darkroom. He would say, ‘I envision the sky much darker,’ so he would print it to his vision. It was a matter of tonal balance. He just felt that was part of the art.”

Adams’ famous Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico is an example of Adams’ mastery of photographic printing. “Adams liked black-and-white photography. It is automatically an abstraction of reality — very freeing,” Ross said.

The Norton exhibit marks the first time that a major show has paired the two artists in such a way. It was organized by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and was made possible in part by MetLife Foundation, The Burnett Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum National Council. The Norton’s Web site also has a video about the exhibition.

While you’re visiting the Norton, take a few minutes to see the contemporary portrait exhibition at the museum titled Striking Resemblance: The Portrait as Muse, which will be on view until Feb. 15.

Part of the exhibition is a series called German Indians, by Andrea Robbins and Max Becher. Robbins and Becher, who met in fine-arts college, collaborate on photography, video and other projects, and are married to each other. They photograph projects worldwide, exhibit in major museums and, since the tragedy of Sept. 11, commute between their apartment in lower Manhattan and their geodesic-dome home in Gainesville.

Becher is the son of famed photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, who spent more than half a century documenting the beauty of industry buildings throughout the world and influenced artists such as Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth.

“We take pictures of places that look like other places, but don’t belong where they are,” Becher said.

German Indians is a series of portraits taken at a festival in the hometown of German 19th- century Wild West novelist Karl May, who portrayed Native Americans as “the Noble Savage,” Becher said. “Historically, the ‘picturing’ of Native Americans has always been through an Anglican eye. These Germans are preserving costumes and customs that may no longer exist anywhere else.”

These photographs convey the feeling of displacement as viewers do a double-take at the strange, pale, blonde “Indians.”

Robbins said photographer Walker Evans had been a strong influence on their work, “with a sense of a constructed reality. We have very strong opinions, but meaning and artwork changes over time.”