Retrospective exhibits excite because they allow enthusiasts to witness an artist’s evolution. Rememberingstanleyboxer: A Retrospective 1946-2000, currently on view at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, is no exception.

The 50 works, mostly paintings, but with a few sculptures speckling the landscape, tell the story of Stanley Boxer’s progressive love affair with abstraction. It’s a love affair that crescendos with brilliance and whimsy, thought the journey upwards is tempered and deliberate.

Wall text and catalog essays notwithstanding, this exhibit speaks for itself. Stand in the center of the gallery and read it as you would a novel. Beginning with his early works from the late 1940s and through to the late 1970s, Boxer’s styles reflect the trends of the day. Perhaps this is why he referred to himself not as a painter, but as a “practitioner.”

He latches on to the dominant style and perfects it through practice, creating paintings of skill and observation, though they leave one wondering about Boxer’s predilection to risk-taking. In his early career, he seems inclined to dip his toe rather than dive into the deep end.

Boxer’s art training began after he left the Navy at the end of World War II. He studied on the G.I. Bill at the Art Student’s League in New York, alongside Helen Frankenthaler and Robert Rauschenberg, who became a lifelong friend. Though he worked in other media, including sculpture and printmaking, painting proved to be his foremost passion. By 1953, Boxer had his first one-man exhibit and was represented by the prestigious Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

Early on, Boxer (1926-2000) moves quickly from the figurative to the abstract, as in Bathers (1947), where the colors and shapes allude to the human form and to the sea, with references to Cézanne and Picasso. In his two Figures in an Interior (1957 and 1958), Boxer further pushes away from order and composition by incorporating bold, expressionistic brushwork. While not entirely original in gestural style, it is original in its bold use of discordant blocks of color that seem more like cutouts than painted images.

By 1966, and seemingly to coincide with the advent of minimalism, he pulls back from the use of emotional brushwork and strong color in favor of a more subdued palette. The result is a focus on surface that is evident by transparency of the linen on which he paints as well as areas where the surface moves to the forefront because it is intentionally left blank.

This surface and flatness is evident in Two Bathers (1966) and here the cutout images alluded to earlier are real. Elements of minimalism and color field present themselves (though Boxer rejected being referred to as a color field painter by Clement Greenberg).

In the 1972 painting Willowsnowpond, Boxer’s minimalistic approach is most pronounced. It almost seems that he is stifling the passion that once drove his brush in order to succumb to the fashion of the day. However, at this time, his titles become enigmatic collages of words.

“Boxer spoke several languages and he was a voracious reader,” said Wendy Blazier, the Boca museum’s chief curator. “His canvases often had mile-long titles, inventive formations of compound words which would indicate a mood or feeling for the work. Boxer liked to play with these run-on words, sometimes translating his titles into German, because he liked the way the German language linked words together.”

Towards the end of the 70s gesture and brushstroke re-emerge, though at first shyly, as evident in Gleedtwistofflayeddanknessassunder (1978). On the circumference of this work one can witness the moment when Boxer begins to approach painting from a different angle altogether. The paint rises from the surface and bleeds out onto the edges. It wants to break free from the canvas, yet it still restrains itself in a sort of half-in, half-out manner. At this point, it seems so like Boxer to test the waters before plunging in, which he would eventually do with great vigor, and which would become his signature.

“Boxer was often called a ‘sculptor of paint’ for his thickly brushed abstract paintings,” Blazier said. “In the later work from the late 1970s and on, he became known for troweling on pigment, using his fingers, brushes and a palette knife to create textures and patterns that sometimes intimated landscape, but more and more stepped out into the realm of pure abstraction — fields of texture, shapes and riotous color.”

This sculptural quality of Boxer’s work emerges with full intensity by 1980 in works such as Dourspreadofweavingnightglances, (1980). Here paint leaps from the surface and the absence of bold color makes the shape of each brushstroke, each dollop of oil paint, all the more intriguing in its formation. Art critic Grace Glueck once wrote that Boxer’s paintings “…seem to exist purely in the realm of paint: the artist sensuously exploring its physical possibilities without script or program.”

Like a skydiving senior, Boxer’s work surprises most towards the end of his career where it seems that having practiced to perfection, and built a sound reputation, he’s fully confident to take risks. As such, his later paintings morph into a whimsical hybrid of painting and sculpture. He incorporates various materials – wood chips, wood shavings, pebbles, glitter – to compose works of striking contrasts. They are dark, yet colorful. Simple, yet bold.

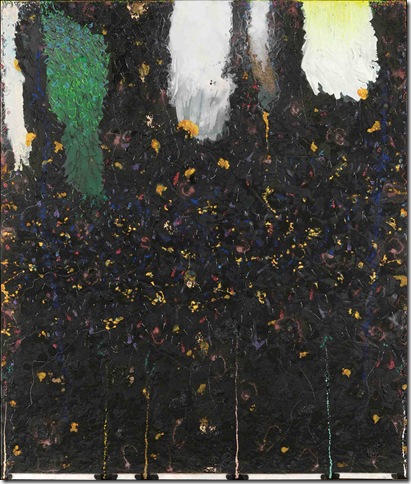

Boxer switches from painting on linen to building on canvas – a sturdier backdrop for what become complex assemblages. Though seemingly sparse from a distance, such as Roilypeersamongbloomednights (1991), these later works have layers of paint and materials. Here, rectangular squares of marble jut out from the bottom of the canvas alluding to Boxer’s sculptures, which are always composed of natural materials such as wood and marble. Yet it still retains its identity as a painted work, featuring a dark black background with yellow and sweeping strokes of white and green.

It’s in the works from the late ’80s and ’90s where elements of all Boxer’s previous styles join together and culminate. “I have deliberately made a practice of being ‘visionless’… that is, I go where my preceding art takes me,” Boxer once said.

This exhibit is an apt chronicle of his journey.

Jenifer A. Vogt is a marketing communications professional and resident of Boca Raton. She’s been enamored with American painting for the past 20 years. She received her B.A. in art history from Purchase College.

Rememberingstanleyboxer: A Retrospective 1946-2000 is on view at the Boca Raton Museum of Art until June 13. Hours for this exhibition are Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Admission is $8 for adults, $6 for seniors, and $4 for students. For more information, call 561-392-2500 or visit www.bocamuseum.org.