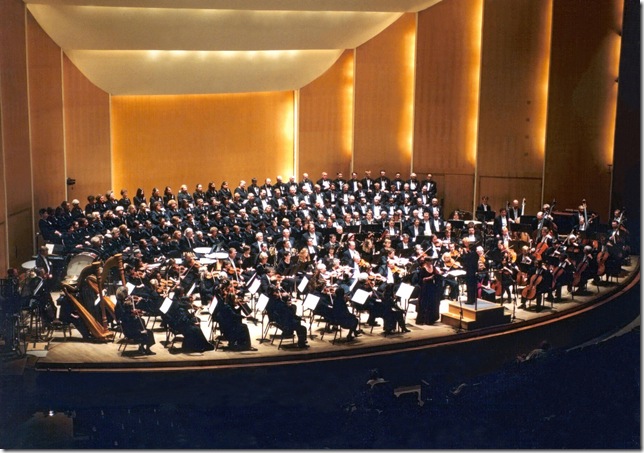

Although it has had eminent leaders in the past, these days the name of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra is indelibly associated with that of its current director, JoAnn Falletta.

It’s not just that, along with Marin Alsop, she is one of the top two female conductors in the country. It’s also that she’s a tireless seeker-out of new repertoire, and has the discography to prove it, most recently recording music of Russian composer Reinhold Glière with the Buffaloans and of 19th-century Boston School composer John Knowles Paine with the Ulster Orchestra of Northern Ireland.

She’s also championed the music of a completely obscure Austrian, Marcel Tyberg (pronounced TEE-berg). An epigone of Mahler and Bruckner who was lost to the Holocaust in 1944, he left his music for safekeeping with a devoted student who, as an elderly Buffaloan, brought shopping bags full of Tyberg’s scores to Falletta. She and the Buffalo have recorded two of Tyberg’s three symphonies (Nos. 2 and 3) and will soon record No. 1.

The quest for fresh music to play is solidly rooted in the history of the upstate New York orchestra, she said.

“In Buffalo, it comes out of a tradition of new and unusual music that began with Lukas Foss and Michael Tilson Thomas, my predecessors here. They laid the groundwork,” Falletta said by phone last week. “… We’re not just a beautiful museum, but a place where we can hear what’s happening now, and what’s groundbreaking. And the community is on board with us.”

Falletta and the Buffalo are in the middle of a short tour of Florida cities that brings the band to the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach on Sunday night and Monday afternoon. French pianist Philippe Bianconi is the guest soloist Sunday night for the Rachmaninov Third Concerto (in D minor, Op. 30) on a program that also includes the Beethoven Fifth Symphony (in C minor, Op. 67).

On Monday afternoon, the Puerto Rico-born clarinetist Ricardo Morales, the principal clarinet of the Philadelphia Orchestra, plays the Mozart Clarinet Concerto; Falletta also will conduct Jacques Ibert’s Hommage à Mozart and the Sixth Symphony (in D, Op. 60) of Antonin Dvořák.

Falletta, 59, a native of Queens who studied at the Mannes College of Music and the Juilliard School, has been leader of the Buffalo Philharmonic since 1999. In addition to her duties in Buffalo, she is wrapping up a three-year term at the helm of the Ulster Orchestra, leads the Virginia Symphony in Norfolk, and is principal guest conductor of the Phoenix Symphony and the Brevard Music Center summer institute in North Carolina.

She has a vast and hugely impressive list of accomplishments that include two Grammy Awards for her disc with the Buffalo in 2009 of John Corigliano’s Mr. Tambourine Man, a song cycle based on lyrics by Bob Dylan. She has made more than 75 recordings with more than a dozen orchestras, often leading rarely heard repertoire (Suk, Dohnanyi, Griffes) and contemporary American music by composers such as Adolphus Hailstork and Kenneth Fuchs.

Falletta also has been featured as a classical guitar soloist on three discs, and says practicing when she can on her instrument “centers me and grounds me.” Ten years ago, in collaboration with the Buffalo Philharmonic and WNED radio, she founded the JoAnnFalletta International Classical Guitar Competition.

“The level of guitar playing from all over the world has been astonishing,” she said. There has not yet been an American winner of the biennial contest (another edition is scheduled for June 1-7), but Falletta said the mixing of guitarists from varied musical backgrounds and countries “brings everyone together” and additionally, has focused much-needed attention on guitar playing with orchestra, since the three finalists of the contest perform with the Buffalo orchestra as part of the event.

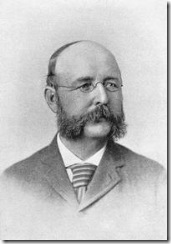

In Belfast, she is the first woman leader of the orchestra, which achieved international recognition under Vernon Handley, and when her tenure ends later this year, she will have a sheaf of highly regarded Naxos recordings with that orchestra to her credit, including music by Ernest John Moeran, Gustav Holst and John Field, along with two discs of music by Paine (1839-1906), once a major figure in American music and Harvard academia whose work is almost never heard these days, particularly by citizens of his own country.

