Like a giant slap in the face, the new Pop Art exhibition at the Boca Museum of Art wakes us up from a long hibernation filled with compulsive consumerism habits, celebrity infatuation and overindulgence. The effect, however, is momentary.

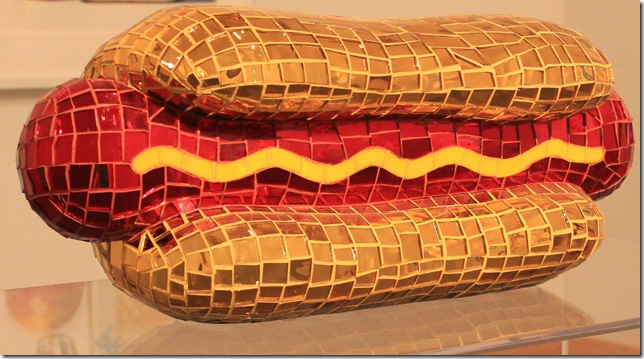

It may not be enough to change our ways, but faced with a giant hot dog made of mosaics, a thought does come to mind: How did we get to this point? And what does it mean that art, for a while now, can be this? We in America must be in the final stages of a really bad disease.

Jean Wells’ Hot Dog (2010) even features a line of mustard achieved with 19 shiny pieces of glass carefully arranged. The bright colors make it appear playful, and no doubt this work is visually striking, but the size and reflective quality of it speak about something more serious: the volume of our consumerist appetite.

Pop Culture: Selections from the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation uses the entire first floor of the museum, and four months of the year, to explore the origins of the Pop Art movement and its continuing influence on contemporary art. More than 100 works are included in the show running through April 23. Among the artists represented are Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, Edward Ruscha and Keith Haring.

A print titled Corn Bred (2010), by Grissel Giuliano, targets our relationship with food. A dried ear of corn sits, exposed, on top of an ornate white doily. Six teeth appear atop the kennels. At first they look like fresh slices of banana but the glossy quality to them and white coloration is distinct. The clean setup suggests sophistication, although the addition of the teeth is a bit morbid. A written description explains the work might suggest we are what we eat.

John Waters is known for his avant-garde films (Hairspray) but here we meet Waters the visual artist through Hungry Hamburger (2000). The work consists of 10 chromogenic prints arranged like a horizontal filmstrip. From right to left, we see bites taken from a hamburger that started whole but is slowly disappearing with each slide. Only bread crumbs are left in the end.

Below Hamburger appears a dotted insanity by Japanese-American artist Yayoi Kusama. Pumpkins (1982) features 20 ceramic pumpkins sitting inside wooden boxes in rows of five. They are covered with Kusama’s recognizable dots. Most of their bodies are painted yellow with black dots while the black sections spot yellow dots. Kusama is known for these controlled repetitions she calls “obsessions.”

Here, too, we find a watercolor piece titled Cubo con Agua (2000); translated from the Spanish it means “bucket with water.” In the image, everyday workers’ tools, such as wooden rulers, are piled inside a gray metal bucket. It is not among the most striking works on display, but it is something you do not see everyday in that it does not credit one artist but several. Originally a trio, Los Carpinteros (The Carpenters) are a group of young Cuban artists who live and work in Havana and reject the notion of individual authorship.

When it emerged in the mid-1950s and 1960s, the Pop Art movement sought to sarcastically and ironically emphasize images of elements of mass culture and consumerism. The artists participating in it ignored traditional subject matters and instead used everyday objects, popular culture and mass media as inspiration. A pop artwork was to be elevated as high as fine art and shared by all people regardless of class and artistic skill. Art was never the same.

Works in series now replaced the single unique original work of art. Critics believed that Pop artists were simply copying the works of commercial artists. Frankly, some do look like copies. Others saw it as a continuation of Dada because it embraced and encouraged the use, and reproduction of, everyday objects. Think Marcel Duchamp and his ready-mades. While some Pop Art works celebrated consumer products and celebrities, others took a more critical approach to mass consumerism.

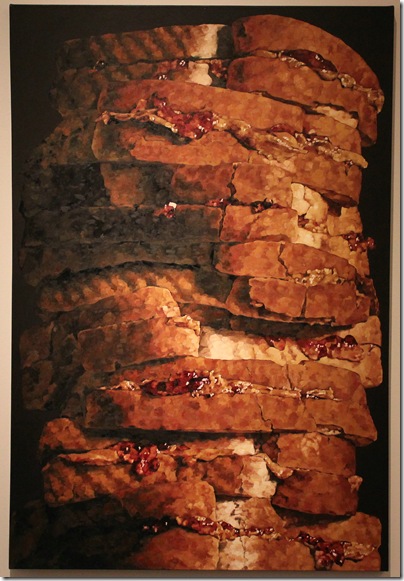

Take the three works on display by Pamela Michelle Johnson: Pop Tarts, Hostess Cupcakes and PB & J. The realism and size of the paintings force us to look at the dark side of abundance and overindulgence. In one, Pop-Tarts appear stacked up until they get cut off by the canvas as if suggesting that our appetite is endless and cannot be contained. Next to it appears an array of cupcakes. As opposed to the Pop-Tarts, several have been bitten into and left half eaten. On those, the creamy white middle is visible and should look inviting, but it seems repulsive.

A tower of peanut butter sandwiches of dark and light crusts follows. Jelly is seen dripping out of some while in others the crust is cracking. This tower is crumbling. If only we had not ignored the consequences of excess, the artist tells us.

A waterfall of candy wraps greets us from the glass windows separating the south and north sections of the exhibit. The 20 strings holding a multitude of candy wraps of all colors and flavors is a work by New York-based artist Luisa Caldwell. It easily brings a smile to those who see them, whether or not they agree with the artist’s message of consumption, wastefulness and abundance.

