What 8-year construction project involved only American laborers and linked two oceans through the narrow spine of Central America at a cost of $200 million?

The answer is: none. Sorry. Trick question. If you were thinking the Panama Canal, you were half right. This costly engineering masterpiece took twice that amount of money and 10 years to complete. It required more than 70,000 workers from around the world facing torrential rains, malaria, harsh heat and dangerous mudslides.

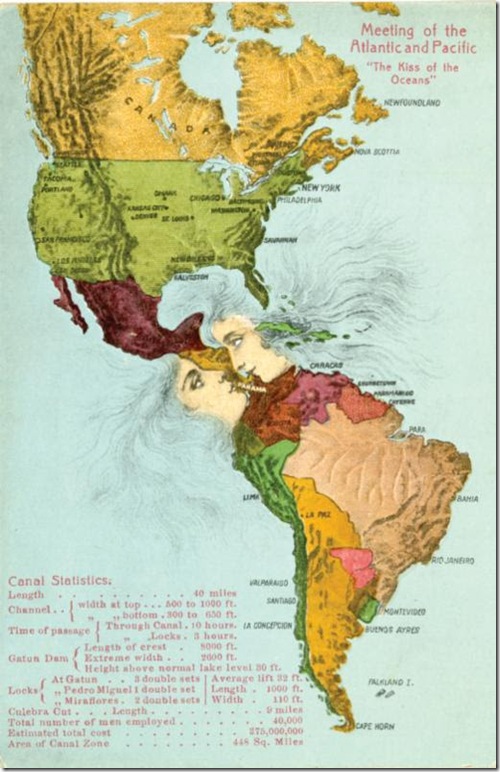

The story of the Panama Canal, its workers and its key players is being revisited now with an exhibition running through Jan. 4 at the Flagler Museum. Kiss of the Oceans: The Meeting of the Atlantic and the Pacific celebrates the 100th anniversary of a goal once thought unreachable: its completion. It consists mainly of photographs and documents and includes some artifacts.

To set up the mood and perhaps soften the harsh reality of the story, the museum walls have been painted pale pink. This makes for a romantic visit and matches the theme of a blown-up postcard in the first gallery room. The image depicts the two oceans as lovers, their lips kissing.

The exhibition takes us from the seed of the idea (as early as 1517) to the astonishing end product of August 1914. Along the way we learn of the failed attempt by the French (a catastrophe, really) and the successful American takeover beginning in 1904. The associations with Henry Flagler here are somewhat weak.

Flagler wanted to extend the Florida East Coast Railway to Key West since 1891, but waited until the Canal plan was announced to go public with the news of the extension. And while few projects can compete with the Panama Canal in size and significance, Flagler’s Over-Sea Railroad can.

The museum does its usual nice job of balancing historical facts with the human aspect. It does not let us forget that incredible structures need brains and hands to create them.

A lot of wall space explores the Caribbean and European workers, how they lived, what they ate and what they did for fun. A set of photographs from 1911 depicts a group of Italian workers and a group of Spanish laborers with their black mustaches and suspenders. They are credited to National Geographic. The magazine ran articles during the construction phase to give readers an idea of the enormity of the project. At one point, the turnover rate of skilled American laborers reached 75%. Incentives were created and clubhouses were built to keep workers socially and actively engaged. Photographs capture a bowling alley and baseball teams among other recreational activities. There are also rare, intimate images of family life.

Employees were assigned a category — gold or silver — depending on their skills. Skilled workers were paid in gold while unskilled workers received silver. This category also dictated their living quarters, water fountains and restrooms. The exhibition makes no reference to the racial discrimination in the Canal Zone described in Matthew Parker’s book Panama Fever. In fact, there was no mixing between the races except while at work and at one point only Americans were given gold status, which meant the blacks on the “gold roll” had to be removed even if they were skilled and valuable.

It is hard to tell whether laborers really knew the huge significance of the project. The romanticized notion offered by Kiss of the Oceans is that these men joined the workforce to be part of history. But it is also true that this was a chance to earn money, benefits and experience.

“$75 per month” reads an offer letter from May 1904. “You will be granted six weeks leave of absence on full pay during each year of service.”

It adds: “In case of bad conduct resulting in dismissal…no return expenses to the United States will be allowed.”

The third gallery room highlights the rewards of such a long painful endeavor. For instance, when the canal was finished, it reduced the length of the New York-San Francisco voyage to less than half of its previous 13,000-mile distance.

Don’t you see? The benefits were worth all the struggles. The exhibit seems to say.

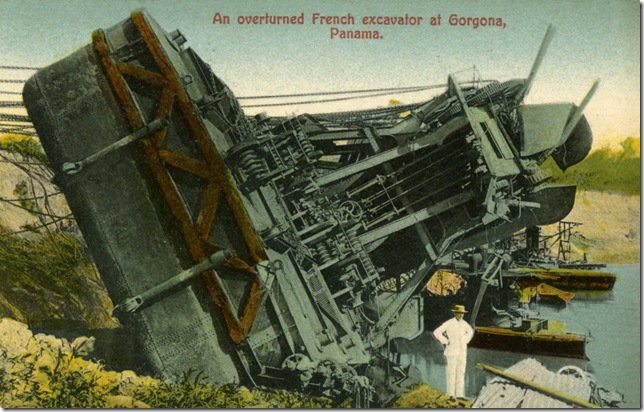

But every time we want to say yes we are reminded of yet another setback or tragedy. The 20,000 French lives lost was only the beginning. The American effort saw more than 5,000 deaths. Then there are the photographs of accidents and mudslides at the Culebra Cut, the most challenging part of the project, rising more than 360 feet above sea level, and other images depicting the fight against yellow fever and malarial mosquitoes.

An illustration by Udo Joseph Keppler depicts Death patiently waiting the arrival of more bodies to take. A landscape can be seen through her bony figure as well as the letters P A N A M A floating over the canal waters. It is titled Waiting.

As we get ready to say no, it wasn’t worth it we are hit with its commercial value and engineering significance.

A blown-up image from 1914 titled Hercules Crane depicts the massive revolving crane that serviced the canal between 1915 and 2009. It ranged in capacity from 280 tons at a 22 foot reach to 112 tons at an 82-foot reach. American steam-shovel buckets held five cubic yards of material while French dirt cars could only hold one cubic yard.

Americans simply had superior machineries and the support of a very encouraging president quoted with saying “make the dirt fly.” In fact, President Theodore Roosevelt’s visit to the Panama Canal in 1906 made him the first president to leave the United States while in office.

It is hard to decide whether the end justified the means. The one thing certain is that to complete an unimaginable task, the number of strong hands ought to be equal to the number of the great minds involved — if not greater.

Kiss of the Oceans is on display through Jan. 4 at the Flagler Museum on Palm Beach. Admission is free with a museum admission; adult tickets are $18. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. Call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.