By Lucy Lazarony

A current exhibit of artwork at the Delray Beach Public Library is the product of an effort by a local group of Holocaust survivor relatives to bear witness to one of the defining tragedies of the 20th century.

The GenZ Project, an endeavor by Boynton Beach-based NextGenerations.org, connects college students with survivors of the Holocaust to create pieces of art inspired by the memories and stories of those who lived through the anti-Jewish persecutions of World War II.

Sylvia Kahana, who is the daughter of two Holocaust survivors, reached out to Christopher Burlini of Burlini Studios in Boca Raton to become involved with the GenZ Project.

“I didn’t hesitate,” Burlini says, and as part of his involvement, attended a GenZ workshop at Nova Southeastern University.

“That was my first experience listening to a Holocaust survivor. I was beyond moved. That was really amazing and eye-opening,” he says.

Burlini encouraged college students to come and create their story expressions at his studio for free. “These aren’t artists. These are kids with a passion,” he says.

He also encouraged his own students to create their own works of art with Jewish and Holocaust themes. “You can paint whatever you want,” Burlini told his students. “We’re looking for hope on the other side and change.”

The result is a moving 50-piece exhibit on display through March 13 at the library. Artists worked in oil, acrylic and watercolor to create artworks with titles such as Left Behind, To Life and Dreams of Tomorrow.

Bea Doom Merena’s beatific oil painting of a young girl asks, Because I Survived What Did I Become?

“We saw a lot of release through the artwork,” Burlini says.

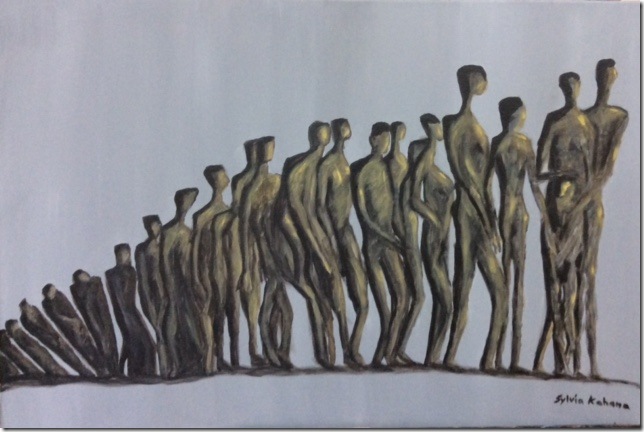

Kahana’s two paintings are called Release and Never Forgotten.

For Kahana, Release means breaking free of the “imprisonment, and the heartache and the tears of blood and barbed wire. The survivors were released, coming forward from prison life to this second chance that keeps going for generations.”

Kahana’s Never Forgotten was inspired by a Holocaust memorial she saw in Moscow five years ago. Her aim was to capture the resilience of Holocaust survivors.

Kahana’s parents are Holocaust survivors from Warsaw, Poland.

“My mother was one of eight and four survived. My father was the youngest of 14 and the only survivor,” Kahana says. “Even though the Holocaust was part of my upbringing, my parents focused on the triumph and survival.”

Artist Gustavo Saslafsky was born 13 years after the Holocaust in Argentina. With his painting I Am, Saslafsky “wanted to do something, starting with sadness and going into life.” The word “love” is written in six languages.

I Am is inspired by Prague’s Lennon Wall, a wall of graffiti begun to honor John Lennon. Saslafsky visited Prague last summer, and began the painting originally as a project to work on with his children. He began adding words and images related to the Holocaust when Burlini told him about the project in December.

“I felt the connection. Every day, I would write something and come back with something,” Saslafsky says.

There is the darkened tower of a concentration camp, a photo of arm tattooed with numbers, and photo of young children in striped uniforms.

“I wrote “innocence lost” because of the innocence lost of those kids,” Saslafsky says.

Holocaust survivors added their names and their messages to I Am at the exhibit’s opening at the Burlini Studio on Jan. 17. More than 500 people attended.

“At the end of the show, the survivors came up and wrote their names and wrote their messages. That was something very special,” Saslafsky says.

Performing at the event was a musical band made up of Holocaust survivors. They walked up to Saslafsky’s painting, grabbed a white pen and wrote on the black tower of the concentration camp.

“They wrote right in the middle in white. It felt like they brought it to life,” Saslafsky says.

“One of them is 89 years old. He jumped down from the podium like a little boy.”

The GenZ Project has brought Holocaust survivors to speak with college students at Florida Atlantic University, Lynn University, Nova Southeastern University and Broward College.

“It teaches people what can happen if we don’t stand up to hatred,” says Abraham Mercado, who is studying film and Jewish studies at Florida Atlantic University.

Mercado, 24, is a GenZ volunteer and has created a film promoting what GenZ does.

“I’ve had the privilege of interviewing 20 to 25 Holocaust survivors,” Mercado says. “They really, really wanted young people to hear their stories. They were eager to teach young people what happened.

“These survivors still are happy living their lives. They’re trying to make life better for others,” Mercado says. “They tell people, ‘Look, we have the chance to be better human beings.’

“The last workshop we filmed at Nova, I think there were 150 people there,” Mercado says. “When you see a Holocaust survivor speaking in front of the crowd, it is 100 percent completely quiet when a survivor is speaking. You know, these students, the first thing they do when they go back home is hug their mother.”

Joseph and Mary Eckstein of Boca Raton are two Holocaust survivors who share their stories with college students through the GenZ Project. Both are from Budapest.

“It really is amazing what they get out of our experiences. They understand it,” Mary Eckstein says. “The student expressions, the pieces are just incredible. I think it’s a very good way for them to express their feelings after hearing the story of what we went through. And the pieces they create show they understand it.”

The GenZ website features an online gallery (at genzproject.org) of story expressions created by college students.

“Hopefully, they will learn from it,” Eckstein says. By creating pieces of art, it becomes part of them. It’s not something they forget.”

The Ecksteins also share their stories with students in local public schools.

“They younger generations, the American young students, grew up with food. Even the poorest one has more. They don’t know what forums hatred can take,” Mary Eckstein says. “We went through experiences where people were killed simply because of who they were.”

Eight-year-old Mary was not taken to the camps and was able to live in a protective apartment with her mother in Budapest.

“My mother and I somehow managed to survive,” Mary Eckstein says.

Joseph Eckstein and his whole family were taken to Auschwitz. He was 15 at the time.

“He has a number tattooed on his arm,” says Mary Eckstein of her husband of 59 years.

On his first night at the camp, he saw a chimney smoking in the middle of the night. He asked a guard: What kind of factory runs at night? He was told, “That smoke, that’s your family.”

The teenaged Eckstein spoke German and he avoided the death march from Auschwitz by hiding in an attic with a few other kids.

“We survived for one reason only: To make sure we talk about it and make sure it never happens again,” Mary Eckstein says.

The Delray Beach Public Library, 100 W. Atlantic Ave., is open from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Wednesday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday through Saturday, and 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Call 266-0194 for more information or visit www.delraylibrary.org.