For many, the biggest surprise from this year’s Oscar telecast was not Hugh Jackman’s better-than-average hosting job or the upset victory of Departures for Best Foreign Language Film.

It was the inclusion of critic Manny Farber in the montage of recently deceased cinematic luminaries. For me, watching Farber’s outsider name fade in, and seconds later fade out, on the onstage projection screen amid pictures of insider Hollywood figures, the moment was tarnished a bit by the tepid response, the crowd obviously holding much of its applause until Paul Newman’s name lit up the screen.

I should have been pleased as punch Farber’s name appeared there at all.

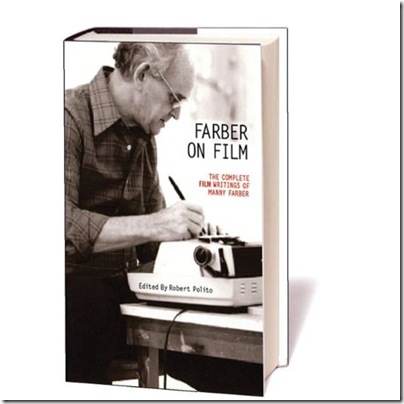

“A lot of us of were surprised,” said Robert Polito, a writing professor at New York’s New School who’s just edited a mammoth compilation of Farber’s work titled Farber on Film. “Patricia [Patterson, Farber’s wife and fellow critic] knew about it a couple days in advance, because they asked her for photographs. I would love to know how that came about. Howard Hampton pointed out that you couldn’t have a less likely Oscar film critic than Manny Farber. One shorthand way of defining White Elephant Art would be to submit a list of Oscar winners.”

Polito, who will speak and sign copies of the book this weekend at the Miami Book Fair, was referring to one of Farber’s seminal essays, White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art, which divided movies – or moments within movies — roughly between the kind of shambolic, rough-hewn, burrowing style that “eats its own boundaries” and the self-conscious, heavily stylized masterpiece art, “reminiscent of the enameled tobacco humidors and wooden lawn ponies bought at white elephant auctions decades ago.”

It’s obvious reading this 1962 essay, as relevant today as it’s ever been, where Farber stood. Emerging from the new wave of American film criticism alongside James Agee, Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, Farber has had the longtime reputation of championing B-movie directors from the classic Hollywood studio system, reverentially admiring the underground films of William Wellman, Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray as fervently as he would a piece of modern art (Farber was a notable painter, as well, which helps explain his frequent obsession with mise-en-scène and spatial interaction over story and character).

But Polito’s 800-page collection goes a long way to expand our understanding of Farber beyond his most cited essays. Polito, a longtime admirer who first met Farber in 1999 under the auspices of a magazine feature that never panned out, remained friends with the critic until his death nine years later, and his resultant work collects Farber’s complete writings from 1942 to 1977, save for Farber’s short stint at Time in 1949, where his work was supposedly butchered. Farber on Film more than doubles the amount of material previously available on the long out-of-print Farber collection Negative Space.

under the auspices of a magazine feature that never panned out, remained friends with the critic until his death nine years later, and his resultant work collects Farber’s complete writings from 1942 to 1977, save for Farber’s short stint at Time in 1949, where his work was supposedly butchered. Farber on Film more than doubles the amount of material previously available on the long out-of-print Farber collection Negative Space.

“A lot of this book was new to me,” Polito said. “Manny’s reputation is for those kind of long, serpentine essays that he did in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. The assumption was that he was relatively careless about the more conventional items of plot or character, but it turns out if you read the work chronologically, you watch those essays arise out of the weekly context that preceded him, moving toward those essays and the conceptions behind them. But you also get to see him, secondly, as extremely good at finding ways to render the plot of a movie without the piece just kind of stopping.”

He’s not himself right away, Polito added. “It takes a year or so to suss all that out. But it’s amazing to me how much of what we think of Farber is there right from the start. One of the other surprises too, but perhaps shouldn’t have been, is that everything seems to have been always in flux and in process for many years. He rarely if ever possessed static opinions on anything.

“You think you know from later essays what he supposedly thought about The Best Years of Our Lives or Frank Sinatra or Preston Sturges, but the earlier pieces are in clear conversation and contradiction with those later opinions. What you’re watching is that constant sense of reevaluation that animates the individual essays and reviews. He’s always coming back and looking from another angle.”

Farber’s ability to see beyond the surface and ferret out nuance like one of his beloved termite artists would probably deem him unfit in the polarized world of mainstream movie writing today. Always looking at works anew and capturing them in all their complexity, Farber rarely loved or hated films unconditionally. His writing and opinions would never fit a star-rating, thumbs-up or thumbs-down paradigm.

“Arriving at an opinion is never his goal,” Polito said. “His goal is something like accuracy, and for him accuracy ultimately calls for multiple points of view. Film studies, with obviously rare instances, isn’t so much about looking and seeing. It’s about sociology, anthropology, history. Manny was about something else.

“And what’s fascinating too, is that there’s a culture of opposition between film reviews and film theory. Manny is in neither of those camps, but he exemplifies the best of both. He had lots of powerful, implicit theoretical positions about looking and seeing and even the mimetic relationship between the movie he’s writing about and his own prose, that I think links Manny to the great film theorists of the 20th century.”

But while much film theory can be a laborious chore to slog through — as much as I love reading Roland Barthes’ academic theories on semiotics, they hardly lend themselves to witty wordplay — every Farber review, even for films that are minor and forgotten (and there are many of those in Farber on Film), contains literary jewels that transcend mere criticism.

“Manny is one of very few critics that you keep reading even if you have no idea of the work he’s writing about,” Polito said. “It grabs you as writing and grabs you as thinking, so that you’re watching his mind move on the page.”

He calls Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp “a pushover for a puff of wind,” and claims Frank Capra’s “nervous films skip goat-fashion over a rocky Satevepost terrain.” I don’t even know what that means, but it sounds great. It’s no surprise that Polito, an accomplished poet, would be as inspired by Farber’s prose as much as his insights.

The influence of Farber can be seen all over the critical map today, not so much in major newspapers but in alternative weeklies and film journals (J. Hoberman, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Gonzalez, Amy Taubin and Kent Jones are worthy heirs). Modern filmmakers, too, have absorbed Farber’s theories into their work; in a blurb on the jacket of Farber on Film, Martin Scorsese beams that he’s reserved a spot on his shelf for the book.

Maybe this ultimately explains why Farber deserved as large a place as any on that Oscar death list. It’s unlikely anyone who passed away in 2008 contributed more to the idea of film as an art form than Manny Farber.

John Thomason is a freelance writer based in South Florida.

Robert Polito will discuss Farber on Film at 3:30 p.m. Saturday at the Miami Book Fair, 401 NE 2nd Ave., Miami. Polito also will read some of his poetry at noon Sunday. Admission is $10, and includes admittance to all lectures and signings. For information, call 305-237-3258.