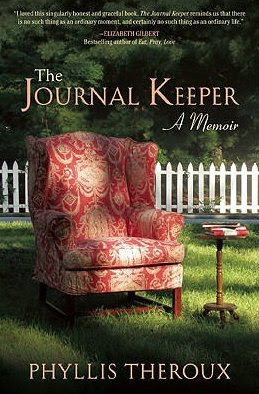

The Journal Keeper: A Memoir, by Phyllis Theroux

(Atlantic Monthly Press, 279 pp., $24)

By Bill Williams

Phyllis Theroux offers readers a gift by letting us peek into the journals she kept during six years of her life beginning at age 61.

The Journal Keeper excels on several levels – for the pure enjoyment of Theroux’s evocative writing, as a tribute to the art of journal writing, and as a meditation on life, love and death.

Aspiring writers would do well to study Theroux. Her gorgeous prose seduces the reader, who may feel compelled to grab a friend and read passages aloud. She describes writing as “laboring long hours to buckle words around an idea and make a sentence slide across the page like Fred Astaire across a dance floor.”

The book consists of six chapters covering the years 2000 to 2005, and includes background notes to give context to the entries.

Like most polished writers, Theroux is a voracious reader. She savors books by Thomas Merton, Harper Lee, Karen Armstrong and especially the poet Mary Oliver. Reading Mary Oliver “enables me to write a few good lines from a place I hadn’t found before. Poetry excavates, blasts, cuts through the flab.”

Theroux has a poet’s eye for detail. Sitting in a friend’s kitchen, “I was aware of how the air in her house has the thick flavor of dust, sunlight, old books, fried chicken, and furniture polish.”

We learn at the start that Theroux is divorced and lives in Virginia with her aging mother, a “high school dropout Buddhist transcendentalist” who listens to spiritual tapes, meditates and does yoga exercises. When her mother dies suddenly, Theroux experiences mixed feelings “but primarily gratitude that she had been with me for so long.”

The author worries about aging, meditates on impermanence and wonders if she is a good enough writer: “I feel at the age of 61 that I should be a sage, not a novice. It is embarrassing to be so shallow.”

But there is nothing shallow about Theroux’s writing and wisdom. Consider this nugget about humility. “It suddenly struck me that true enlightenment consists in being empty, not full, of answers, that people who are full of answers must drag them around all day like an over-packed suitcase, with no room for anything new.”

Theroux wonders if she is captive to writing and imagines “how it would be to let go of writing, to lose my grip on the chain of words that leads me through the darkness. Am I not a prisoner of words, dependent on them in a way that tethers me to my own intellect?”

When friends die, Theroux reflects deeply on life and death, finding that “a funeral is like a train station waiting room. We’re all going to board the train someday.” Occasionally, Theroux longs “to be 30 again, surrounded by other 30-year-olds who are so bright, clever and beautiful.”

After the death of her mother, the author cherishes her life alone, while conceding that she misses the affections of a male lover. Dealing with ambiguity, she reminds herself that “one’s happiness and worth must come from within.”

And yet out of curiosity she decides to sign up with Match.com. After her initial matches do not go well, she is “faced with the truth that I am not a sex object.” But then she meets Ragan Phillips, who is “tall, bubbly and smart,” and three years older. They fall in love, then break it off, and finally get back together and marry.

“The unfamiliar, unexpected security of having a partner washes over me, changes the landscape the way flowers do,” she writes. “After being alone for most of my life, I cannot quite believe that I’m being given a companion with whom to end my days.”

Those who keep a journal may be inspired anew by this book, and those unfamiliar with the practice may want to begin. Theroux has filled at least three dozen journals over the years. She includes a couple of pages of advice at the end of The Journal Keeper. I wish she had said more.

“Your journal,” she writes, “should be a wise friend who helps you create your own enlightenment. Chose what you think has some merit or lasting value, so that when you reread your journal in years to come, it continues to nourish you.”

Bill Williams is a freelance writer in West Hartford, Conn., and a former editorial writer for The Hartford Courant. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.