Hailing from a long-line of female ceramicists, Rose B. Simpson grew up in northern Arizona in the Santa Clara Pueblo, (also known as Kha-‘Po Owingeh, or the “Singing Water Village”), a town with a population of fewer than 1,000 residents.

The daughter of renowned sculptor Roxanne Swentzell and metal artist Patrick Simpson, Simpson, 41, is an in-demand contemporary mixed media artist and ceramicist whose work is on display at the Norton Museum of Art, as part of their Recognition of Art by Women (RAW) Exhibition Series, running through Sept 1.

Titled Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay, the exhibition features works by Simpson, her mother, Roxanne Swentzell, her grandmother, Rina Swentzell and her great-grandmother, Rose “Gia” Naranjo, tracing the Indigenous artist’s long, matrilineal line of Tewa artisans.

“We’re thrilled to present ‘Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay’ as part of the RAW series, a continuation of our dedicated work to combating gender disparity in the art world,” says Ghislain d’Humières, the museum’s CEO. “That we can include works from four generations of her family is particularly remarkable.”

“Her emotionally engaging works encourage visitors to look inside themselves and reflect on the human condition,” he says.

The ninth iteration of RAW, which has included exhibits by Austrian painter Svenja Deininger (2017), American artist Nina Chanel Abney (2019) and Colombian visual artist María Berrío (2021), this is the first to recognize art by an Indigenous woman with a solo show.

Descended from 70 generations of potters and ceramicists, Simpson is forging her own way — with an MFA from Rhode Island School of Design and an MA in creative writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts, Simpson is as comfortable wielding a chain saw, chopping an adobe, riding a tractor or tinkering under the hood of her custom low-rider, a 1985 El Camino named “Maria,” as she is in sculpting clay.

The El Camino is named after San Ildefonso Pueblo potter Maria Martinez (who died in 1980), known for her black-on-black ware pottery

A car geek, Simpson replaced the engine and painted the car in Martinez’s style of black-on-black, both matte and glossy, with geometric designs, resembling her iconic pottery. A photograph of the car hangs at the Norton as part of the exhibit while the actual car is currently part of an Indigenous art exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of Art through July.

“Simpson’s works are an exploration of her community and her practice where one thing leads to the next and everything works in concert with each other,” says Arden Sherman, Glenn W. and Cornelia T. Bailey senior curator of contemporary art at the Norton.

Transmitting her maternal ancestral knowledge, Simpson utilizes found objects, mechanical hardware and even old car parts to explore issues of womanhood, family, gender identity, cultural stereotypes and living in a post-colonial world.

“Indigenous women (like myself) are living in a post-colonial stress environment,” she says.

Much of her work is adorned with symbols representing a visual language offering guidance, direction and protection. Curtains with these symbols mark the entrance to the exhibit providing a space to stop think and reflect before entering.

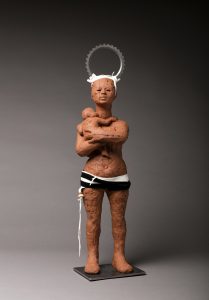

Created with a technique she calls “slap-slab,” which embraces imperfection, Simpson’s ceramics vary in scale, from her Ancestors series of 19-inch hanging masks to larger-than-life-sized figurative sculptures, such as Great Lengths, one of her earlier pieces, a 9-and-a-half-foot-tall figure carrying a ladder on its back.

Her “storyteller” figure (a common depiction in Indigenous culture), usually an open-mouthed figure surrounded by smaller figurines of children, animals, or both, that listen to the storyteller, descends from a long-line of storyteller objects.

In Simpson’s representation, the larger mother figure is adorned with smaller figures set inside a cage-like structure, which Simpson says is both “restrictive and supportive.”

Also on view are life-sized mixed media and ceramic pieces, such as Genesis, a sculpture of a haloed woman holding a small child, and Cairn, a female figure bisected by a sphere with protective markings covering her body.

Additionally, Roxanne Swentzell’s ceramic figures of seated mothers holding babies and Rina Swentzell and Naranjo’s small, ceramic vases are on display, showcasing the traditional Pueblo style of pottery.

Simpson is interested in the way we move through the world, encouraging viewers to be more considerate of themselves and the world around them.

“I’m excited about ‘Journeys of Clay’ and the RAW residency because it is important to me to show the context surrounding my work; my great-grandmother was a risk-taker, a trait that has been passed down for generations,” says Simpson.

“My mom has pushed through so many boundaries, stereotypes and expectations,” she says. “These women have helped me to do the work that I’m able to; they have showed me how to be brave.”

There may soon be another descendant in that long line of matrilineal ceramicists as Simpson’s daughter, Cedar, now 7, already shows an interest in fashion, creating and experimenting with applied aesthetics.

Since the birth of her daughter, Simpson sees a shift in herself to becoming more responsible, accountable and loving. Having her daughter has made her look more deeply into herself and to value a new-found sense of power which is less aggressive and self-contained.

Before Cedar, Simpson said she had “more going on,” whereas, now she says “more is going in,” as she reflects more of her internal experiences.

“I want to pass along the gift that you can be creative and use your art to sustain yourself creatively, spiritually as well as financially,” she says. “Go where it’s uncomfortable and challenge expectations to deconstruct a new reality.”

Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay runs through Sept. 1. Visit the Museum’s website at norton.org or see them on Instagram and Facebook. The Norton Museum is located at 1450 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach. Call 561-832-5196.