Imagine you are a daunting century-old sepia image holding the secrets of a lost civilization. What more could you possibly want? A little credit for your creator, perhaps.

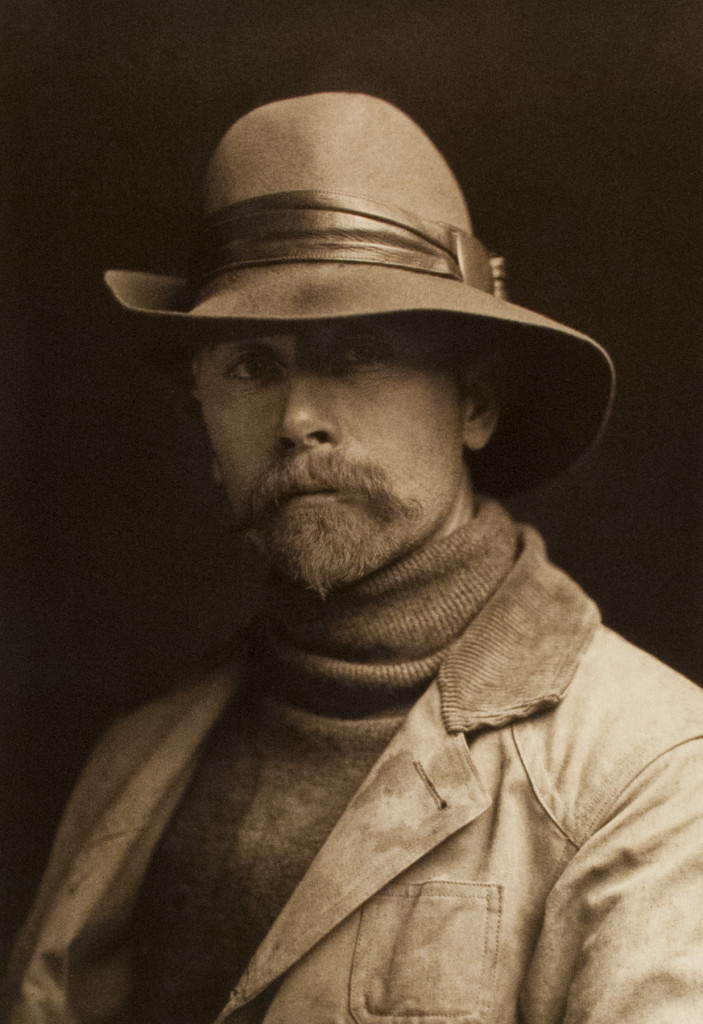

When, at age 32, American photographer Edward S. Curtis set out to urgently document the many rituals and faces of the Native Americans up close and personal, languages had already vanished and most of the land had been seized. Nevertheless, Curtis embarked on a mission he figured would take 10 years. He was 61 when he finished.

A selection of 100 candid photographs depicting majestic landscapes, secret dances, women, children, warriors and chiefs, are now on view at the Flagler Museum through Dec. 31. That sounds like a comprehensive selection, until we learn that Curtis produced nearly 50,000 negatives while documenting 80 tribes between 1900 and 1930. The epic undertaking led to his 20-volume set of handmade books titled The North American Indian and took everything the adventurer had.

Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks is organized by geographic region and features photographs of the Jicarilla, Sioux, Cheyenne, Zuni, Mohave and Piegan tribes, among many others. All the artistic processes the artist employed to record what he perceived as a quickly vanishing culture are also represented, including cyanotype and gold-tone pieces.

If the images appear non-glossy, almost like paintings or drawings, that’s because they are printed on porous, watercolor paper, which has the added benefit of softening the image. Among the most striking in the first room, is a touching sepia portrait of a young girl staring into the camera. She is covered by a dark cloth. There are no markings or adornments that could tell her story. Qahatika Girl shows a subject that is not completely at ease posing, but her firm gaze projects calm and transparence.

Curtis did not sacrifice his artistic voice for truthful reality. The soft, blur edges in Qahatika Girl show up repeatedly throughout the show. Many photographs were manipulated and come across as romantic and idealistic. For instance, The Scout-Apache platinum print from 1906 was shot from downhill making the subject appear to stand above us. As a result, the rider seems more in control and exudes great confidence. In another image titled Vash Gon-Jicarilla (1904), he manipulated the light to get the twin silhouette of the sitter’s illuminated profile on the wall. In this dramatic portrait housed in the second room, the Jicarilla chief sports wrapped braids hanging over his shoulders, beaded earrings and a neck scarf.

A fierce warrior, Red Hawk, wears a full war bonnet with eagle feathers in An Oasis in the Badlands (1905). He sits regally on his bright white horse patiently waiting for the animal to quench its thirst. Both, man and beast, are seemingly unaware of the dark, dramatic clouds forming around them. This is one of many photogravure prints in the show. The process, which requires that the photographic image be chemically etched into the surface of a copper-clad engraving plate, was favored by Curtis for his soft resolution and warm tone.

As early as 1901, Curtis’ pictures were being celebrated for their ethnological value, but unless you are good at detecting patterns in physical features, you have to read the descriptions to know when you are looking at a different tribe.

