By Robert Croan

South Florida Symphony’s Summer with the Symphony series — one monthly chamber music concert in Miami and in Fort Lauderdale — is the oasis in South Florida’s off-season classical music desert.

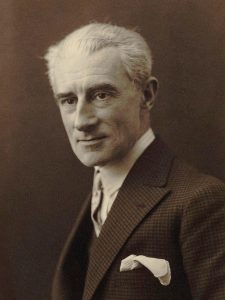

Responding to this cultural void, an enthusiastic capacity audience filled the attractive auditorium of Fort Lauderdale’s Center for Spiritual development for the final concert July 26. The pairing of string quartets by Felix Mendelssohn and Maurice Ravel (though all too brief — barely an hour of music, not counting the spoken commentaries) was well worth the visit.

Violinists Huifang Chen and Mei Mei Luo, violist Brandon Wu and cellist Claudio Jaffé, first-desk players in the orchestra, although they only perform publicly as a quartet on rare occasions, displayed a give and take and singularity of purpose much as if they were accustomed to working together as a team — which they do, of course, in the orchestra, although not in quite the same way.

The prodigy Mendelssohn composed his String Quartet No. 2 (in A minor, Op. 13) at the age of 18, in 1827, the year Ludwig van Beethoven died, and this work was an homage to the older composer. At the start, Mendelssohn uses a phrase, “Ist es wahr?” (Is it true?) from one of his own songs — analogous to a quote Beethoven used in his String Quartet No. 16 (Op. 135): “Muss es sein?” (Must it be?). That fragment opens the work and later reappears in the finale, in both cases presented by the first violin as an introduction or addendum to the main body of the movement in the form of a seemingly vocal recitative. The rest of the opening movement is a traditional Allegro vivace in sonata allegro form, which the South Florida players rendered with spirit and a sense of fun.

The slow movement that flows features a more erudite fugal section, in which clarity of the competing “voices” was admirably achieved. Most engaging was the Intermezzo — actually a jocular scherzo of the kind that would become a specialty of this composer. Think of it in terms of his more familiar incidental music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The players seemed to revel in the technical challenges here, as well as in the gravitas and other expressive demands of the final movement’s shifting moods.

And what a perfect way to complete the season: with one of chamber music’s towering masterworks: Ravel’s melodious and colorful Quartet in F Major. Classically architectonic, nonetheless impressionistically ephemeral, cool and breezy and playful, it was ideally suited to the warm and humid summer evening.

The players took the opening sonata form movement a little slower than the norm, perhaps to draw out the music’s evocative textures and set into relief the contrasting thematic motifs. They made up for it in their playful delivery of the scherzo, with its pungent pizzicatos and unexpected rhythmic intricacies. The slower third movement reveled in splashes of sonic hues, suggesting what it might be like to listen to a Renoir painting. The finale whirred to a conclusion that summed up the event’s entire experience. The twizzle of alternating rhythms effectively articulated how much these admirable artists had enjoyed the very act of making music together.

In view of this year’s enthusiastic audience response, might it be possible to hope for a longer series next year, or even some chamber music — sorely lacking in this area — during the regular symphony season?