(artist: Art Stenholm; designer: Ed Krinsky)

By Jan Engoren

As video killed the radio star, so did it kill the pinball machine.

And as a new exhibit of nostalgic Americana at the Cornell Museum of Art and American Culture in Delray Beach makes clear, the rise of computer technology and video have sent pinball machines down the road of forgotten Americana: the automat, the Victrola, the jukebox, the 1959 Chevy.

Pinball machines were in their heyday from the 1930s to the 1970s, found everywhere from beachside arcades to bars, pool halls and candy stores. The Cornell now has 28 of them on display from the collection of Florida resident R. Steve Alberts in an exhibit that runs through the end of March.

Today, collectors prize the machines not only for the game but for the original artwork on the side panels, gameboard and backglass. It’s worth spending some time at this exhibit if for nothing more than to be reminded of a simpler time and a pastime that has gone the way of the transistor radio.

This exhibit, with a good sampling of some of the best-known games, fills two large rooms and a part of a third. It is evident that the curators attempted not to recreate an arcade but to display the machines in a manner befitting a museum, and also to showcase them as a way to introduce the machines to a younger generation.

“The museum has recently refocused itself to reach a younger demographic and has renamed itself the Museum of Art and American Culture,” said Joe Gillie, Cornell’s executive director. “We believe this will help us come into our own as a museum and showcase exhibits that are relevant to our younger visitors.”

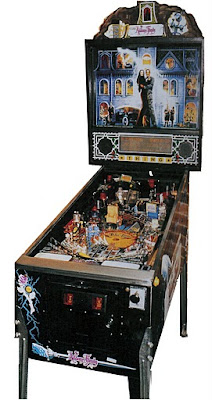

Bally’s Addams Family game, made in 1991,

Bally’s Addams Family game, made in 1991,and the best-selling pinball machine of all time.

(artist: John Youssi; designer: Pat Lawler)

Of particular note are many of the most popular games of recent eras, such as the Williams Company’s Black Night, circa 1980, which has the first multi-level gameboard; the Haunted House with three levels, by Gottlieb; and the best-selling pinball machine of all time, The Addams Family, created in honor of the camp 1960s TV series after Williams and Bally merged in the late 1980s.

The primary audience for many of these games was adolescent males, and you can see why when you look at the artwork, much of which features buxom, curvaceous women, comic-book heroes such as Spider-Man and the Incredible Hulk, TV shows such as Star Trek and Bonanza, sports heroes such as the Harlem Globetrotters and Muhammad Ali and even a patriotic red, white and blue Evel Knievel with a blonde woman in hotpants and tight T-shirt.

The golden age of pinball is considered to be the decade from 1948-58, due in part to the Gottlieb Co. adding “flippers” to a game called Humpty Dumpty. Flippers gave the player some control over what had been purely a game of luck and transformed it into a game of luck and skill.

Before that, pinball had been considered something of a dodgy pastime. During Prohibition, pinball machines were blamed for helping lead young men into lives of gambling and crime. One picture in the exhibit makes that point: It’s New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia smashing a pinball machine with a sledgehammer.

Despite their checkered past, pinball machines rebounded in popularity and secured their place in popular culture. The 1970s saw the second biggest advance in the industry since flippers. Solid state technology, computerization and electronic displays came into existence, making the older mechanical games obsolete.

English rockers The Who immortalized the Pinball Wizard in their 1969 rock opera, Tommy. An early 1970s machine named after it is here in the exhibit; actress Ann-Margaret, who starred in the film version, modeled for the backglass artwork.

Adding to the ambience of the exhibit is a collection of neon pinball and arcade signs on loan from the Puppetry Arts Center in Palm Beach as well as assorted pinball ephemera, such as pinball ornaments, arcade tokens and collector books and posters. A real treasure is the Coke machine piggy bank designed to replicate a miniature pinball machine, complete with moving parts.

The neon pinball and arcade signs could have been used to better effect by mounting them in a concentrated display, creating more of a tone and feel of an actual arcade and better evoking the feel of a lost era.

The backglass art for Darts, made by Williams in 1960.

The backglass art for Darts, made by Williams in 1960.(artist: George Molentin; designer: Steve Kordek)

In the main exhibit hall, I recommend viewing the short mini-documentary, Tilt: The Battle to Save Pinball: Year 2000. It is fascinating to watch as the Williams Co. designers and developers, as well-known in their industry as Bill Gates or Steve Jobs are in theirs, discuss their last-ditch attempts to save the endangered game and their efforts to compete in the new video marketplace.

Their vision resulted in the first combined video pinball machine called Revenge From Mars. The film runs about one hour, and if you can’t spend the whole time, at least try to listen and get a sense of an era of American inventiveness.

Just to the right of this film, sits the actual game that is the subject of the documentary, Revenge From Mars, developed by Williams before it closed down the pinball division of its company and concentrated on the business of making slot machines.

Unfortunately, viewing this machine in its static state is like watching a 3-D movie without the glasses. To see Revenge From Mars in all its glory and to understand the full impact of its innovation would require you to play the game, which isn’t possible.

For me, the exhibit could reach another level by recreating more of the actual ambience (without the smoke, of course) of a traditional arcade and by having more than two machines available to play.

In its upstairs display, the museum does have two working machines that the public can play – the Williams F-14 Tomcat on loan from the personal collection of Christopher Lemon, and The Games, by Gottlieb, on loan from Joey Restivo and Metropolis Entertainment. The original cost? 1 play (five balls) for 25 cents.

Try it, and do more than test your skill. Reclaim a piece of Americana.

Jan Engoren is a freelance writer based in South Florida.

Pinball Palooza: The Art, The History, The Game runs through March 28 at the Cornell Museum of Art and American Culture at Old School Square in Delray Beach. Hours are 10:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, 1 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $6 general; $4 seniors and students 13-21, $2 for ages 5-12 and free for children under 5 years old. Delray Beach residents receive free admission the first Sunday of each month through April.