It’s probably not well-known among average concertgoers that American composers in the 20th century created a significant body of music for string quartet.

While a movement from one of those quartets, the slow movement from Samuel Barber’s lone effort in the medium, now better known as the Adagio for Strings, is famous the world over, the rest of that quartet, as well as dozens of other worthy American quartets, almost never get a hearing.

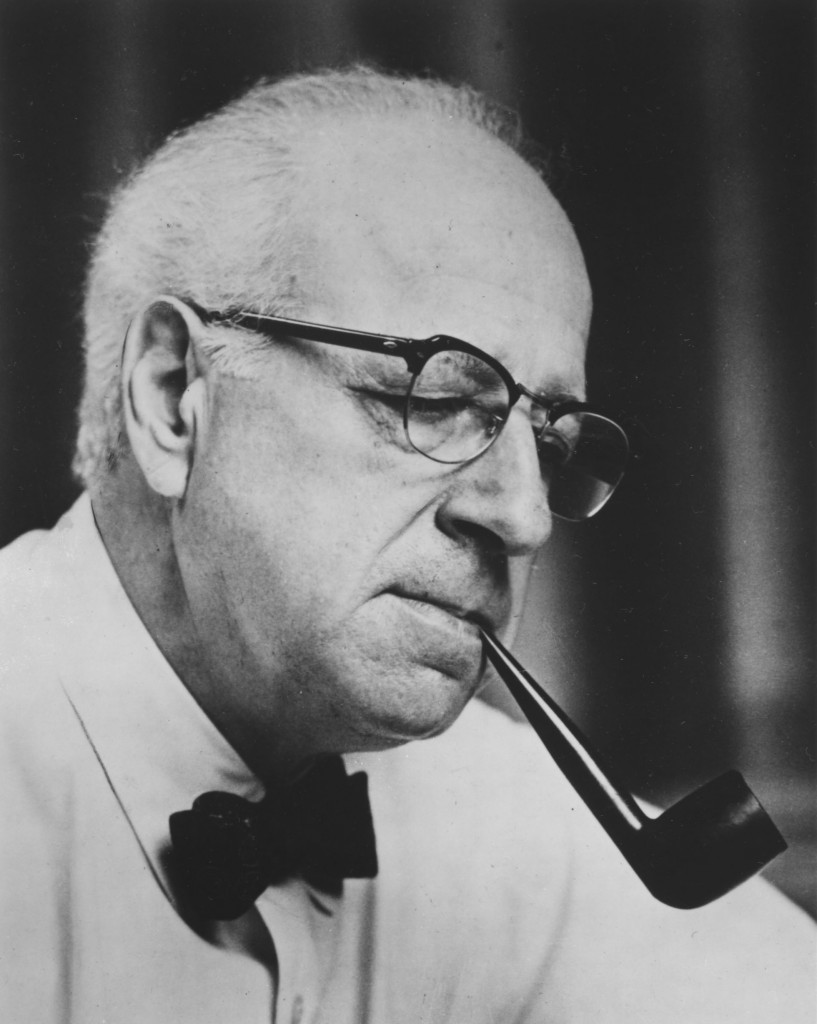

For its first program of the season, the Delray String Quartet remedied that situation with a performance of the First Quartet by Walter Piston, which was included on a program with music by Beethoven and Dvořák. Piston is a major figure in American music of the last century, with a fine legacy of books on theory and a stellar list of students he taught at Harvard University to add to his large catalog of works.

But Piston doesn’t get many outings these days, though not long ago his ballet score The Incredible Flutist was relatively well-known. It seems to have vanished from the concert stages, but the First Quartet is a fine and exciting piece that got enthusiastic approval from a small house at the Colony Hotel in Delray Beach on Oct. 30.

Written in the early 1930s, the quartet speaks a language of neoclassicism and highly sublimated jazz. It’s exciting and subtle at the same time, spotlessly crafted, and urgently communicative. The outer movements are busy and joyous, with a bluesy motif that is the climax of a big buildup in the first, and in the short finale, the rhythms are swingy and dance-inspired amid a buzzing, moto perpetuo texture.

The second movement is the weightiest, with a mournful, wee-hours solo from the cello (played beautifully here by Claudio Jaffe) set off by lonesome, high-register chords in the other strings. The mood darkens into an intense contrapuntal outburst before the quiet of the opening pages returns; it’s a lovely piece of writing and sounds distinctly American.

The Delray (which plans to play a quartet by another overlooked American, Quincy Porter, next season) made a strong case for the Piston, with an abundance of energy in the outer movements and plenty of sensitivity in the second. The Delray quartet has done some yeoman work with new American music by commissioning quartets by Kenneth Fuchs and Richard Danielpour; the Piston and Porter to come can help it further establish a good niche for itself as a quartet that champions American music.

The concert opened with another rarity, Beethoven’s own arrangement (Hess 34) of his Piano Sonata No. 9 (in E, Op. 14, No. 1), which he transposed up to F major for the string quartet version. This is early music, dating from 1798, and it works very well for string quartet. It inhabits the same sound world as the Op. 18 quartets that inaugurated the composer’s great series of works in this form.

The Classical repertoire tends to be second choice for the Delray, but this work’s straightforwardness and modesty seemed to fit the foursome well. The little scampering sixteenth notes after the opening motif in the first movement came across as rushed and none too clean each time they appeared, but overall the sonata got a graceful, elegant performance.

The final work on the program was the Quartet No. 10 (in E-flat, Op. 51) of Antonin Dvořák. This is a sure crowd-pleaser, full of memorable tunes and narrative excitement, and completely idiomatic string writing by a man who was a professional violist. This is the kind of repertoire where this quartet sounds most comfortable, and they demonstrated that, turning in a reading that was somewhat better than their version of this composer’s more famous American Quartet (No. 12 in F).

The first movement was rich and warm, with good ensemble and sound blend, and in the dumka second movement, the other two strings laid well back for the opening to allow the first violin and viola to trade their motifs back and forth (there was some disagreement about whether to make the end of the theme straight or grace notes). The faster tempos in the movement were well-paced, and the slower dumka music had pulse and forward motion.

The quartet also made sure the Romanze tempo wasn’t too slow, critically important in such a mellow quartet once you get to the third movement. The musicians played it with intensity, though there could have been some more dynamic contrast to bring the deep emotion of this movement a little more. The finale had a good, snappy feel even if it was a little on the sluggish side; here again, more contrast, in the form of a lighter approach, could have made the movement stand out some more.

But it was a very good reading overall, and the audience adored it. Still, the Piston Quartet was the day’s most important moment, and to hear the Delray programming this fine piece of American music was cheering indeed.