For a band that lasted less than three years between 1966 and 1968, Cream cast a long shadow, influencing the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Jeff Beck Group, Led Zeppelin, ZZ Top, and countless others. But considering the trio’s all-star personnel of guitarist/vocalist Eric Clapton, vocalist/bassist Jack Bruce (1943-2014) and drummer/vocalist Ginger Baker (1939-2019), that isn’t surprising.

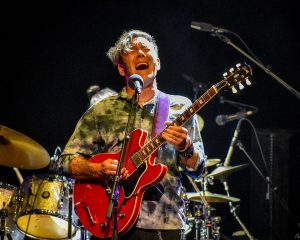

And considering how tribute acts have capitalized on the interests of baby boomers in the music of their youth during the 21st century, it wasn’t surprising that Baker’s son, drummer/vocalist Kofi Baker, and Clapton’s nephew, vocalist/guitarist Will Johns, brought The Music of Cream to Wells Hall at the Parker Playhouse in Fort Lauderdale on April 7.

Rounded out by bassist/vocalist Kris Lohn and keyboardist/guitarist/vocalist Stephen Ball, The Music of Cream’s Disraeli Gears Tour featured Cream’s 1967 sophomore studio release in its entirety, and more, during the first set. The venue filled only to roughly half-capacity, in contrast to Baker’s report of pre-COVID 19 sellouts.

Perhaps the sparse, aging crowd — hardly anyone was wearing masks — proved that the boomers are still often proceeding with caution, or that the five-year-old group’s previous lineup with Bruce’s son, bassist/vocalist Malcolm Bruce, was more of a draw as a true legacy act.

The classic “Strange Brew” provided the band with a good warmup vehicle, as Johns’ lead vocals were augmented by the harmonies of Lohn and Ball, who added rhythm guitar, as he would for most of the opening set. Another radio-friendly gem, “Sunshine of Your Love,” was even better. The original co-lead vocals of Clapton and Bruce were mimicked by Johns and Ball, who actually provided more Clapton-like vocal tones throughout the evening (and Johns more Bruce-like inflections).

Baker’s rearrangement of his father’s Native American drum figure, the suggestion of recording engineer Tom Dowd after traditional drum parts originally failed to propel the piece, included accents on the up beats. And the track’s extended, unpredictable ending — a staple of Cream, a band that loved to improvise in live settings — provided authenticity.

The sequential “World of Pain” was another highlight in which Johns traded lead vocals with Lohn, whose stage-prowling energy proved infectious all night. Their harmonies with Ball accurately captured the sound of the original recording, and Johns’ stinging solos echoed his uncle’s. “Dance the Night Away” was then most notable for its three-part harmonies and the psychedelia element that Cream helped to make an inimitable part of the mid-to-late-1960s rock era.

“This next song was written by my dad,” Baker said afterward. “It’s called ‘Blue Condition,’ and I’m going to try to sing it for you.”

Baker’s vocal attempt on the waltzing tune wasn’t his personal highlight of the show, but his father likewise excelled more at spoken word, as did Baker later on the deep Cream cut “Pressed Rat and Warthog.” The drummer also sidestepped the elder Baker’s inimitable, often tribal drumming style, favoring the influence of progressive rock and jazz/fusion veterans like Terry Bozzio (drummer for Frank Zappa, Jeff Beck, and U.K.). With his hair tied back, Baker even resembled one of Bozzio’s multiple looks during his lengthy career.

“I love doing my dad’s music,” Baker added afterward, “because it’s so great. Don’t you think we should keep it going?”

The audience approved, as it did for the Disraeli Gears side two LP opener “Tales of Brave Ulysses.” Ball’s lead vocal, and Johns’ Clapton-like use of his wah-wah pedal, made for another highlight, though the best part of the subsequent gem “SWLABR” would be its comic lead-in by the two Cream relatives.

“What does it mean?” Johns asked of the jumbled title.

“Drugs,” Baker deadpanned, before Johns went on to explain that Bruce’s lyrics actually told the tale of a man, scorned by a female celebrity, who tried to get even by drawing beards and mustaches on her likenesses around town. But aside from being performed too fast, the track also suffered from some misplaced notes by the otherwise dependable Lohn as he navigated the Cream bassist’s often complicated lines.

A dramatic “We’re Going Wrong” righted the ship. Baker played his drums with mallets; Lohn redeemed himself with a formidable bass solo, and Ball sang lead and played guitar before switching to keyboards for Cream’s cover of Arthur Reynolds’ “Outside Woman Blues.” Johns’ lead vocals, and evocative soloing on the lone Disraeli Gears cover tune, proved Cream-legit.

“Take It Back” featured a lead vocal by Lohn and harmonica by Ball, the Swiss Army knife of The Music of Cream, who took to the keyboards for the traditional album closer “Mother’s Lament.” Its sans-instruments singing by Johns, Lohn and Baker, out from behind his drum kit and also up front, turned the vehicle into a British drinking song.

The hour-long first set closed with the aforementioned “Pressed Rat and Warthog” and another epic from Cream’s 1968 studio double-LP Wheels of Fire, “White Room.” Ball played keyboards; Johns and Lohn traded Bruce and Clapton’s lead vocal phrases, and the guitarist dramatically soloed into accents and a downshifted section near the end that truly echoed the band the quartet was paying tribute to.

Set two, featuring Clapton material from his solo career and with other all-star acts like Blind Faith and Derek and the Dominos, failed to provide such drama. Because as much as Cream harnessed their collective improvisational stage performances in the studio, simplifying parts to successfully gain radio airplay, it was Clapton who wanted to further simplify things post-Cream in the name of commerciality.

He succeeded in the decades afterward, of course. But by comparison, The Music of Cream’s recreations in set two, with Ball mostly playing keyboards, lacked the same energy. Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff” neared lounge-ish smooth jazz, and even staples by Blind Faith (“Can’t Find My Way Home,” with Ball adding acoustic guitar to his lengthy tool belt) and Derek and the Dominos (“Layla,” with a hearty effort by Johns and Ball to equal the mountainous lead guitar roles of Clapton and Duane Allman), came up slightly short.

Fittingly, the set two highlight was Cream’s “Badge,” a tune written by Clapton and George Harrison that was featured on the trio’s self-descriptive 1969 studio coda Goodbye. Its interplay, extended arrangement through a fake ending, and atmospherics again begged the question of what else Cream could’ve accomplished had it not decided to so prematurely say farewell.