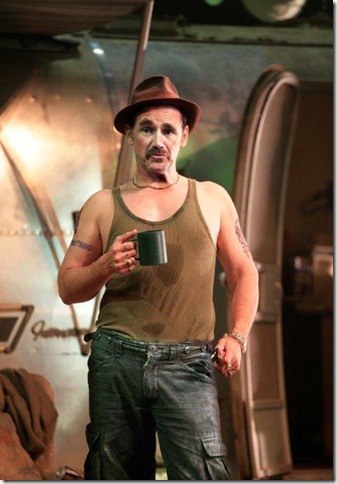

Mark Rylance may just be the best actor working in the theater today.

You might agree if you saw Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem, a powerful, but somewhat overwritten three-hour marathon drama about an iconoclastic former daredevil stunt rider and occasional drug dealer who rails against the world.

Rylance originated the role of Johnny “Rooster” Byron at the Royal Court Theatre in London, where he won every award in sight for his performance and there is reason to think he will do the same over here.

He, of course, won a Tony Award already a few years ago for elevating the farce Boeing-Boeing — no small feat — and again sent critics to their thesauruses earlier this season to find ways to praise his supporting work in the modern verse satire, La Bete.

I did not see either of those productions, but I first encountered Rylance about eight years ago playing the role of Viola in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night at the Globe Theatre in London, where he served as artistic director for 10 years from 1996 to 2006. The production was cast as The Bard would have — all roles played by men — and Rylance’s performance as the young shipwrecked heroine had not an ounce of camp or irony, but was virtually kabuki in its feminine delicacy and authenticity.

Which is to say it had absolutely nothing in common with his “Rooster” Byron. The two roles are simply the most astonishing display of performance versatility I have ever seen. If there is time this week, I’m going to try to see his Boeing-Boeing performance at the Lincoln Center Library’s performing arts video collection and am determined to see whatever he does onstage in the future.

* * *

Stars can often elevate the material they are in, but even the terrific Donna Murphy can do little to help the new musical, The People in the Picture, a mawkish little show that so wants to leave us in puddles of tears, but never bothers to earn the emotional responses it seeks.

I saw the show Wednesday afternoon at one of its final previews, where there were certainly some audience sniffles evoked, but not from yours truly, and I am an easy crier.

Murphy plays a Jewish stage actress in Warsaw, Poland, just before and during World War II, and then as a grandmother in the United States, where she is frail and starting to drift into dementia. Of course, with the switch of a wig and a change of posture and dialect, she keeps bouncing back and forth in time.

The problem is the show wants to be about Holocaust remembrance, Jewish identity and survival instinct, but it conveys those complex subjects with button-pushing shorthand that grates. Nor does it help that the lyrics (and book) by Iris Rainer Dart (who wrote the novel Beaches) are painfully predictable when they are not merely clunky.

Murphy acquits herself well enough, but other talented performers like Chip Zien, Lewis J. Stadlen and Joyce Van Patten are distressingly underutilized. When The People in the Picture opens this evening, it will be the official last show of the season, an unfortunate end to a year with numerous high points.