By Dennis D. Rooney

Delray Beach’s landmarked Colony Hotel has been home to the Delray String Quartet for

all of its 13 years of existence.

The group’s concerts take place in a meeting room on the hotel’s main floor. It’s an attractive space but acoustically rather small to encompass this foursome’s vibrant sound, which at several points became overwhelming.

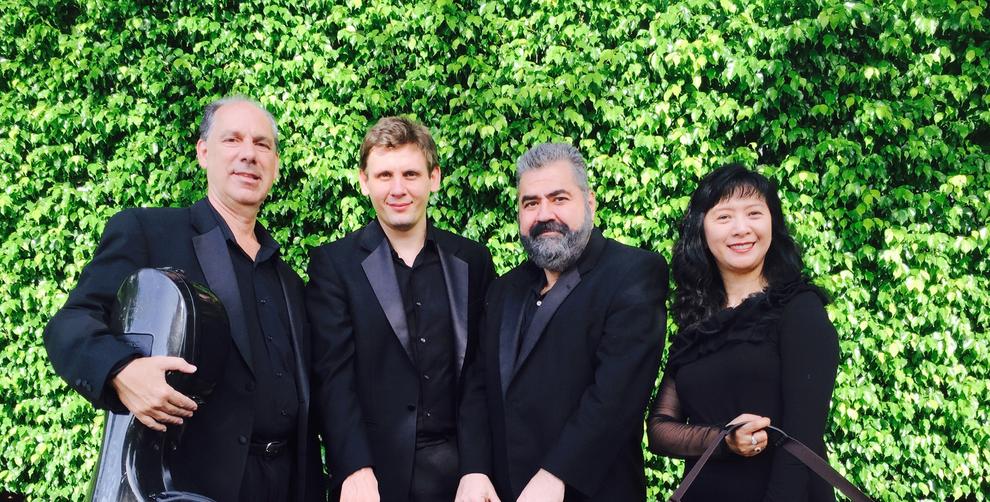

Their chosen program Sunday afternoon at the Colony offered three quintets, so violinists Mei Mei Luo and Valentin Mansurov, violist Richard Fleischman and cellist Claudio Jaffé were joined by guest violist Brenton Caldwell. The program was a study in contrast.

As an opener, the Quintet in C minor (Op. 37. No. 1) by Luigi Boccherini was tuneful and ingratiating. The players’ high technical level was immediately established, although the room acoustics emphasized that their ensemble needed some polishing in detail. The finale was the most impressive despite an occasional surfeit of emotion.

The balance of the program presented two works of Johannes Brahms. First, a transcription for quintet of the Scherzo for violin and piano the young Brahms contributed to the “FAE” Sonata he wrote jointly with Robert Schumann and Albert Dietrich. The second subject of the scherzo emerged as the most successfully transcribed.

After intermission came the same composer’s Quintet in G minor (Op. 111). Written at the behest of his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms announced to his publisher in 1890 that it would be his last published work, which as it happened would be followed by remarkable sequence of late works. Nevertheless, one can easily hear a note of valediction in this music.

Compared to the Scherzo on the first half, in the quintet Brahms has, in the words of Hans Gál, “outgrown the passionately romantic extravagance of subjectivity” and now, free from illusions, could face the world as a stoic, “without illusions and without self-pity.”

Whereas the opening Boccherini quintet was unchallengingly ingratiating, Brahms’s late work is the opposite of easy listening, rather being something of a tough nut to crack. Despite Slavonic and gypsy elements that tinge the final two movements, its dense textures, complex harmonic movement and rhythmic scheme equally challenge both performers and listeners.

Greater tonal delicacy in the opening Allegro non troppo, better articulation of the off-balance rhythmic feeling in the Un poco Allegretto, and sharper contrast between the major and minor character of the finale would have improved what was otherwise a knowing and committed account.