Editor’s note: Here are late reviews from three concerts at the Society of the Four Arts. Technical difficulties prevented them from being posted earlier.

Nordwest Deutsche Philharmonic (March 14)

Visiting orchestras often come to our balmy shores this time of year; 20-city tours exhaust the best of them, riding on buses around the Florida peninsula.

It was not so with the Nordwest Deutsche Philharmonic, which after 17 concerts sounded fresh and invigorated in their program at the Four Arts. Based in Herford, Germany, normally a 76-piece symphony, they traveled light and brought only 64 players, which is probably as well since they looked very cramped on the small stage.

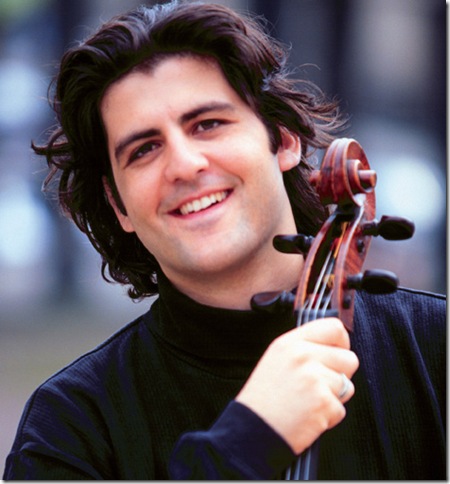

The highlight of their program was Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 (in E flat, Op.107), written in 1959, with Israeli cellist Amit Peled as soloist. It’s a gloomy work, full of brilliant scoring for cello and orchestra. But Stalin’s oppressive rule was ever-present in the music, though he died six years before the concerto was written.

Written for world-renowned cellist and dissident Msistislav Rostropovich, who gave its first performance in Leningrad, it begins with intense solo cello playing of a four-note theme, framed by a hard-working solo horn, with pairs of winds and a piccolo who play a jocular march.

The second movement opens with the string section of the orchestra describing a vast open barren landscape, pierced by a single penetrating anxious horn. Solo cello plays a languid, soulful melody backed by violas. Peled’s mastery of his instrument shone through with great sensitivity and a beautiful tone. Here the music has much darker moments: a searching , questing, mysterious, unresolved ending played double pianissimo that dies away with the cellist and a quiet celeste fading into nothingness.

The third movement is devoted to the soloist, no orchestra. Peled gave us some extremely virtuosic cello playing, brilliant in its interpretation of Shostakovich’s tortured music. In a jazz concert setting, his “set” would have been greeted with a terrific round of applause. Exciting music starts the last movement; this is the Shostakovich we are familiar with, in its driving forward force. The nightmare is over, it seems to be saying. But the fear of oppression lingers, personified by “screams” emitting from the wind instruments in the highest notes of their register.

The original four-note theme returns, happiness creeps in again. A little band is heard off in the distance, marching along as the solo cello has a flurry of virtuosic scales and octaves before the unexpected abrupt ending. Comparisons of Peled to Rostropovich in the program notes miss the mark. Rostropovich was a showman and very flamboyant. Peled’s quiet strength and serious approach , with a fine, long-fingered technique, comes across as sincere, effortless, and unassuming, like the late Pablo Casals, whom I saw and heard as a young man.

Grieg’s incidental music for Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt opened the program. Of the 26 pieces Grieg composed, the conductor chose four – Morning, Ase’s Death, Anitra’s Dance, and In the Hall of the Mountain King. It was obvious this orchestra had a refined quality. Its young American conductor, Eugene Tzigane, shaped the music with a delicate and effective baton technique. However, far too much body movement on the podium made him look quite athletic.

Brahms’s First Symphony (in C minor, Op. 68) ended the evening. The orchestra gave the music the required feeling of majesty with a refreshing attack, disciplined playing and warm musicality. Point-counterpoint, prominent as always in Brahms, was nicely accomplished.

Concertmaster Takahiro Tajima played the solo in the second movement beautifully, and that sensitivity was displayed by the whole orchestra in the third. The finale is what everyone anticipates, with its introduction by the horns of Brahms’ most famous marching song. This whole movement must be one of the best first attempts at orchestration by any composer; it is so rich in its contrasts.

And the Nordwest Deutsche Philharmonic gave it a fine reading, which was met by a well-deserved standing ovation.

David Finckel, Wu Han and Philip Setzer (Feb. 26)

A concert Feb. 26 at the Society of the Four Arts provided an occasion to hear three of the finest instrumentalists of our time: Pianist Wu Han and her cellist husband, David Finckel, and violinist Philip Setzer.

The Finckels are highly esteemed, not least because they are the artistic directors of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in New York. Setzer is a founding member of the Emerson String Quartet, for which Finckel is the cellist.

Sunday’s program was devoted to the music of Felix Mendelssohn, and it opened with his Cello Sonata No. 2 (in D, Op. 58), written in 1843.

