By Sandra Schulman

Hand-poured glass spells poetic words, while embroidered photos tell stories.

In a genre he has created and perfected, Rob Wynne is having a survey exhibit at Gavlak Palm Beach, The Underside of a Leaf, of new and historical works. A selection of Wynne’s iconic poured glass pieces is shown alongside his archival “photograms,” and text-based works from the 1970s and 1980s. This presentation coincides with the release of Obstacle Illusion, Wynne’s monograph, published by Gregory R. Miller & Co. and named after a phrase a cab driver said to him.

Though he uses a range of techniques and mediums, poured glass has become central to his work, a process that came about by accident, and has now been featured in sprawling multi-story works at the Norton Museum and high-end designer stores.

In his “Embroidered Paintings,” he embroiders words and phrases like “come back” over found images he sends-up and complicates, where the serious and playful reflect each other.

The commonality is that Wynne has always used text and continues that with the glass.

“When I got out of art school, I became friends with Ray Johnson,” Wynne says. “A post-Fluxus artist, very active on the downtown New York scene in those years of the late ’60s or early ’70s. He had something called the New York Correspondent School, where we sent art postcards. I went to Western Union where they sent telegraphs and I sent myself a telegraph which said, “I am still alive, (signed) Rob. That was the first time that I realized the kind of elegiac power of language and text. And it stuck in my brain.”

From there he used Xerox and went to print shops to make copies of things.

“A lot of my friends were doing experiments with video and performance art, poetry, except I used to go all the time to St. Mark’s to the poetry project there. In those years, it would be Allen Ginsberg and Anne Wallman, really interesting people. I was was invited by The Kitchen to do an installation and I weirdly chose a glass marble. It was my first thought of the material of glass, but I wasn’t even using it as a material. I just spun a glass marble perpetually in a video monitor. And then I blew up an image of it and plastered the wall with blueprints of it.”

“Putting the book together was fascinating because I had never really thought of the trajectory of my work. I was just in the moment of making art all the time, but I realized that I experimented with so many different things. I started making paintings, collages, but there’s a direct line with text and glass.”

Wynne did a show of thread drawings where he sewed text onto transparent bellum, where one could see the threads that made the text and the back of the language.

says that “Having suffered from dyslexia, which is not uncommon, I was always curious about how does the word get formed, how does language begin? And the thread drawings illustrated that conundrum of seeing abstraction in the back of the language, which is my language.”

“The name of the book, ‘Obstacle Illusion,’ was overheard. I was taking a taxi ride somewhere back in the day and the cab driver turned to me. ‘Hey did you see that?’ And I said, ‘See what?’ He said, “It was an obstacle illusion.” And I thought, oh my God, that makes sense.”

His glass work started when he tried to make a cast at a studio.

“I didn’t know anything about glass. I made a plaster cast of my feet, took it to the glass studio. And while the technicians did it, I saw people bustling about with these big ladles full of molten glass, taking a hot liquid that then becomes solid. And I thought, I would like to draw with this. I could make letters and put together phrases or single words.”

“The technicians said, ‘Well, you really need to have a font and make a cast and you pour it into the mold.’ And I said, ‘Why? It’s liquid. I’ll just pour it onto the metal table and make a word.’”

They suited me up, gave me a very heavy, hot ladle of 1,900 degree-Fahrenheit glass and a 50-pound ladle. On my way to the table to pour the first letter, it fell out of my hand. I just couldn’t hold it. It was too much, it was too chaotic. They said, ‘Don’t worry about it. We’ll clean it up.’ I said, ‘No, save it, save it. Eureka!’”

From there he figured out the process of controlling the ladle to spell letters, putting silver nitrate on the back to make the mirror, then drilling a small hole for a screw to affix to the wall. Paper templates for literally thousands of pieces of the glass would come later as the work became more and more elaborate.

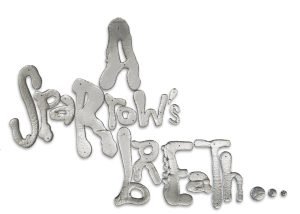

Over the years he collected words and phrases to inspire the mirror art.

“I had a little notebook, I wrote things down. Now I put it on my iPhone. I would either think of parts of things that I was reading, like Japanese haiku because I love the kind of minimal, very tender way that they underline certain things. The title of my show, ‘The Underside of a Leaf,’ comes from a haiku poem.”

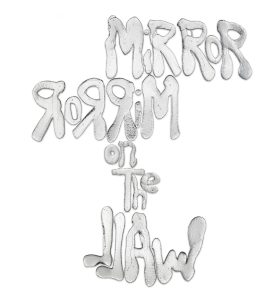

In the work Mirror Mirror on the Wall (2023), Wynne borrows the line from Snow White’s fairy tale, playing with the word “mirror” by flipping it horizontally, the way an image would be reflected in the material itself.

How does Wynne feel looking back on these earlier works?

“In revisiting them and seeing them, honestly, some of them really resonate with me. Some of them I have very different memories of even having done though so long ago. It’s a survey to mirror the work that we chose for the publication.”

The Underside of a Leaf runs through March 24 at Gavlak Palm Beach, 340 Royal Poinciana Way, Palm Beach. Visit www.gavlakgallery.com or call 561-833-0583.