In Belfast, she is the first woman leader of the orchestra, which achieved international recognition under Vernon Handley, and when her tenure ends later this year, she will have a sheaf of highly regarded Naxos recordings with that orchestra to her credit, including music by Ernest John Moeran, Gustav Holst and John Field, along with two discs of music by Paine (1839-1906), once a major figure in American music and Harvard academia whose work is almost never heard these days, particularly by citizens of his own country.

“This is a forgotten piece of American musical history, which is tragic. We’re always playing Copland and Gershwin and later composers, but there is a whole generation before that that seems to have become lost in obscurity,” Falletta said. The Paine discs include his two symphonies and the Shakespeare-inspired tone poems As You Like It and The Tempest. “Naxos was interested in John Knowles Paine and wanted to try this repertoire with the Ulster Orchestra … These pieces are really worthy of our attention.”

Falletta’s interest in off-the-canonical-path repertory was buttressed in her years with the now-defunct Women’s Philharmonic of San Francisco, which played only music by women. “When they called me up about the job, I realized I did not know one piece by a woman composer” save for Romantic French composer Cécile Chaminade’s lovely Flute Concertino. “I went out there and discovered there was a lot of music I had no idea about, and composers about which I had no idea. Every concert was a discovery; it was all new to me, and it gave me an appetite for finding music that people don’t know and that is unjustly neglected.

“I have this great desire to look for these pieces, to record things other than the Beethoven and Brahms and Mozart we always play,” she said.

Playing the same pieces is often a function of concert promoters, whom Falletta says underestimate today’s audiences.

“They decide they can’t sell tickets to anything but the top 20 pieces, the greatest of all time, and I think it creates fatigue. They want to hear something they haven’t heard before – they might say, ‘We heard that last time, let’s wait until there’s something new,’” she said.

“They don’t only want to hear ‘The Four Seasons.’ Audiences are very intelligent, and while they may not have any musical training, that’s not a requirement,” Falletta added. “They’re very curious and intelligent and they want to be introduced to things, and we don’t give them enough of a chance.”

It’s no small irony, then, that the Beethoven Fifth is on the Kravis program Sunday night. Finding something new to say about this thrice-familiar work was a challenge.

“We went back to the score and tried to see exactly what Beethoven wrote. We didn’t want to be too influenced by old LPs and performances,” she said. Fortunately, the greatness of the piece offered its own rewards.

“It’s an amazing piece; the first movement starts with four notes, three G’s and an E-flat, and that’s the whole movement,” she said. “That motif is in there somewhere everywhere. And I was amazed: Who could have thought of doing that at that time? Who would have dreamed it?”

Less familiar, but still a part of the standard repertory, is the Dvořák Sixth, a sunny, beautiful work redolent of the composer’s most generous style.

“It’s the most warmhearted piece. He is pouring out his love for his people. It’s so Bohemian, it’s so big. The music is what he must have been like: A very warm, kind of earthy man, a man of the people, of his town and his country,” Falletta said. “Dvořák, more than any other composer … is completely unpretentious, and all of that shines through. That doesn’t mean it’s simple at all, it’s actually meticulously crafted.”

But the music has “a glowing warmth and sincerity” that obscures the canniness of its construction, a skill that was well-earned by the composer, who played the viola for years in opera orchestras and the like in his Czech homeland.

Of the two concerti, the Rachmaninov is one of the most popular, and also perhaps the most difficult, not just for its virtuosic writing but also for its length and the sheer stamina it requires, Falletta said.

“To get to the end with strength to spare requires enormous endurance … Rachmaninov was one of the greatest virtuosos of all time,” she said, but the thing that makes the concerto extra special is the richness and depth of its orchestration. “Chopin and Paganini in their concertos weren’t too concerned about the orchestra. But not Rachmaninov. This is a symphony … the orchestra works with the pianist to make these incredibly rich textures.”

And Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto (in A, K. 622), written near the end of his life for a clarinetist friend, remains the gold standard for all clarinet concerti. “Clarinetists have Mozart’s friendship with Anton Stadler to thank. He was interested in people, and when he met this virtuoso of the basset clarinet, that opened the door to a sublime concerto,” she said. “And it’s also really heavenly to conduct.”

Now in her 15th year with the Buffalo, Falletta said while tough economic times have been hard on arts organizations, the BPO has “an incredible relationship with our administration,” she said, singling out executive director Daniel Hart in particular for his leadership. “We’re all working for the same thing … but it isn’t easy in a fragile economy. But the music is so important, and so strong, and it’s our job to take care of it.”

Meanwhile, female conductors continue to make strides in a field still dominated by males. In 2012, she led the Ulster Orchestra at the prestigious Proms series in London, and last year, Alsop became the first woman to lead a Last Night of the Proms concert.

Falletta has been a mentor to other women conductors and says she sees increasing numbers of them in good apprenticeship programs and at the heads of smaller orchestras.

“The music world has changed,” she said. “It has not changed as much as I thought it would have changed, but I think audiences are very accepting of us now.”

JoAnn Falletta and the Buffalo Philharmonic play concerts Sunday night and Monday afternoon at the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach with pianist Philippe Bianconi (Sunday) and clarinetist Ricardo Morales (Monday). The concerts are set for 8 p.m. Sunday and 2 p.m. Monday. Tickets are $25 and up. Call 561-832-7469 or visit www.kravis.org.