If the highway billboards sporting faceless physical female attributes ever gets you upset, stay away from Tom Wesselmann’s large-scale cutouts of female body parts. Wesselmann is best known for his Great American Nude series.

Here we get images of mass-consumer female eroticism without a body or a context. In Mouth No. 6 an irregular shaped canvas features the profile of an open mouth. The voluminous lips, with glimpses of the front teeth, are the only thing visible.

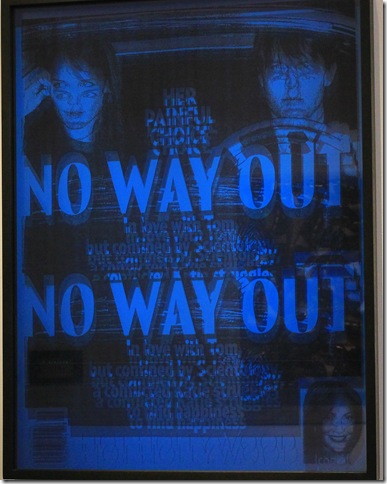

In No Way Out (2007), by Paul Rusconi, we see a magazine cover with Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes. It reads: In love with Tom but confined by Scientology. A digital screen is used to project an image on the photograph. Until then, there is no image on the actual photograph. The work, featuring a vibrant blue background, speaks to our thirst for fame as well as social identification and personal projection.

Instead of comforting us or softening our self-destructive behavior with an absolving It’s not you, it’s me message, the works in Pop Culture keep telling us: It is all you. But we do get breaks to our conscience here and there.

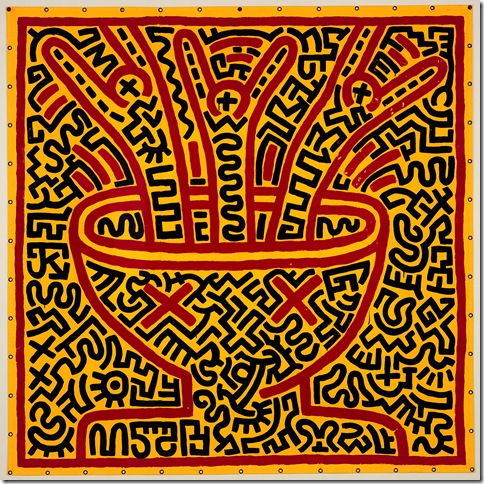

An untitled 1983 work transports us to the playful land of Keith Haring, where silly designs rendered in bold lines and bright colors paint a lively, innocent picture. Here three figures defined by bold red lines emerge from a fountain with great enthusiasm. Their arms are up in the air and a plus sign serves as their faces. The rest of the painting is filled with wormy-like linear patterns, arrows, Xs.

Crushed Orange (1980) is an interesting take on photo-realism by Puerto Rican artist Jose Luis Quiñones, who, unlike other photo realists, preferred brushwork over airbrushing. Notice the irregular shape of the canvas, with sharp edges sticking out. Quiñones wanted to preserve the contours of the crushed, flattened soda can.

Vincent Szarek brings us sleek aesthetics and industrial perfectionism with his Black Cherries (2013). Szarek’s experience working in auto body and custom shops comes across in the finishing touches of the piece: high gloss and gold-plated components.

But the perfect photo op is offered by Indian 2 (Bowman) by Israeli-born Yoram Wolberger. A red man stands ready to fire. The borders have been left uncut. A recognizable plastic toy is brought to life-size to question the influence of these objects in our childhood. Think of this as you pose at the other end of his arrow.

You probably have found yourself in a conversation about traveling, ethnicity or culture and wondered what exactly America stands for. Think of Italy and perhaps pasta comes to mind. Think of France and you visualize stripped T-shirts and berets, maybe wine. Now think of America. The pictures in your mind should look a lot like Pop Culture.

Having walked the entire first floor, except for the auditorium where French and Japanese prints are being shown in a separate exhibition, I started thinking about Pop Art’s own self-destructive tendency.

If the message, as I have read again and again, is to confront us with our self-destructive habits, what is Pop Art if not a suicidal movement? What if, faced with the amplified images of everything toxic that we love and pursue (fame, food, soda cans), we were to walk away changed men and women? What if we all turned minimalist, consumed only the very basic necessities and ate just enough veggies and fruits? What would happen to the subject matter that Pop Art depends on to exist?

Would Pop Art die or begin generating blown-up images of a carrot? Instead of commenting on the harmful instant gratification mentality, its message would be about America’s obsession with balance, moderation and patience. And this would be a show about the happiness experienced by all, not about our insecurities and dissatisfaction.

Instead of Marilyn Monroe, maybe we would get the Dalai Lama.

Or it could be that Pop Art as a movement has never had faith in humanity and it knows, even when confronted with crystal-clear evidence of cultural and social decadence, we, humans would do what we do best: Yawn.

After some minutes pondering this idea, I headed out. I was starving and the giant green Exclamation Point created by Richard Artschwager, which aims to amplify the viewer’s emotion, was doing just that: amplifying my hunger.

I stopped by the first fast-food place I could find and devoured a hamburger. It tasted sweeter than ever.

A piece of advice: do not come to the exhibit hungry.

Pop Culture: Selections from the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation runs through April 23 at the Boca Raton Museum of Art. Admission: $8 adults, $6 seniors, $4 students. Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesday, Thursday and Friday; 10 am-8 pm first Wednesday of the month; 12 pm-5 pm Saturday and Sunday. Closed Mondays and holidays. Call 561-392-2500, or visit www.bocamuseum.org.