It is almost a cliché that famous writers and alcohol go together.

It is almost a cliché that famous writers and alcohol go together.

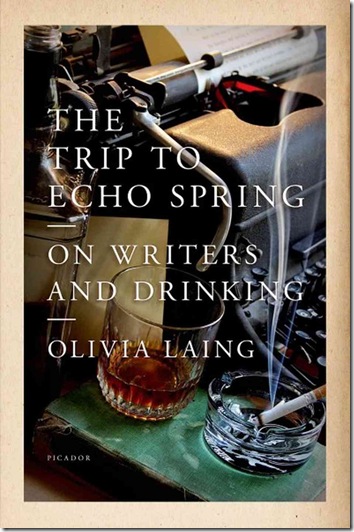

In this important new book English author Olivia Laing focuses on six prominent American writers who struggled with alcoholism — F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman and Raymond Carver. Laing grew up in an alcoholic family, which partly explains her intense interest in the subject.

She set out to explore the intersection of writing, drinking and childhood experience. It is no surprise that fiction often draws on authors’ early memories. Some authors also claim that liquor helps them write, although as Laing makes clear, alcohol more often damages minds and bodies.

Of the six profiled writers, two committed suicide (Hemingway and Berryman). Four died before the age of 60.

Laing pored over the writers’ books, read their journals and notebooks, and dug deeply into the causes and effects of alcohol abuse.

Alcoholics are experts at denial and deception. Fitzgerald sometimes would claim he was not drinking, meaning he was not consuming gin, while consuming 20 bottles of beer a day. “When I drink, it heightens my emotions and I put it in a story,” he said. “My stories written when sober are stupid.”

Hemingway, who lived in Key West with Pauline Pfeiffer, his second of four wives, in the 1930s, “maintained an unshakable belief in alcohol’s essential beneficence, its ability to nourish and uplift,” Laing writes. He suffered from depression and wild swings in temper, and killed himself with a gun at age 61.

All six authors tried at times to stop drinking, but only two succeeded (Carver and Cheever). After decades of getting drunk, Cheever stayed in recovery for his final seven years. Cancer killed him at age 70.

Carver, who died at age 50 of lung cancer, said in a published interview, “Toward the end of my drinking career, I was completely out of control and in a very grave place. Blackouts, the whole business — points where you can’t remember anything you say or do during a certain period of time … You’re on some kind of automatic pilot.”

Laing cites research on the causes of alcoholism, which largely remain a mystery. Possible factors include personality traits, early life experiences, societal influences, genetic predisposition and abnormal brain chemistry.

Laing shines as a prose artist, particularly when describing scenes she encountered as she traveled across the country visiting the haunts of the profiled writers. She admires twilight in Manhattan, “On its way to darkness, the sky had turned an astonishing, deepening blue, flooding with colour as abruptly as if someone had opened a sluice.”

That said, her attempt to weave a travelogue into the story seems forced. The book also suffers at times from disorganization as the author skips back and forth among writers and subjects.

The title comes from Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, when the alcoholic son, Brick, says to his father, Big Daddy, “I’m takin’ a little short trip to Echo Spring,” referring to a brand of bourbon stashed in a nearby liquor cabinet.

Williams suggested that his alcoholism might have been responsible for the haphazard nature of his later plays. He may have suffered from a form of aphasia in which long-term alcoholics have trouble retrieving words and creating sentences.

Laing never stoops to judgment or blame, offering instead a rigorous study of these writers and their alcoholism. Can drinking sometimes unleash the creative mind? The Trip to Echo Spring does not offer a definitive answer. While cataloguing alcohol’s crippling toll, Laing also says the profiled authors produced “some of the most beautiful writing this world has ever seen.”

The link between alcoholism and writing is not a new subject and Laing has not written the definitive book on it, but she has given readers — and authors — much to ponder.