If you were a member of the prosperous middle class of Leipzig in the early part of the 18th century, chances are you’d have made it over to the Catharinenstrasse on a wintry Friday night to catch the cantor of the city’s St. Thomas Church, one Johann Sebastian Bach, holding forth at the head of an instrumental ensemble playing some of the best new music of the time.

You’d have heard J.S. Bach and his collegium musicum at a coffeehouse called Café Zimmerman, where the merchant Gottfried Zimmerman served his fellow Saxons their favorite beverage and hosted musical performances there and in his outdoor coffee garden in the summer. Bach directed at least 60 concerts annually at Zimmerman’s from 1729 to 1739, at a time when he has usually been considered to be focusing on sacred music.

“I think it was pretty chaotic by our standards … there were often 100 people at the coffeehouse in a space that was not that large,” said Jeannette Sorrell, founder of Apollo’s Fire, a Cleveland-based Baroque orchestra. “There is a lovely painting of Bach leading a small orchestra gathered around a harpsichord, and there are two ladies in rocking chairs with coffee that seem to be chatting, and there are dogs and people running around. I just think it was a pretty wild scene.”

This weekend, Sorrell comes to Miami Beach for two concerts to conduct the the New World Symphony and preside at the harpsichord in a program called “A Night at Bach’s Coffeehouse,” featuring the Brandenburg Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 and the sinfonia from Cantata No. 42 (Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats), as well as a suite from Handel’s ballet Terpsichore, and two works by Vivaldi: a concerto for two cellos (in G minor, RV 531) and Sorrell’s own arrangement of a trio sonata (in D minor, RV 63) based on “La Folia,” the 15th-century Portuguese pop tune that composers all the way down to Rachmaninov have used as the basis of extended works.

In her concerts Saturday night and Sunday afternoon at the New World Center, Sorrell says she’ll be trying to re-create the atmosphere of those long-ago Leipzig jam sessions.

But without the dogs, she’s careful to note.

“We are going to be able to evoke much of the spirit of those concerts in the sense that those concerts were built around Bach’s very youthful orchestra, the collegium musicum. It was an ensemble of students at the university, and they were very spirited and played there because they wanted to,” she said. “They were not paid an enormous amount of money to be there.

“And the New World Symphony is a group of extremely talented young people who are very dedicated and who want to be there,” Sorrell said. “I feel the kind of youthful energy we will have (for the concerts) is exactly what Bach had in mind.”

Sorrell herself is celebrated for the energy and vigor of her performances at the head of Apollo’s Fire, which she founded in 1992. The group has released 20 recordings on Britain’s Avie label, four of which have been Top 10 sellers on the Billboard classical charts, including the complete Brandenburg Concertos and harpsichord concertos of J.S. Bach (2010), Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 (2010), and two crossover records, Come to the River: An Early American Gathering (2011) and Sacrum Mysterium: A Celtic Christmas Vespers (2012).

The group’s discography also includes four Mozart recordings, discs of music by Telemann and Michael Praetorius, Handel’s Messiah and a survey of folk tunes from the British Isles. Its current season has included the Handel and the Monteverdi, and last month, Apollo’s Fire performed a program called “Blues Café 1610,” in which singers and instrumentalists jammed on the popular songs of the early 17th century.

Later this year, the group will release two more recordings, and this summer it makes its debut at two major music festivals: Tanglewood, and the Proms, London’s all-summer-long classical celebration at the Royal Albert Hall.

The daughter of two academics, Sorrell grew in up in Northern California and the Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia, and knew from her teenage years that she wanted to direct an early music ensemble. She studied at the Oberlin Conservatory and was in the conducting courses at the Aspen and Tanglewood festivals, where she worked with Leonard Bernstein, Robert Spano of the Atlanta Symphony, and British early-music specialist Roger Norrington.

“I knew from the age of 17 that that was what I wanted to do. Even at Tanglewood — I was only 24, so I was the baby of the class — I was already 100 percent, totally convinced that I wanted to have a chamber orchestra with period instruments,” she said. “And it was just a question of: Will I be able to do it? Will I have the chance to do it? But I knew that’s what I wanted.

“In high school, that was the time in the mid-’80s when the recordings of period instrument orchestras were coming out from Europe. And I just loved the colors of the instruments — the transparent sounds of the strings, the colorful woodwinds — and I think I just responded to it on a really gut level.”

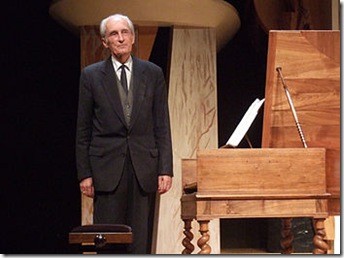

Norrington offered her the chance to work for him in London after Tanglewood, but Sorrell chose instead to go to Amsterdam for a year of study with the great Dutch harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt (1928-2012), a musician who was in the forefront of the early music revival and himself directed a splendid account of the Brandenburgs.

“Leonhardt was a man of few words, but I thought that every word that came out of his mouth was perfectly chosen. In six words, he could convey something more clearly and articulately than I could do in 12 sentences,” Sorrell said. “But the best part about it, because he was a man of few words, what he mostly did was, I would play my pieces for him, and then he would sit down and play them for me. Not saying much, but just playing it.

“And for me personally, that was probably the best way of learning how to make the best sound on the harpsichord; how to transcend the limitations of the harpsichord; how to create the illusion of dynamics; how to make Baroque music expressive; how to liberate yourself from the fact that very little of the expression is written on the page, but that doesn’t mean it’s not meant to be there,” she said.