The sonata has a lively beginning, with the soaring lyricism and rhythmic energy that reflects the Romantic era so effectively. Indeed, Wu Han’s gorgeous attire of many colors set the spirited tone of the piece and matched her brilliant, colorful playing.

From the start, Finckel played from memory. Sly staccato melodies, pizzicato style, repeat and repeat with interspersions of Romantic cantabile on the cello in the Scherzando. The third movement opens with a series of brilliant arpeggios from the piano answered by a passionate melody from the cello, after which they join together, proceeding to a short pianissimo ending and silence.

The effervescent last movement has each instrument matching the other, measure for measure. In the last 16 bars, Wu Han’s accentuated playing drowned out her husband’s cello.

When shown an early draft of Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio No. 1 (in D minor, Op. 49), pianist Ferdinand Hiller told him that when he lived in Paris he became accustomed to the richness of Liszt’s and Chopin’s writing for piano. That helped persuade Mendelssohn to rework certain passages of his Trio in the new style.

With a new baby in the offing from his wife Cecile and the recent death of his mother, Mendelssohn perhaps reflected these events in the beginning of this trio; one might describe its sounds as “dark joy.”

The second movement has a sweet opening melody passed from violin to cello. The whole effect is like an unbroken song: heavenly, lyrical music, brilliantly played by all three. The scherzo movement harks back to incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, familiar but original, not of that work at all.

By the last movement, it was clearly evident that in her concertante accompaniment Wu Han is among the world’s better pianists. Her playing is mesmerizing. At the end, she jokingly suggested she played far more notes than her colleagues and should be paid by the note.

The Piano Trio No. 2 (in C minor, Op. 66) ended the afternoon. It was a present for his sister Fanny’s birthday, and it begins mysteriously on the piano with a few tortured measures, with some lovely violin and cello harmonies centrally placed.

The piano introduces a new theme that is copied by the cello and repeated constantly. Here one had to marvel at Finckel’s masterly command of his instrument. The second movement, marked Andante, returned us to a Songs Without Words-style layout, pensive in mood and beautiful to hear. Quicksilver playing introduces the third movement, perilously fast (Even Mendelssohn said “it is a trifle nasty to play’’). The last movement is at times stately and lively, with hints of a Lutheran hymn tune and Jewish folk songs.

At its rousing climax the audience stood and cheered the heroic playing they’d just heard, unusual for a crowd that normally takes such event in stride. And they were rewarded with an encore of the final movement of the Piano Trio No. 32 (in A, Hob. XV: 18) of Haydn, which proved to be a delightful lollipop.

Faure Quartet (Feb. 19)

Before the appearance Feb. 19 at the Four Arts of Germany’s Faure Quartet, it was announced that pianist Dirk Mommerz had been hospitalized overnight and had been able to get only two hours’ sleep.

But Mommerz agreed to perform, and the drama of the announcement had the audience sitting on the edge of its seats. Opera companies have substitutes standing by for sudden illnesses. This troupe flew in from Germany the day before with no such luxury.

Understandably a little ragged at first, the quartet moved right into Mendlessohn’s Piano Quartet No. 2 (in F minor, Op. 2), dropping its scheduled opening work, the Piano Quartet of Josef Suk. As the piece progressed, Mommerz played well and even led at times, which reassured an anxious audience. This first movement has lovely piano solos, illumining Mendelssohn’s own keyboard brilliance (he was a concert pianist from age 9); the quartet was written when he was 14, and it was dedicated to his teacher Friedrich Zelter.

Violinist Erika Geldsetzer played vigorously (though her loose ponytail became distracting with every move of her head); her continuous inscrutable smile giving the impression that all was well. Cellist Konstantin Heidrich and violist Sascha Frombling played in a very refined European manner, ardently attentive to their piano colleague’s condition. The violin leads the second movement, as the piano texture blossoms with lush arpeggios played beautifully by Mommerz. The short, sweet third movement leads into a lively and cheeky finale which was played aggressively and with feeling by all four artists.

Cellist Heidrich asked the audience to listen for the quartet’s “symphonic sound’’ when they played the Piano Quartet No. 2 (in E-flat, Op. 87) of Dvorak. A tuneful opening theme of instrumental unisons introduces a few songful romanticisms in the first movement, and ends with tremolo strings passing around a quiet melody before closing.

Heidrich’s refined playing began the second movement and an excellent conversation among the three string players went back and forth with spellbinding beauty. A waltz-like rippling piano opens the third movement, moving into a mazurka played by Frombling : exquisite music, excellently played.

Lots of nervous energy pulled the finale together. The Dvorak key change descending to E-flat major was brutally obvious and nicely achieved by all four players. I would have wished for a stronger sound from violinist Geldsetzer. Pianist Mommerz made it through the program, his good reputation intact. And the near full house, sensing a victory of mind over matter, rose to its feet in grateful appreciation.

Listening intently, I didn’t quite hear the symphonic grandeur, but perhaps it was the devout wish of a worried colleague urging them on after the announcement.