By Dennis Rooney

Two staples of the classical repertoire were heard on the final weekend of October at Lynn Conservatory’s Wold Performing Arts Center auditorium, with the students of the Lynn Philharmonia under the direction of the conservatory’s director, Jon Robertson.

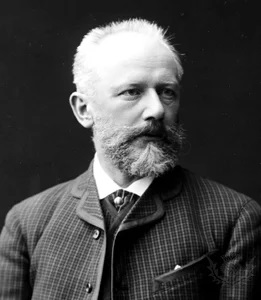

Faculty member Lisa Leonard was soloist in the Piano Concerto No. 1 (in D minor, Op. 15) by Johannes Brahms, which was followed on the concert’s second half by the Symphony No. 5 (in E minor, Op. 64) by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

The concert was a model of its kind. In reviewing the first Philharmonia concert of this season, I chided conductor Guillermo Figueroa for indulging in redundant prefatory remarks. Robertson didn’t feel the need for such indulgence, proceeding directly from the wings to the podium, and then giving the downbeat. This time, my complaint is addressed to the Wold’s house manager. Why even print a program booklet when you don’t bring up the house lights enough for them to be easily read? Or, for that matter, ensure that the many elderly patrons can find their seats without having to peer at the unreadable row and seat numbers in such dim light.

The Brahms was a moderate performance. The first movement is marked Maestoso, which does not indicate tempo. I prefer a tauter approach in this movement, but Leonard and Robertson seemed in perfect agreement, offering a performance that hewed closer to the comfortable than heaven-storming. Occasionally impressive brass and wind playing did not disguise the backwardness of the divided violins in some crucial tutti passages, or much weak intonation, from cellos not in tune with the piano after its first entrance to the thoroughly dismaying cacophony of the closing D major wind chord that ends the Adagio.

Leonard made her best showing in the Allegro non troppo finale, a Rondo inspired by a similar finale in Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto, and in Brahms’s emulation, humor and scholasticism co-exist to advantage.

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 has an “idée fixe” (or motto theme) throughout its four movements. It is announced at the outset by two clarinets, the “beat” between the slightly differing pitches of the two players lending a mysterious, slightly unsettling quality to their duet. The idée fixe is then heard in various guises in each of the succeeding movements. The second subject of the movement is one of the composer’s loveliest melodies.

In the horn solo that begins the Andante cantabile, the player hit a couple of clams at the beginning but then negotiated the remainder quite well. The principal melody (one that had a certain vogue 60 years ago as “I’ve Come of Age” in a Johnny Mathis recording) was as effective as always without any words.

Music students and orchestral players, too, love to invent words to accompany famous melodies, but they favor those that are rude, humorous, and frequently obscene. The waltz that opens the Allegro moderato has a fine set, (unprinted here) familiar to anyone who attended Juilliard or Curtis, not to mention Marlboro, Meadowmount, or Interlochen. Some excellent interplay among the woodwinds and strings highlighted the performance.

As is the current custom, the Andante maestoso finale was performed complete. Our podium ancestors, however, often made a cut of about 70 measures in the development, excising some noisy and rather crude pages that Tchaikovsky himself omitted when he conducted the premiere of the work in Hamburg. It’s a tradition that should be brought back. Throughout the symphony, Robertson led his players expertly. Intonation, so haphazard in the Brahms, was much improved in the Tchaikovsky, and the audience applauded it conclusion enthusiastically.