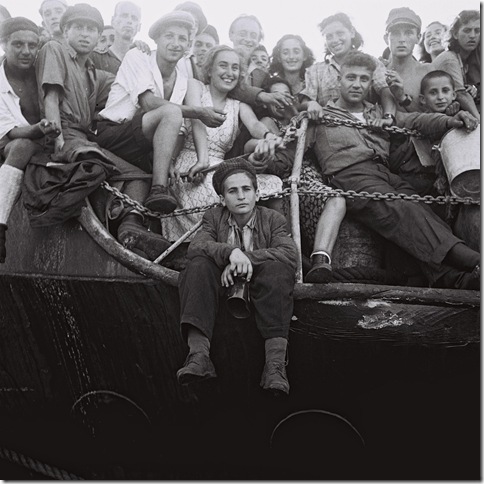

A group of Jewish immigrants enters the port of Haifa, in a photo seen in Colliding Dreams.

In late January, documentarian Oren Rudavsky brought his controversial new film, Colliding Dreams, to the area to screen it for attendees of the 26th annual Palm Beach Jewish Film Festival.

He met with Hap Erstein to talk about the film — an exploration of Zionism, the promotion of a Jewish national state, and the continuing conflicts between Israelis and Palestinians — and the audience reactions to it. Colliding Dreams returned to South Florida this past weekend, playing at several theaters across the region.

Erstein: What led you to make this film?

Rudavsky: I’ve been trying to make this movie for a long time, actually. Because it’s my family history, really. Not that any of my immediately family has moved to Israel, but my father’s father — my grandfather — was involved with the Zionists of America as a fundraiser.

So I grew up with this tradition. An early memory is the ’67 war and the great celebration that seemed to be happening everywhere among Jews, non-Jews, European countries. It was seen at David against Goliath. But after ’67, the story began to get more complicated.

As I grew up, I became drawn to Eastern Europe. I felt like I was connecting with my real roots. I made several films there, including Spark Among the Ashes, then A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, then Hiding and Seeking. After making that film in ’97, I started thinking about this film with my partner Joseph Dorman, but frankly we were both uncomfortable with a lot of what was going on in Israel. This was post-[Yitzhak] Rabin’s assassination, which seemed a terrible blow to the possibility of peace. And I frankly don’t agree with everything the current (Israeli) government does, just as I don’t agree with everything our own government in the United States does.

But I didn’t want to preach from some American perspective, so the film focuses on Israelis and Palestinians. The film’s focus is on Zionism, and therefore, Israeli Jews have more screen time than Palestinians do. Still, some people believe we give too much screen time to the Palestinian perspective.

Erstein: How early did you become aware of the Zionist movement?

Rudavsky: I was really clearly aware of it when I was in 4th grade. I was 10 years old, it was 1967. I remember going to Hebrew day school and the Israeli teacher I had was crying. We were listening to the radio, to the hourly reports of the war. The initial reports felt quite dire, before it became clear that the Israeli air force destroyed the Egyptian air force completely. That’s when I saw my teacher cry.

Modern night life in Tel Aviv, from Colliding Dreams.

Erstein: What did you learn from the interviews you conducted for this film?

Rudavsky: What I most learned was the range of opinion in Israel. That the debate here in the United States is very narrow. In Israel they yell and scream at each other, but then they go out and have coffee together, even when they violently disagree. That tends not to happen here. What happens is one side or the other basically shuts up.

In Israel, people of the extreme right who believe the state of Israel has no legitimacy, will say what they feel quite openly. And then Palestinians will speak up as well. Let me be clear, we did not speak to the ultra-extremists who want Palestinians kicked out of Israel and the West Bank. We tried to find Hamas people, who are not crazy to speak to us. Once I told them it was a film about Zionism, they would not speak to us.

Erstein: In general, was it difficult to gain the trust of interview subjects?

Rudavsky: It was a process of opening up, like a flower opening up. First you go to the people you know, then you go to people they suggest. Then you realize you’re missing a complete perspective that is important to understand.

Oren Rudavsky.

Erstein: You were trying to include a wide range of views on Zionism?

Rudavsky: What was important to me was to not make a film that spoke to the converted. I wanted to provide a range of perspectives, not just giving one narrative. I may not buy certain Palestinian narratives. I certainly don’t buy the jihad narrative or ISIS narrative. I certainly reject those narratives. But there are some Palestinian narratives, even if you agree with them, what chance is there that you’re going to sit down at a table and come to any sort of agreement?

Erstein: Do you feel you created a balanced film, covering all views?

Rudavsky: Yes, balance to me, not to everyone. We had a range of advisers who said, “Yes, you had this right” or “This is accurate.” Some people take issue with how much time we spent with, say, the intifada. Or Rabin’s assassination. But we give a great deal of time in the film to that period of history, the time of the early settlers.

The film had an earlier title, The Zionist Idea. That title came from Arthur Hertzberg, who wrote a book with that title. He was actually one of my heroes, what we would call “an open-minded thinker.”

But the word “Zionism” is, in many people’s eyes, sort of lethal. It’s a dangerous word. People told me overwhelmingly that the title of the film should not have “Zionist” in it. Because people will automatically believe that it’s pro-Zionist. I had been very invested in that title as a tribute to Arthur Hertzberg. In the end, I bowed to reality.

Colliding Dreams suggests conflict between Jews and Palestinians, but much of the conflict today is between Jews and Jews. If the Jewish people agreed with each other, I believe they could make peace with Palestinians. But they’re fighting among themselves.

Three Arab women in Israel, from Colliding Dreams.

Erstein: What reactions have you gotten to the film, say at film festival post-screening discussions?

Rudavsky: My partner Joe was just in Miami a few weeks ago and he was actually a little traumatized. The film ended and as he described it, a lady sort of rushed the stage and was very upset with him. There were four or five very powerful negative comments saying that it was not a balanced film.

Erstein: By balance, do they mean the film does not sufficiently take the Jewish side?

Rudavsky: Right. And he was a bit taken aback. And there was a woman whose child lives on the West Bank who felt we were saying they have no legitimacy to live there. The reality is that when the scores of what the film got were tabulated, the majority were positive. The vocal minority spoke much louder and the silent majority didn’t speak up.

Erstein: Who is the film aimed at?

Rudavsky: We made it mostly for the American market, but we hope there’s some Israeli market, because what Israelis told us is they don’t know their own Zionist history. And we don’t know American history, either.

Erstein: What will it take to have the film seen in Israel?

Rudavsky: We’re working on it. It’s a slow process. Slower than I would like. It’s about finding a distributor, about trying to get it on TV, it’s about getting it in festivals. It’s about Israelis who think they know their own history realizing that they don’t. And it’s also about trying to get it in the schools. That’s the end goal, educating people who don’t know the history.

This film’s a tough sell. In Florida, even if you show it in the right part of Florida, who knows if you’re going to get an audience. Nobody expects it to make millions of dollars, but I think it’s a really important film.

Colliding Dreams plays this week at the Living Room Theaters on the campus of Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. Call 549-2600 for showtimes and prices.