You can forgive Gerard Schwarz some special fatherly pride when he talks about his youngest son, Julian.

They are, after all, in the same business.

“He’s got tremendous gifts, and he’s had quite a bit of success already,” said Schwarz, an eminent American conductor who led the Seattle Symphony to major-league status over a 26-year directorship before stepping down in 2011. His son, a 21-year-old student at Juilliard, his father’s alma mater and where he is the eighth member of the family to attend the school, is a rapidly rising cellist.

“He’s just a great, great kid, and I’m very proud of him, and of course, I love making music with him. It’s the most fun for a father and son. What could be more fun?” he said.

The two have worked together in concertos by Dvorak and the American composer Sam Jones, as well as in the Konzertstuck of Ernst von Dohnanyi (here they are on YouTube), but Schwarz said he’s careful not to push his son on concert promoters.

“It has to go two ways. I don’t ever impose him on someone, but if someone says to me ― ‘We’re looking for a young soloist who’s not going to cost too much. Do you have any ideas?’ ― well, I’m all over that,” he said, laughing.

On Sunday afternoon, Schwarz père et fils will collaborate with the Boca Raton Symphonia in a performance of the Cello Concerto No. 1 (in E-flat, Op. 107) of Dmitri Shostakovich, on the second concert of the Symphonia’s current season. The elder Schwarz also will lead the orchestra in the Orchestral Suite No. 3 (in D, BWV 1068) of J.S. Bach, the second of Schubert’s two Overtures in the Italian Style (in C, D. 591), and the Miracle Symphony (No. 96 in D) of Haydn.

All of Schwarz’s four children – the others are a physician, artist and producer at CNN – studied music at home, but it was Julian who started to see it as a career during his time at a music camp when he was 11.

All of Schwarz’s four children – the others are a physician, artist and producer at CNN – studied music at home, but it was Julian who started to see it as a career during his time at a music camp when he was 11.

“He liked the idea of saying he wanted to be a musician, but he wasn’t putting in the time,” Schwarz said, so he and his wife Jody sent Julian to camp. “There was nothing to do there but practice, so we thought, ‘He’ll either start practicing and then he’ll have the potential of being a musician, or he’ll quit, and he’ll just do it as a hobby.’”

And he came back as a practicer, Schwarz said. “And we were thrilled, because as you know, it’s 10 or 20 percent talent, and 80 or 90 percent hard work,” he said.

Schwarz, 65, began his career as a trumpet player, joining the New York Philharmonic as its co-principal trumpet in 1972, a job he held for five years. He switched thereafter to conducting, and in addition to his work in Seattle, led the Mostly Mozart Festival in New York, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, the New York Chamber Symphony and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic.

He is currently director of the Eastern Music Festival in Greensboro, N.C., and well as the All-Star Orchestra, a group of musicians from top American symphonic ensembles who work with him on a public television series to increase awareness and appreciation of classical music. Episodes in Season One included Politics and Art (featuring the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony and Robert Beaser’s Ground Zero) and Mahler: Love, Sorrow and Transcendence, featuring the Songs of a Wayfarer, the first movement of the Second Symphony, and Of Paradise and Light, a piece by Augusta Read Thomas.

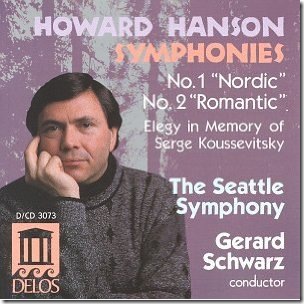

It’s no accident that all the programs on the show include contemporary American music. Schwarz’s building of the Seattle Symphony went hand-in-glove with his advocacy of American composers, and his recordings for the Delos label beginning in the late 1980s reintroduced his countrymen to the work of David Diamond, Walter Piston, Howard Hanson and William Schuman, among others.

“When I was doing the music, I did it because I loved it. I’d loved it since I was a little kid,” said Schwarz, a native of Weehawken, N.J. “I studied with [composer Paul] Creston in high school; I went to Interlochen, and the Interlochen theme was from the Second Symphony of Hanson. I was a trumpet player, and of course very interested in trumpet music, which was Torelli or Telemann and everything American, whether it be [Aaron Copland’s] ‘Quiet City’ or the Capricorn Concerto of Sam Barber.

“So I got to know all those pieces, not ever thinking, ‘This is American, and it’s not played very much.’ I mean, you never even think about that,” said Schwarz, who also studied with Roger Sessions and knew Copland, Barber and many of the other eminent composers of that generation. “I just thought a lot of the music, and I just started programming it without trying to change the world or affect anything.”

It was his engagement with the Delos record label that allowed him to “see the potential of what I could do and of the greatness of this music,” he said. Delos founder Amelia Haygood and label vice president Carol Rosenberger heard Schwarz conduct a Hanson symphony and approached him about recording it, he said.

