By Robert Croan

The splendid Chameleon Musicians ended the first season in their new venue in the Broward Center’s pleasant Abdo Room on April 29 with an intense, serious-minded all-Brahms program.

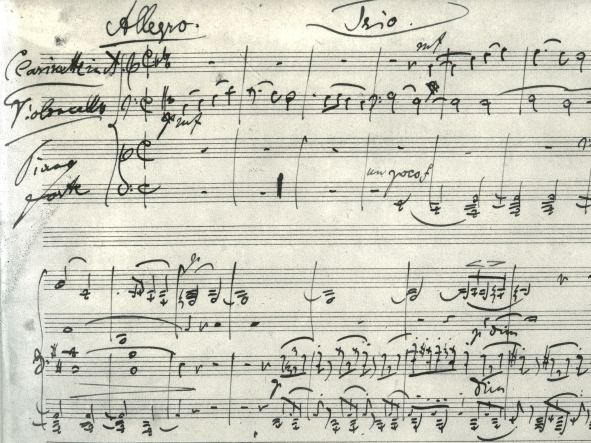

With cellist and Chameleon founder Iris Van Eck joined by pianist Kemal Gekic and Michael Klotz (who alternated between violin and viola), the ensemble contrasted Brahms’s effusive early Trio in B Major for violin, cello and piano (Op. 8) with one of the composer’s last compositions, his introspective Trio in A minor for viola, cello and piano (Op. 114). The latter is an alternate version of the more familiar trio with clarinet – the viola an authorized substitution which its first publisher included to help increase sales.

The concert opened with Brahms’s Sonata Movement for violin and piano – an odd piece composed in 1853 as part of a collaborative sonata to celebrate the birthday of then superstar violinist Joseph Joachim. The other composers who contributed to this “F-A-E Sonata” (so-named for its recurring thematic motif) were Schumann, and Schumann’s student Albert Dietrich. Brahms provided the Scherzo movement, a pleasant but insignificant morsel that served as a warm-up for Klotz and Gekic. Klotz is better known to this series’ attendees as a violist. On this occasion, his violin playing was strident and less than commanding, though he and the pianist dug into the piece with infectious enthusiasm.

In his time, Brahms was considered an ultra-conservative composer. He followed the model of Beethoven, using classical forms though expanding them in the effusive manner of the Romantic era. Uniquely among his peers, however, Brahms favored the sonorities of the lower and lower-middle range of the instruments, emphasized by thick, closely spaced chords, which gives his music a dark, brooding character that is instantly recognizable. This can be quite gorgeous, but an entire afternoon of Brahms can be heavy going. Some bits of brightness and optimism would have been welcome.

What made the event ultimately so rewarding was the way these players communicated – as they always do at Chameleon concerts – their love and joy of playing together. It was like being at someone’s home and listening to old friends (who just happen to be experts on their respective instruments) get together. They interacted in conversational exchanges of phrases, in following each other’s’ subtleties of color and nuance, in an all-over unanimity of purpose that was quite remarkable.

The Trio in B Major dates from 1854, when the composer was 20 years old, wildly Romantic (in the musical sense) and unrestrained in his outpouring of emotion. The Trio contained intermittent mini-cadenzas, ostensibly intended to accommodate violinist Joachim. Later in life, Brahms revised the work, trimming out what he considered the excesses of youth, yet the later version retains much of the ardor and enthusiasm.

The Chameleon performers made much of the lovely arch of the opening phrases, richly stated and reinforced by Gekic’s resilient, rhythmically decisive keyboard work – a major asset throughout the afternoon. The Scherzo was notable for the lilt of the waltz theme midway, while the Adagio abounded with hymn-like piano chords answered by the strings – all the more enhanced by the rich and forceful tone of Van Eck’s cello.

It was enlightening to hear the Op.114 in its permutation for viola, which merges into the collective sound more easily than the soloistic clarinet. And Klotz came into his own, far more impressive and satisfying on this instrument than the violin. This is an inward looking, contemplative work, in which the exchanges between cello and viola set the mood. The similarities in timbre between the two stringed instruments underline the deep-voiced isolation that emanates from this score.

Amid the pervasive gloom, several details, such as the rippling bits of light from the piano in the Andantino, were particularly ingratiating.