When a time is no longer being captured, but simply being copied, that is the signal for someone to grab it and portray it like nobody else.

A group of rebel artists living in Paris heard that call in 1880. A new wind of creativity stormed the bohemian city for the next 30 years, stripping its walls of anything resembling old academic practices in order to hang fresh artistic tendencies. The new generation fighting for artistic liberation carried distinctive styles within it.

Its modern artists came to be known as Naturalists, Symbolists, the Incohérents and the Nabis. They gave Paris an art transfusion and in turn, Paris fed them inspiration through its theatres, cafés, cabarets, and circuses. One artist among them remains a symbol of that modern Parisianism: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who would have turned 151 this year.

His art is supposed to be the main focus of an ongoing exhibition at the Society of the Four Arts, but drowns in a sea of more intriguing works to the point that the show’s title should be reversed.

Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880-1910 celebrates oil paintings, watercolors and drawings by this group of rebels. Mary Cassatt, Emile Schuffenecker, Edmond Gros, Charles Lacoste and Jacques Villon are represented through landscapes, domestic views, circus scenes and cafè scenes. Also featured are rare zinc shadow puppet silhouettes that, most likely, never have been shown in the United States.

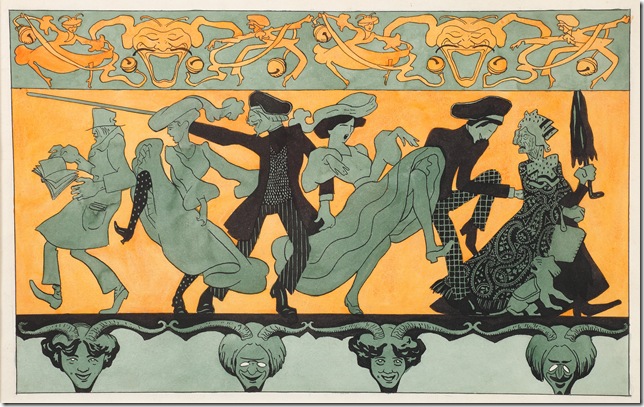

The zinc cut-outs were created by Henri Rivière and his colleagues as part of the 40 shadow productions for the famous Chat Noir cabaret shadow theater. The silhouette designs were originally made of cardboard before zinc’s durability made it the preferred material. They are fun to look at as they stand still, but to imagine them performing is even better.

It is not that Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters are not great and bold. The extravagance in his 1895 Marcelle Lender lithograph, with the actress’s double chin and nostrils emphasized, is quite a sight. So is his poster for the La Revue Blanche journal, which has a certain Japanese quality.

The story has it that the female model depicted here in a polka dots dress was not pleased to be working on the poster despite being friends with the artist. She is the picture of sophistication as she leans to the right and glides over the ice. Her skates are not visible.

As amusing as they are, these images are too familiar and lack the element of surprise. If there are indeed two Toulouse-Lautrecs (the glamorized works and the more intimate ones), as a recent story in The Guardian suggested, then this exhibition is not aware of the less-popular one.

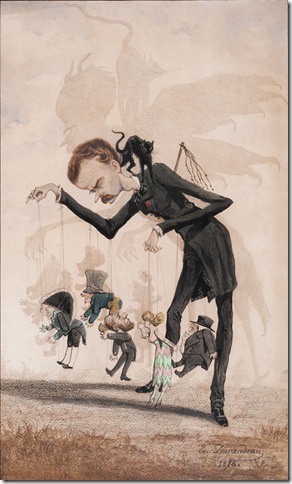

Visitors should not feel indebted to a name just because it is overly promoted. Instead, they should spend time exploring and discovering pieces like Ferdinand Lunel’s Illusion of the Evening (1900). Meant as a preliminary study for an illustration, the creepy image features a woman heading straight toward the viewer and being followed by a remarkably erect man. At first, it looks as if the ink has distorted her features, but she actually could be wearing a carnival mask. It is not clear whether the elegantly dressed man is her companion or a stranger. Either way, she is in a rush. An approaching horse carriage adds to that sense of urgency.

For a touch of comedy, visitors should head toward Jean Veber’s La Cariatide, where a rainbow of expressions is put on display. Initially, it looks like a typical gala night with the ladies and the gents dressed to impress. They have shown up to the show armed with binoculars and jewels. But a closer look reveals something hysterical: the real show is them. Some look pleased while others look absolutely bored, distracted and mortified.

When the circus emerged as an important venue of entertainment in Paris during the late 19th century, Henri-Gabriel Ibels was one of many artists to become interested. Acrobats, clowns and acts involving animals became the artist’s subject matter. His 1895 pastel piece The Clown places the performer halfway down the steps and in such a way that it is hard to resist his inviting gesture to get closer. He sports a yellow outfit with red dots that match his red nose, but despite the colorful garment and painted smile, there is something sinister about him.

Behind him, a ballerina appears to be warming up. Ibels has given her a softer pose and colored her attire in lavender. Later in the show is a series of works by a group of avant-garde artists Ibels actually helped establish. The Nabis, which means prophets in Hebrew, promoted flatness and simplified abstract form. They were also fond of Japanese prints, which explains the thick outlines.

One of the few women represented here is Elisabeth Sonrel, whose October watercolor combines naturalism with symbolism. Her admiration for the Renaissance painters, particularly Boticelli and Raphael, comes across here through the female romantically portrayed in soft, pale tones. She personifies the month of October while the landscape seems to have been inspired by Brittany, a region the artist regularly visited and portrayed.

Housed in the Esther B. O’Keeffe Gallery, La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880-1910 runs through Jan. 11 and will head to Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum next.

Seeing the artworks displayed reminded me that the desire to break free from the norm cannot be helped by an artist. Inevitable too, is that the works produced while and after that freedom is obtained make history in ways magnificent artworks don’t.

Even if visitors show up for the Toulouse-Lautrec represented here, they should plan to see a lot more. A good hour should be sufficient to walk all the rooms.

Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne runs through Jan. 11 at the Society of the Four Arts. Hours at the Esther O’Keeffe Gallery are from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays. Admission is $5. Call 561-655-7226 or www.fourarts.org.