By Jan Engoren

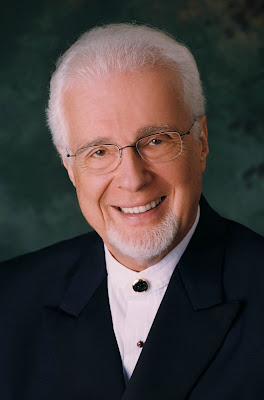

Born in Brooklyn in 1934, pops pianist Peter Nero (né Bernard Nierow) began his formal musical education at the age of 7. At 14, he was accepted to New York City’s prestigious High School of Music and Art and won a scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music.

A two-time Grammy award winner and 10-time nominee, Nero has released 68 albums over a career of 50 years. His early affiliation with RCA Records produced 23 albums in eight years, and his ensuing move to Columbia Records earned him a gold album for The Summer of ’42.

Since 1979, Nero has been the music director of the Philly Pops, which he founded, and does double duty as both conductor and performer. He did the same thing for the Florida Philharmonic throughout the 1990s and into 2003, the year the orchestra failed.

This Friday and Saturday, Nero returns to South Florida to perform with his trio at the Eissey Campus Theatre in North Palm Beach, and at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

Jan Engoren spoke to Nero from his home in Philadelphia, where after a busy day of phone calls to the West Coast and taking care of the business side of music, he finally sat down to a very late breakfast and a bowl of high-fiber cereal.

They talked about his Brooklyn boyhood, his nostalgia for 5-cent fountain Cokes, his admiration of, and friendship with, pianist Vladimir Horowitz, his love of crossword puzzles, technology, and women.

Engoren: Congratulations on your long career. How have you manged to survive all the changes in the music industry and changes in technology?

Nero: Well, it’s 50 years since I made my first recording. I made my first recording, Piano Forte, in 1960. It was released in 1961. In 1962, I was presented with a Grammy award for best new artist. So, you see, I can drag this 50-year anniversary out for the next three years.

If you go onto the Grammy Awards website you can see who won best new artist, starting in 1957 when the awards started, and you look and see how many people are still around. They may be still alive, but they’re not making music. I’m very thankful to still be making music and working in a field that I love.

Engoren: Since the music industry is now fairly segmented and each radio station plays a particular type of music, how do you get exposure these days?

Nero: Well, I think the internet has taken care of that. These days more people download your songs than buy your CDs. I Google my name to stay on top of the business. I can get a pretty good picture of downloads of my songs and I have a total of 68 albums that I worked on. Of course, they’re not all currently available, but they always show up on eBay in LP form.

Engoren: Who is your typical audience member?

Nero: My audience is getting younger. Either that, or I’m getting older. They used to be 55 to 75 years old, and now the average age is between 45 to 65 years old.

Engoren: I think it’s more difficult now for new people to break into the music industry unless you are Lady Gaga. What was your experience like?

Nero: Yes, if I was starting out now and trying to break into the music industry, I’d be selling pianos – not playing them!

There are many talented people out there who need some hope and encouragement for the future. I made it by pure luck and coincidence.

When I was in Juilliard, they had a joint program with the New York classical radio station, WQXR. Abram Chasins, the music director and protégé of [pianist] Josef Hofmann, created the classical music format and started a program called Music in the Schools. They held auditions for pianists with some very esteemed judges, including Arthur Rubinstein, Rudolf Serkin and Vladimir Horowitz.

I had the honor of closing the seventh week. It was a half-hour broadcast. I was so nervous, I hardly remember what I played. I was 17 years old. Sometimes I think the younger you are, the more nerve you have. My wrists would get tired when I played, so I asked Chasins for some tips to help with my playing.

At first, he was reticent to do that because he knew I had a teacher and he didn’t want to interfere. But, I convinced him. He had retired from being a concert pianist. He sat down at the piano and still had perfect execution and perfect musicality. The fluidity and the ease with which he played; the variety of tones he had. He taught me something.

I had been taught to keep high fingers and stiff wrists – you could balance a glass of water on my wrists; no movement allowed. That was the current school of thought but really, the complete antithesis of the way it should be.

At that time, they misanalyzed Vladimir Horowitz’s playing. It was thought that having stiff wrists was the proper technique. But in reality, nobody was more relaxed than Vladimir Horowitz, and he was in total control.

When I was a kid, I used to go to all his concerts. I would get up early to wait on line at 6 a.m. for tickets to go on sale at 10 a.m. I’d arrive at 6 a.m. and be first on line. I’d freeze to death for four hours, but I’d get two tickets for the last balcony for $1.20 each. Throughout the concert, I’d be sitting on the edge of my seat.

When I began recording, Chasins invited Horowitz to come to a benefit performance I was doing in 1963. I have a picture of us together at that party that I treasure and value with my life. I sent a duplicate to him to autograph. A month went by and I called his secretary, Bernice, and said, Is he going to sign that for me? And she said, yes, I was going to drop you a note saying he said he’d be very happy to do that for you, provided you do the same for him.

He was my idol and my favorite classical pianist. He was a pretty easygoing guy. Child-like; always smiling and always happy.

So, sure enough, he sent me a picture, after I sent one to him. It took me about a week before I could think of what to sign. I didn’t know what to say. I think I signed, “All the best… from Peter.” When I received his signed photo, I couldn’t read his handwriting.

I still have it. It was hanging on my wall until recently until I noticed the ink fading. I took it down and it’s packed away for safekeeping.

Engoren: How did you get your first break?

Nero: In 1960, RCA Victor records was looking for a male singer, a female singer and pianist. For the male singer they found John Gary, and the female singer was Ann-Margaret – that’s how she broke into show business. I became the pianist.