“After my lessons would finish, I would sit down on his front step on the canal in Amsterdam, and just try to write down everything that he said,” she says, laughing.

Leonhardt was also a tough taskmaster in his lesson requirements. All of his students had to show up for their weekly lessons with 40 minutes of music. “And get this: He never wanted to hear anything twice. We were basically bringing half a recital program to every lesson,” she said. But that demand helped her learn a great deal of new repertoire in a hurry (“I was locked in my studio apartment in Amsterdam learning the complete variations of Sweelinck”), a valuable skill for her future as a conductor in addition to the seriousness of the training he gave her.

“The depth I feel I was able to absorb from him has been just so important on a fundamental level,” she said.

For this weekend’s concerts, Sorrell plans to get the New World playing like a Baroque orchestra without having to use period instruments.

“I’ve had the experience before, particularly at Oberlin Conservatory and a little bit at CIM (the Cleveland Institute of Music) of being able to really roll up my sleeves and get a modern orchestra to sound like period instruments. If they’re young and flexible and at a high level, which of course the New World absolutely is, it can be done if you have enough rehearsal time,” she said, noting that she’s getting a generous amount of rehearsals — seven — with the orchestral academy.

“So I think it will be really fun to see whether audience members think: Whoa, are they playing on period instruments? …. So that’s my secret little goal.”

Playing in Baroque style was once a novelty or for specialists only, but today’s orchestral player has to be just as conversant with its norms as any other style.

“These days, the level of stylistic understanding for Baroque music that is expected of principal players in major orchestras is much, much higher than it was 10 years ago,” Sorrell said. “In the past few years, I’ve been working with the Pittsburgh Symphony, and the Seattle Symphony, and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and all three of those have concertmasters who can completely sound like they’re playing a Baroque violin, even though it’s a modern violin. Also, the Omaha Symphony. Same way.

“Not everybody in the orchestra has that knowledge and training, but the principal players, they do. And so I really think this is an important skill set for young players like the New World Symphony to have in their toolbag.”

Sorrell’s approach is distinguished by its sheer joy in making music, in contrast to the sometimes overly reverent style of early music presentation she encountered as a youth.

“I’m the daughter of two professors, and I grew up in an academic environment. I went to a ton of concerts when I was growing up, and the early music concerts were attended by 47 people in a college chapel, and 43 of them had Ph.D.’s,” she said. “And that has never been what I wanted to do with my life, give concerts for 43 Ph.D.’s in a college chapel. I think it’s lovely and I’m glad it happened, and it’s so important that the early music revival happened, and we’re so indebted to the generation of pioneers that made it happen.

“But thanks to the fact that they did that, I don’t feel that needs to be our mission now. And what I’ve always wanted to do is bring music to a mainstream audience, and introduce Monteverdi and Caccini and Purcell to new audiences, because they will respond on an emotional level, and love it,” she said.

Central to that idea, and to her work with Apollo’s Fire, is the concept of Affekt, the Baroque-era theory of illustrating the passions through the arts.

“The most distinctive thing about the Apollo’s Fire style is that we are really focused on the concept of Affekt, and the idea that the music is there to move the emotional mood of the listeners. We’re very conscious about trying to find the emotional drift of any particular phrase, and the rhetorical tools that the composer is using in any phrase: Is this a phrase where we’re trying to keep the audience in suspense, or is this a phrase where we’re trying to calm them down? Or is this a phrase where we are creating a bit of agitation?

“We try to be very focused on how we project those things, so that the experience is an emotional one both for the people on stage and in the seats,” she said.

That extends to the Vivaldi on this weekend’s concerts. Sorrell said she liked the priestly Venetian’s setting of the dance tune best of the many composers who used it, but his version was a trio sonata for two violins and continuo, which made it too small for use by Apollo’s Fire.

“It was sad that it was only for three players, and I wanted more of our group to be able to join in the fray,” she said, and so she transformed it into a concerto grosso. “We played it several times with Apollo’s Fire and it was amazing: It seemed to really grip the audience. Eventually, we ended up memorizing it and we play on tour these days from memory.

“But the main thing I’d like to convey to the audience is that all of the ‘La Folia’ variations written by all the different composers have one thing in common, which is that they get faster and wilder toward the end,” Sorrell said. “That’s because ‘Folia’ means ‘madness’ … so we want to bring out that quality of hysteria and madness as it reaches its climax.”

Sorrell’s visit to Miami Beach is her first appearance in South Florida since 2008, when Apollo’s Fire came to the Miami Bach Society’s Tropical Baroque Festival. This month also marks the 330th anniversary of Bach’s birth, which provides a good reason to ask her to explain the sources of Bach’s power.

“(A) quality of spirituality and feeling is just so pervasive in Bach, and it’s not only in his sacred music. Every note he wrote for every purpose, there’s still that quality there. I think it’s summed by something that was reported to us by his son, C.P.E. Bach. Someone asked J.S. Bach, ‘What is the purpose of the basso continuo?’ Which is kind of a technical question, and you would expect some kind of technical answer.

“And Bach’s answer was, ‘The purpose of the basso continuo, as is the purpose of all music, is the glory of God and the refreshment of the spirit.’ Which is to say that every note of the music, whether it’s the bass line or any other note, whether it’s played by the violas or whoever, every note is there for the glory of God and the refreshment of the spirit.

“And I’m not even a regular church-going person, but it doesn’t matter. I think we feel that in the music and we respond to it.”

Jeannette Sorrell conducts the New World Symphony at the New World Center in Miami Beach at 7:30 p.m. Saturday and 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets start at $39; call 305-673-3331 or visit www.nws.edu.