Canadian journalist Meg Federico woke up one day to find herself a member of the sandwich generation, torn between caring for her own young children in Nova Scotia and her elderly mother, who was descending into dementia in New Jersey.

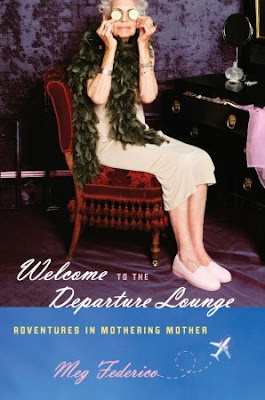

In her memoir, Welcome to the Departure Lounge: Adventures in Mothering Mother, Federico writes compellingly of the tug-of-war between the two, always thinking of the place she isn’t as she ping-pongs back and forth between Canada and the United States.

The book opens with Federico’s 81-year-old mother in crisis after a drunken fall during a vacation trip to West Palm Beach. Federico flies down, telling her family she’ll be back in a week. But the days drag on as she tries to make arrangements to get her mother back to New Jersey, upsetting her children, her husband and her newspaper boss:

“ ‘Mommy, come home!’ my daughter sobbed on the phone. She hated the babysitter, whose enthusiasm for my family had waned with each extra day of duty. …

If I packed up and left, I was a bad daughter; if I stayed, I was a bad mother. But, for me, bad-daughter guilt trumped bad-mom-spouse guilt. Practically speaking, I had plenty of time to make up for being a bad mom, but with the sand running out of the hourglass, hardly any time left to be a good daughter. I told myself the kids would survive. I told [husband] Rob I had no choice, and neither did he.”

Federico initially thinks that once she gets her mother, Addie, home to New Jersey, everything will be fine and she can go back to her life. But rather than an ending, it’s just the first step as her mother regresses and becomes more ill.

In many ways, it’s perplexing that Federico feels such loyalty and a need to care for her mother, when Addie apparently didn’t do much caring for her during her childhood. Federico describes how her mother, irritated that she got out of bed sometimes to play instead of sleeping for the 12 hours required by Addie, tied her wrists and feet to the bedposts and left her there. When a servant questioned the harshness of the “lesson,” Addie snapped, “When I need advice, I’ll ask for it.”

The family’s children under the age of 6 ate in the kitchen with the servants. But Federico says that when she was finally old enough to eat with the rest of the family, she missed being in the kitchen. In the dining room, the meal was not pleasant.

“Mother played a little power game I call ‘Interrogation.’ This is a tried and true method of social intercourse that replaces conversation. The interrogator (a.k.a. Mother) almost never ventures an opinion of her own. Between bites of food, she questions the interrogatee, who struggles to manipulate the heavy silverware correctly while coming up with a satisfactory answer. As you floundered, Mother critiqued your table manners, pointing out your mistakes by flicking her middle finger sharply against the back of your hand, if you were in range.”

Not exactly nurturing, but then it’s not unusual for children of passive-aggressive, manipulative mothers to grow into adults who still seek approval they will never receive.

Things had been going downhill for Addie long before her collapse in West Palm Beach, but Federico and her siblings had been in denial, blaming Addie’s new husband, Walter, for limiting their time with their mother:

“Addie and Walter did a great job of acting almost normal for the span of an afternoon or an evening. If the odd situation or non sequitur popped up, it didn’t raise the alarm. After all, there they were, just like always, if a bit older. Addie in her familiar skirt-and-sweater set, Walter in his suit and tie, drinks before the meal and goodbyes after the dessert and coffee. We had no way of knowing that Mom’s sweaters were often stained, and the Band-Aids on her arms and legs were always there. We just didn’t know.”

But while there are many heart-tugging moments in Federico’s memoir, there also is plenty of humor. She and her brother, William, call Addie’s house “the Departure Lounge” because being around Addie and Walter, who eventually is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, is like leaving for another dimension.

“How’s life at the Departure Lounge?” William asks during a phone call. “Let’s just say the drinks are outrageous, and they never run out of nuts,” she replies.

And Federico has a way with words that can make even the most cringe-worthy details seem funny:

“There are some things a child shouldn’t have to deal with, even as a grown-up. One of those things is your parents’ sex life. When I was a child, I shuddered upon learning the facts of life. I’d vaguely imagined I was conceived through a telepathic mental process, not this implausible physical bumping and grinding that my respectable father and mother allegedly performed – for pleasure!

There was nothing in their attitude, nothing in their opinions or comportment, to support the veracity of this claim. How freaky could it get? The answer is, a lot freakier. As Walter’s mind deteriorated, his private parts perked up. Thanks to an abundance of geriatric health-aid catalogs, Walter could be considered armed and dangerous on that score.”

Unlike many of the sandwich generation, Federico is fortunate that money is never an issue. Her parents were clearly quite wealthy, and Addie’s funds are sufficient to pay for whatever she needs or wants. Since she does not want to live in a nursing home, Federico hires as many people as necessary to keep Addie in her own home. At one point, Federico says, the payroll grew to 15 people caring for Addie and Walter at a cost of $400,000 a year.

And there’s still enough money that, when Addie feels the urge, she and her entourage head into New York City and drop $100,000 at an art gallery. That’s not the kind of situation that most people faced with caring for elderly parents will be in.

Welcome to the Departure Lounge is both entertaining and immensely sad. Federico, a longtime newspaper columnist who also has created documentaries for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, has a flair for vivid descriptions and a witty turn of phrase, which helps lighten what is otherwise a quite depressing subject.

She does not stint in describing the details that many facing an elderly loved one’s end of life will experience, although the timeline is sometimes hard to follow as she jumps from present to past and back to present repeatedly through the book. But that’s also natural when looking at an elderly family member such as Addie, contrasting her present with memories of her earlier days.

WELCOME TO THE DEPARTURE LOUNGE: Adventures in Mothering Mother, by Meg Federico, Random House, 191 pages, $25.

Aviva L. Brandt, a freelance writer based in Portland, Ore., previously worked for 15 years as a writer and editor for The Associated Press.