The music industry was a lot like the studio system in the Golden Age of Hollywood with movie studios like Paramount and MGM. The talent were nurtured and nursed and trained into the right roles. It really paid off, because they turned a lot of people into stars with long careers.

At that time, they looked for people to sign for three years. At the end of three years, if you got your foot in the door and had decent record sales, you had a guaranteed 20-year career.

The industry looked toward the future, which no one does anymore. Nowadays you have to sell a million tunes or you are off the label. I had the hottest manager: Stan Greeson. He had a lot of experience and we were together for 12 years, from 1960 to 1972, when he left the business. He was terrific. Everything came together at the right time.

I cut a demo record and he got so excited when it was finished. He came running out of the control booth and said, “I’m taking this demo over to RCA right now. And I can guarantee you, you will have a contract within three days. And if not, I will take it over to Columbia or Capitol.”

And sure enough, I had a contract the next day.

In my wildest dreams I did not think that my original technique of combining jazz and classical styles would become commercial. I wasn’t trying to create a new style, it was just me.

“Commercial” - that is the word they used. Traditionally, I was considered “artsy,” or for a “niche market.” The thought was: Who is going to buy this stuff?

The disc jokeys were the ones who made me. They played my records day and night. William B. Williams on WNEW in New York, in Make Believe BallRoom. Mel Baldwin in L.A., and Hugh Lampman in Dallas.

The industry was more optimistic in those days. They held a long-term view, whereas now, as Bette Midler once said on the Grammys, “Welcome to Hollywood, where you are as good as your last three minutes.”

Engoren: Besides Vladimir Horowitz, who are your other favorite musicians?

Nero: Art Tatum is my favorite jazz pianist. He was a very sophisticated player and a complete jazz pianist in every respect. He was very technical. Horowitz used to go to see him and was amazed.

Engoren: Do you listen to your own music? What type of music do you listen to relax?

Nero: I listen to most of my music on the computer, and mostly for work. I download everything. I put on a good set of headphones and earbuds. I download the material from iTunes and that’s how I get an idea of timing, making cuts and listening to the music before I buy a score. Currently, I’m busy preparing programs for the 2010-2011 season of the Philadelphia Pops.

But usually, I can’t relax and listen to music because I’m analyzing everything. Music doesn’t relax me. Crossword puzzles do. I’ve been doing the New York Times crossword since I was 15.

Engoren: Do you do it in pen?

Nero: Pen. It’s the only way.

Engoren: In addition to being a prolific musician and conductor, I see that you invented a software program.

Nero: Well, I’m kind of a techno freak. I was the spokesperson for the Consumer Electronics Show for 22 years and also for Tandy Corporation [RadioShack]. In the late 1970s, they came out with the first desktop micro home computer, the TRS-80. As a result, I got everything they produced. I have unit No. 26. No. 1 is in the Smithsonian.

I also wrote relational databases even though at the time, I didn’t know what they were called. I used them to check and see what music I played during my last performance at a particular venue. That way I could pick out material that I didn’t play previously.

We’re in our 31st year with the Philly Pops, and doing four to six programs a year and occasionally with run-outs, even more than that. So, it comes in very handy.

Engoren: Have you checked to see what you played at FAU 10 years ago?

Nero: I was about to do that, but this time I’m coming with my trio and not with a big orchestra, so the music selection will be different.

Engoren: I’d like to ask you: What’s on your iPod?

Nero: Actually, I have the Apple iTouch with 5,000 downloaded recordings. It’s a simple download process and plus you can access wi-fi on it. I use it when I don’t have my laptop with me. I also have three phones, each for a different purpose. I guess you could say I’m a technocrat.

Engoren: If you hadn’t become a musician, what would you have liked as a profession?

Nero: I would have become an architect. It’s very mathematical and structural, similar to music. A friend once said to me: “You’re lucky because you know what you want to do.” And I said to him, “You’re lucky, because you can decide what to do. I didn’t have much of a choice, because I’m riding a crest that’s pushing me in a particular direction.”

Engoren: What advice would you give to aspiring musicians in this day and age?

Nero: It is a very difficult and competitive business, so it all depends on how much you love what you’re doing. If you love what you’re doing, it helps to make it pay off. The odds are better. If you want to get a record made now, you have to really make it yourself.

Engoren: What else would you like to accomplish that you haven’t yet accomplished?

Nero: I’d like to do more piano playing and more writing. Coming to Florida will give me a good chance to go back to playing piano again. I’ve been doing so much conducting and learning music for these programs, I haven’t had time to devote to my playing.

I enjoy it. When I play for a [Philly Pops] concert, I have other things I have to think about: i.e., conducting the singers. Sometimes we have 300 people on stage. We have a chorus, a gospel choir, soloists, the orchestra, etc., so I am looking forward to simply playing the piano.

Engoren: Looking back over your long and varied career, are there particular highlights that emerge?

Nero: I’m very passionate about music and women. Unfortunately, sometimes I hold people to a high standard of excellence, as I do with music. This is an artistic syndrome where I can fall madly in love and everything is great until it’s not. This has been my downfall. That’s why I’m still working. There’s always a price to pay.

But, I don’t look back. I’m always looking ahead to the next concert. If I look back I see something I didn’t like. I don’t believe in resting on my laurels. I always strive for excellence. That’s what they taught us at Julliard.

I always try to make it better each time. It’s a disease. I’m never happy with what I’ve done. I’m always thinking, I’ll be better tomorrow.

Peter Nero will appear with his trio Friday at the Eissey Campus Theatre in Palm Beach Gardens, and on Saturday at the Carole and Barry Kaye Performing Arts Auditorium at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. Tickets: $50-$55. Call 561-278-7677 for the Eissey Theatre show, and 1-800-564-9539 for the FAU show.