“I said, ‘I’d love to, nothing would make me happier. But you have to understand: the critics don’t like this kind of music,’” he said, adding that learned opinion in the late 1980s was hostile to the heart-on-sleeve Romanticism of composers such as Hanson. But Haygood said she’d commit to recording the music of the mid-century American symphonists, and Schwarz went ahead.

“That was it; that was the beginning. And it became a hit. It became an economic hit, it became a critical hit, and then the floodgates opened, and I was allowed to do all my favorites,” said Schwarz, whose total discorgraphy numbers about 350 recordings. He has been nominated 13 times for a Grammy award, has two Emmys and six ASCAP awards. “And there’s so much more I haven’t done from that same period … I didn’t record all the Diamond, I didn’t record all the Piston, I did very little of Roy Harris. But I did record all the William Schuman, and that’s one of my favorite accomplishments.”

Speaking from his home in New York, Schwarz said he was working that day on some figured-bass realizations for a future performance, a busy-work task that allows him to have background music on while he does it.

“I put on the William Schuman Eighth Symphony … isn’t that a bizarre thing to choose? I just love this music; it’s a little more severe than most, but it has a language that touches me. And I guess that’s the key. It’s not going to touch everybody, but it touches me.

“Now, the tragedy is, take a look at the programs of the New York Philharmonic, or Boston, or Cleveland, and see how many pieces of Howard Hanson or David Diamond or Walter Piston or Bill Schuman or Paul Creston are there … you just won’t get it. It did for a while; when I did that, everybody started playing it, and you could see a real upturn of pieces being played. And now it’s receded again. Why is that? I don’t know.”

There is still critical resistance to this native music, he said, and tells the story of a conversation he had with the late American composer Stephen Albert, who was composer in residence at the Seattle Symphony from 1985 to 1988. Albert had heard from fellow composer Libby Larsen that Seattle was doing more American music than any other orchestra in the country at the time.

“He asked me, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ And I said, ‘I’m not going to do anything about it.’ And he said, ‘Shouldn’t we just tell everybody and make a big splash about this?’ And I said, ‘No, in fact I don’t want you to tell anybody. Don’t you dare tell anybody.’”

To Albert’s expression of disbelief, Schwarz explained his position:

“’Stephen, we’re having a big success. Audiences are growing like crazy. They like the music. Nobody’s complaining, and we’re doing a lot of American music. It’s great. If I tell them how much American music I’m doing, they’re going to start complaining,’” he said.

Schwarz’s tenure in Seattle also included the sometimes controversial building of Benaroya Hall, which sits cozily in the heart of a downtown street. He believes strongly in the importance of a vital urban environment, and also in the crucial role that cultural institutions play in economic development.

“The cities that have embraced the idea of an important symphony orchestra being a part of the fabric of their lives, especially in a downtown setting, have profited tremendously by it. A place like Seattle, even people who were not necessarily classical music fans understood the importance of having a great symphony orchestra in the fabric of its life. And we understood that we have to make sure that the community sees us as their orchestra,” he said, adding that he had formed a community orchestra in Seattle whose function was to simply read through repertoire a few times a year.

Schwarz said the Seattle Symphony made a concerted effort to do that, so that by the time a new concert hall was in the offing, it had the support of the city’s mayor and the city council.

“[An orchestra] is a phenomenal thing for a community, and quite frankly, it’s a lot cheaper than an opera company or a ballet company,” he said.

Although Sunday’s program does not feature any American music, it does have a 20th-century work in the Shostakovich concerto, which was written for Mstislav Rostropovich in 1959 and since then has quickly established itself as a standard work. Shostakovich himself, who died in 1975, is one of the only composers of the past 50 years to have become a steady part of the repertory, and Schwarz said there are good reasons for that.

“Does it matter that it’s all very traditional? Does it matter that harmonically, it’s not unusual? That melodically and rhythmically it’s very much in the Russian school of Rimsky-Korsakov? It doesn’t matter,” he said. “The key is that the music’s wonderful. The tunes are great, the emotional impact is great. He allows music to unfold in a very unique way…

“He was amazing, and the audience – and I’m a great believer in the audience – they got it. They said, ‘Wow, this is great stuff.’ And then everybody played it. We all played it,” he said. “In the end, the audience is the arbiter. Maybe not the first performance, but over time, they’re the arbiter. If you’re going to do the Shostakovich Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, if you’re going to do those symphonies, will people come? Do they care?

“The answer is ‘Yes,’” he said.

The Boca Raton Symphonia performs at 4 p.m. Sunday in the Roberts Theater on the campus of St. Andrew’s School in western Boca Raton. Tickets: $33-$59. Call 866-687-4201 or visit www.bocasymphonia.org.