After the Bible, the Tao Te Ching is the second most translated text in the world, and certainly it is the most famous and influential book of ancient Chinese wisdom in the West. Why, then, with dozens of versions already available, would we need a new one – especially by a translator who made his name in classical Japanese samurai literature?

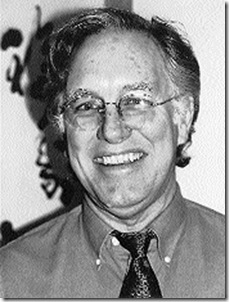

“My friends all ask that same question,” says William Scott Wilson, the renowned translator of Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai, The Unfettered Mind: Writings of the Zen Master to the Sword Master, and The Book of the Five Rings, among other medieval samurai classics.

One reason, says Wilson, who grew up in Fort Lauderdale and now lives in Miami, is the deep connection between the Tao and Zen Buddhism, which, in turn exerts a strong influence on the Japanese martial arts tradition. In a way, he says, all his samurai translations have led him back in time toward the Tao Te Ching.

“Going on to the ‘Tao’ is like going to the source of sources,” Wilson says. “I always wanted to do this, but didn’t think anyone would pay me to do it. It’s one of the three great Chinese books: The Tao, the I Ching and the Analects of Confucius.”

“Going on to the ‘Tao’ is like going to the source of sources,” Wilson says. “I always wanted to do this, but didn’t think anyone would pay me to do it. It’s one of the three great Chinese books: The Tao, the I Ching and the Analects of Confucius.”

Born in 1944, Wilson was a political science major at Dartmouth in 1966 when a friend invited him on a three-month kayak trip along the coast of Japan. “That trip was an eye-opener,” says Wilson. “I didn’t know what was there for me, but I knew it was something.”

Wilson earned a bachelor’s in Japanese literature and language at the Monterey Institute of Foreign Studies in Monterey, Calif. He studied Edo period philosophy at the Aichi Prefectural University in Nagoya, Japan. He translated his first book, Hagakure, an 18th-century martial arts classic, to fulfill an academic requirement – with no thought it might be published.

But since being published by Kodansha in 1979, Hagakure has never been out of print. While he’s had to supplement his income with other jobs, Wilson has steadily built up a body of classical samurai translations. “I’ve made sacrifices to do what I love,” Wilson says. “You do what you can to keep doing this. I’ve been fortunate in recent years, when Kodansha issued new editions of all my books. They look really nice.”

Wilson’s big break came in 1999, when indie film director Jim Jarmusch made the Zen thriller Ghost Dog, starring Forest Whitaker as a mob hit man who reads Hagakure and lives by its warrior code. After the movie came out, sales for Hagakure went “way up and remained up for years,” Wilson says.

Gradually Wilson’s interest expanded beyond samurai literature to related fields – first to Nō drama (The Flowering Spirit: Classic Teachings on the Art of Nō; 2006), then to ancient Chinese maxims (The 36 Secret Strategies of the Martial Arts, ancient sayings collected by Hiroshi Moriya; 2008) and ancient Chinese philosophy (The Unencumbered Sprit, by Hung Ying-ming, published earlier this year.)

Because classical Japanese writing is derived from Chinese, Wilson had to study both languages, and therefore is qualified to translate each. “I picked Chinese as my second language for my master’s,” he says. “I wanted to learn to read Chinese. It’s just a beautiful, wonderful language.”

Because classical Japanese writing is derived from Chinese, Wilson had to study both languages, and therefore is qualified to translate each. “I picked Chinese as my second language for my master’s,” he says. “I wanted to learn to read Chinese. It’s just a beautiful, wonderful language.”

Wilson is one of those rare people who seem born with a gift for languages. In high school he taught himself Spanish in six weeks “for fun.” To illustrate a point about the Chinese concept of “te” and how it’s related to the English word “virtue,” he recites a few lines from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales – in what sounds like flawless Middle English.

What really distinguishes Wilson’s translation of the Tao is his attempt to push it 300 years deeper into antiquity. Written about 500 B.C., supposedly by the legendary sage Lao Tzu, the Tao exists only in the “new” text of 200 B.C. Wilson wondered what he might get if he recast the text into the archaic characters in use at the time the original was written.

“I said, ‘Let’s go back to the source,’ ” Wilson says. “I had books with ancient characters and etymology. Maybe I could find new meaning, or at least nuance, if I can translate it as it might appear to its first readers.”

Much of Wilson’s version is similar to existing translations, but he does find nuance, if not altogether new meaning, in the archaic characters. For example, one of the key principles of the Tao is to “act without acting, to go on intuition rather than rationality,” Wilson says. “If we think we have it, we don’t.”

One version of that thought, which repeats throughout the Tao, is to act without relying on anything. Through the use of archaic characters, Wilson realized the word usually translated as “act” is closely related to the word for “fabricate,” which allows for a fine adjustment in connotation.

“I used the word ‘fabricate’ instead of ‘act’ in the theatrical sense,” Wilson says. “That was the revelation: It doesn’t just mean mindless acting. It means act without making something up. Whoever put this book together felt strongly about this idea. It’s one of the lodestones of the ‘Tao.’ ”

Wilson’s translations of classical Japanese – and now Chinese – literature have proven so distinguished they have been translated themselves into 18 languages, including Magyar, Lithuanian, and, in some cases, modern Chinese — which, ironically, Wilson cannot read.

“Modern Chinese has been simplified down so much I won’t even look at it,” Wilson says. “It’s lost all its charm. The Communists ordered it made so simplified they wiped out 2,000 years of Chinese literature. All it’s good for is Communist propaganda.”

Still, Wilson is grateful for every translation. Take the Magyar edition of Hagakure, which earned him, in total, a check for $66: “If I hadn’t been so broke, I would have framed the check and hung it on my wall.”

Chauncey Mabe is the former books editor of the Sun-Sentinel. He can be reached at cmabe55@yahoo.com. Visit him on Facebook.