By Márcio Bezerra

As the most prestigious musical institution in the Southeast, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra needs no introduction. For 78 years, the orchestra has established itself as a major American ensemble and one hopes that, under the new leadership of Music Director Nathalie Stuzmann, it will be able to expand its musical horizons by featuring a more varied repertoire as well as younger faces as guest artists.

If the concert presented by the venerable ensemble at the Kravis Center on Jan. 13 is an indication, the orchestra is on the right path of fulfilling one’s most ambitious hopes.

Directed by young American conductor Kazem Abdullah, the Atlanta Symphony delivered an exciting performance that had the right mix of well-known and more obscure works.

Case in point was the opening Overture No. 2 (in E-flat major, Op. 24) by Louise Farrenc. A Frenchwoman whose career was focused on piano teaching and performing — she held the prestigious post of professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire for 30 years — her compositions have been receiving attention lately thanks to the new interest in music by women and other less represented groups.

The overture, written in 1834, is a standalone work that features competent orchestral writing and a rhythmic effervescence that reminds one of Rossini. Abdullah made a strong case for adding Farrenc’s music to the canon. His swift choice of tempi was negotiated with ease by the musicians and he balanced the orchestral sections remarkably well. It was a very satisfying opener to a very satisfying program.

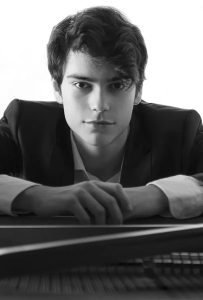

The orchestra was joined by Israeli pianist Tom Borrow for Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 (in G major, Op. 58). Written in 1805 and dedicated to Beethoven’s friend and major patron Archduke Rudolf, the concerto is very different in character from its more heroic companions (Nos. 3 and 5). Full of dreamlike moments, the work starts with a piano solo and looks back to Mozartean delicacy and pearly sound, although with expanded emotional range and technical demands.

Borrow displayed a shimmering touch and handled without effort the many technical difficulties in the first movement. His cadenza was particularly effective, featuring the right amount of rubato to simulate an improvisation.

His lyrical approach to the second movement was also convincing, although he could have stressed the more dramatic aspects in the trill section. In the third movement, he played the difficult passagework with bravura, his only flaw was the tentative performance of the two cadenza-like scales that precede returns of the rondo’s main theme.

At 22 years of age, Borrow has a bright musical future ahead of him and the Atlanta Symphony is to be commended for providing the opportunity for young talent to shine.

The second half of the program, dedicated to the music of the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, brought the same felicitous blend of well-known and more obscure works.

The ever -so-popular Finlandia (Op. 26) received a brisk reading, again highlighting Abdullah’s fine sense of balance and the orchestra’s technical virtuosity. A little less rushed tempo, however, would have made the work sound more heroic, especially in its apotheotic ending.

Valse triste (Op. 44, No. 13) followed, again displaying the excellence of the Atlanta Symphony and Abdullah’s finesse in negotiating tricky tempo changes and rubati.

The main work on the program followed: Sibelius’ Symphony No. 7 (in C Major, Op. 105). His last and a less well-known work in the genre, it was finished in 1924 and it is a rather unusual take on the symphonic genre.

Consisting of one movement, the symphony has no easily memorable melodies, but it is constructed in a very original way that requires close listening. Its four main sections, mirroring the four movements of a symphony, succeed each other seamlessly and without much development, suggesting to some the stillness of Finland’s remote countryside.

Again, Abdullah led the Georgian ensemble with finesse, preparing climaxes with precision and negotiating tempo changes with ease. Unfortunately, the underwhelming ending of the symphony did not lead to extended applause and the Atlanta Symphony, despite providing an outstanding evening of music-making at the Kravis Center, left the stage without performing an encore.

Had Finlandia been featured at the end of the program, the story would be much different.