Judging by the diverse subjects on display, it is clear Curtis’ interest went beyond capturing ethnic traditions and pronounced cheekbones. One striking landscape shot depicts a group of Navaho riders passing through a picturesque Canyon de Chelly, in northeastern Arizona. The tiny horsemen are framed against commanding 1000-foot-high walls. The image speaks to the lasting presence of Nature versus man’s small, temporary role in it. Distinctively powerful, Curtis printed it in at least four different photographic processes.

That unspoken, spiritual connection with the natural surroundings is also seen in a sepia print from 1907 titled The Blanket Weaver. This soothing picture features a Navaho weaver — her back to the camera — working on her craft under the protection of a gigantic ancient tree and a large rock formation hardly discernible. Nature is undisturbed, unbothered by the human presence. It welcomes the female laborer and offers her a beautiful setting where her creativity can flourish.

Curtis first came across Native American culture in 1900 during a trip to Montana. By then, the ambitious married man, who had a sixth-grade education, enjoyed a good reputation as a photographer in Puget Sound. A Seattle newspaper had declared him among the greatest local examples of “business energy and perseverance.”

Exactly how the white, blue-eyed photographer gained the trust of weary tribes already touched by death and starvation and sensing extinction was next, is part of what makes the show magical. It is hard to believe he was allowed to get that close to their women, children and warriors. We are safe to assume that the trust didn’t develop overnight and pursuing it probably involved misunderstandings and close calls.

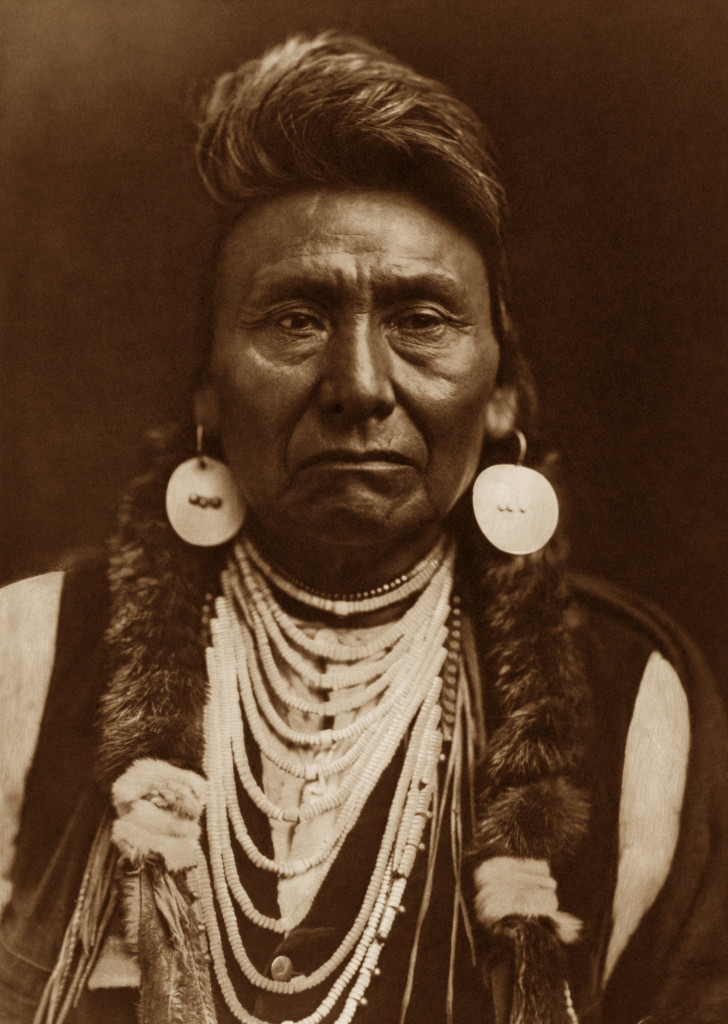

Proof of this unprecedented access is in an eerie 1907 sepia portrait of a Navaho medicine man wearing the horn mask of Ganaskidi, which means hunchback and is the Navaho god of harvest. Among those who vouched for Curtis and aided his access to sacred ceremonies and tribes was the famous Chief Joseph, of the Nez Perce Tribe, who led his people on a failed attempt to escape to Canada to avoid life in captivity on a reservation. He is pictured in a photogravure printed in 1903 standing proud and king-like; almost as if he knew his picture would re-emerge a century later to be admired.

It is fair to note that several photographs in the show, including this one, feature subjects posing rather than in spontaneous positions. Curtis made use of this common practice, as evidenced by his funding request to J.P. Morgan, which included an entry of $1,450 to pay the Indians.

The optimistic and unwavering photographer could not have imagined he would join the sad ranks of masters who died before seeing their lifework recognized. Besides this monumental visual census of Native American tribes, he preserved 10,000 wax cylinder audio recordings and is credited with making the first narrative documentary film. By the time he died in 1952, however, few knew of the man Teddy Roosevelt had described as an “artist and trained observer.” He had no family and no money.

The galleries’ simple setup and muted green walls are the perfect reception for the recently rediscovered works. The dimmed lights might seem a modest introduction for an art that deserves trumpets and fireworks. Then again, when you are magical enough to make a way of life live forever, there is no need for all that jazz.

Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks runs through Dec. 31 at the Flagler Museum, 1 Whitehall Way, Palm Beach. The museum is open from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, and noon until5 p.m. on Sunday. Admission is $18 for adults, $10 for youth ages 13-17, $3 for children ages 6-12, and children under 6 are free. Call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.