It was the love of Central American art that brought co-authors Suzanne Brooks Snider and Mark Morgan Ford, of Ford Fine Art, together more than a decade ago.

A labor of love and passion project for the two, Snider and Ford spent eight years writing and researching their new book, Central American Modernism/Modernismo en Centroamérica.

A large, coffee table-sized 7-lb. tome, consisting of more than 300 pages in English and Spanish and organized by country, the book focuses on the art of that region, which they say has been overlooked by the international art world.

“We hope this book brings attention to the art and artists in this part of the world, which have been historically discounted and under-represented,” Snider says. “The time has come to give Central American modernist art and the artists who created these works the respect they deserve. And we hope that writing this book will give them the exposure that is long overdue.”

Noting that there were very few and reliable books on the art of individual Central American countries and none covering the region as a whole, the two set out to write the history of modernist art in Central America. An exhibit at the Cornell Museum of Art in Delray Beach, now running through Aug. 25, displays works by several of these modernist artists.

“The significance of Central American artists, their recent entry into the art market and recognition among collectors and institutions will be greatly enhanced by the information included in this publication,” says art historian Carol Damian in the foreword to the book.

“The book elevates artistic and creative production in Central America above earlier notions that there was an absence of serious intent and intellectualism and an emphasis on the folkloric and regional,” she says.

Modern art of Central America has similarities to the modern art of Mexico and South America, but possesses distinctive qualities that sets it apart. Snider and Ford set out to identify important modern artists from each country and secured original documentation, interviewed historians, museum directors and gallery owners and obtained permission to photograph and reproduce many of the artworks in the book.

They discovered that most influential Central American modernists shared a common denominator. They left home to study abroad — in Europe, North America or Mexico, were exposed to new ideas and schools of art and brought those ideas with them when they returned home.

The book is part of a larger project, in which Ford and Snider are working to create a sculpture garden, Paradise Palms and Sculpture Garden, and future museum to house Central American modernist art on 40 acres of land in west Delray Beach. Twenty-five acres have been landscaped and include a bamboo forest, a Zen garden, a child’s playground, a Chinese teahouse, the Garden of Eden, a mountain rock garden and a number of sculptures.

Starting in Guatemala, the book focuses on artists Rodolfo (“Marco”) Abularach, Roberto Cabrera and Carlos Mérida, best known for transliterating European modernist painting into Latin and Central American themes and motifs.

Like many other Central American artists of his era, Mérida studied abroad in Paris where he met Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and Roberto Montenegro and well-known European avant-garde painters. He then spent time in New York and Mexico.

Returning home, he began to incorporate his indigenous heritage into the modernist techniques he had learned in Europe and for his 1915 show he married Cubism and abstraction to re-envision the sensibilities of native Maya art, a turning point which is now considered to be the advent of modernism in Guatemala.

One of these paintings is his playful Dances of the Birds (1938), from the Dances of Mexico series, depicting an ancient religious ceremony celebrating the quetzal bird, or national bird of Guatemala, and the spirit guide of the ancient Mayas. Two brightly colored geometric human-like bird figures (with triangular heads, or beaks) dance in front of two large red, white, blue and black-colored circular headdresses.

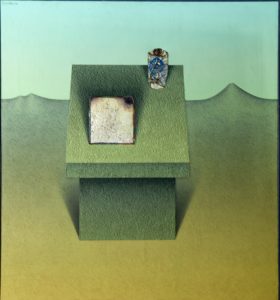

In neighboring El Salvador, the book highlights the work of Ernesto “San” Avilés, Carlos Cañas and Benjamin Cañas (no relation). Benjamin Cañas began his career as an architect before turning his focus to abstract and surreal art. After living in Guatemala, in 1969 he emigrated with his family to the U.S., where he was part of the design team for the Watergate shopping promenade in Washington, D.C., for which he won a design award.

It was during the 1970s that Cañas’s interest in mythology and ancient civilizations took hold, painting angels, satyrs, dwarfs and nymphs in a magical realist style exploring themes of creation, civilization, destruction, evolution and rebirth.

The only woman modernist in the book, El Salvadoran artist Rosa Mena Valenzuela, known as the ambassador of expressionism in her home country, counts Jackson Pollock, Paul Klee, Marc Chagall and Pablo Picasso as influences. Growing up in a musical house, Valenzuela credits that early exposure to music as a catalyst to her art, which she came to later in life.

“I think that without a musical ear, I wouldn’t have been able to achieve a feeling for color,” she said.

Her expressionist style has been described as spontaneous and she herself called it, “a new style in rapid and dizzying lines that make the figures move.”

This rapid-fire style is evident in the 1970 portrait she painted, Retrato de Valero Lecha, of her mentor and teacher, Spanish painter Valero Lecha. Known also for her abstract collages, Valenzuela incorporates scraps of fabric, paper, cardboard, industrial paint, aluminum and cement.

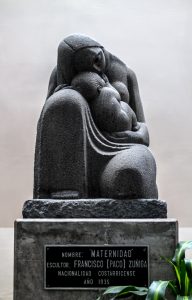

In Costa Rica, where Snider once ran a surf shop on Tamarindo Beach, she and Ford turn their lens on to Francisco (“Paco”) Amighetti, Manuel de la Cruz Gonzáles and Francisco (“Paco”) Zuñiga, considered to be Central America’s most important sculptor and one of the world’s most important modernists.

Known for his subjects of indigenous and native women, Zuñiga depicted the women in everyday activities. His 1965 watercolor and ink titled Conversación depicts two indigenous-looking women dressed in white peasant skirts sitting cross-legged and side-by-side on the street, chatting and (presumably) selling earthenware pottery.

With their love of Central American art and artists, the authors hope to elevate the profile of the contributions these artists have made.

“We are proud of this book,” Ford writes. “It is something that has not existed before. We are hopeful it will stimulate more research and bring more attention to this underrepresented body of work.”

Other artists among the 30-plus mentioned in the book include Efrain Racinos from Guatemala; Raul Elas Reyes and “Salarrué” Salvador Efrain Salazar Arrué from El Salvador; Dante Lazzaroni and Begnino Gómez from Honduras; Armando Morales and Fernando Seravia from Nicaragua; José Sancho and Manuel de la Cruz González from Costa Rica and Manuel Chong Neto and Alfredo Sinclair from Panama. For more information, visit centralamericanmodernism.com.

Central American Modernism runs through Aug. 25 at the Cornell Museum at Old School Square, 51 N. Swinton Ave., Delray Beach. There is a talk today (June 23) about the book from 1:30 to 3 p.m. at the Cornell with Snider, Ford and art historian Carol Damian.