Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) is known for pretty pictures of women and children, the kind of pictures that make people smile and sigh a lot.

But what many don’t know is that, as a working female artist living in late 19th-century Paris, she was a maverick. A driven woman who personally balked at convention, she remained single and childless, apparently by choice, so that she could pursue art as a career. Professionally, she kept her work fresh and original by working against the grain.

Mary Cassatt: Works on Paper, organized by the Adelson Galleries of New York for the Boca Raton Museum of Art, presents a small, yet significant, selection of h er vast oeuvre. The 41 works, drawn from the collection of Ambroise Vollard, establish Cassatt as a skilled draftswoman and printmaker. Featured are drypoints, aquatints, drawings, and rare pastel counterproofs. These works show that Cassatt had an innate drive towards perfection and a commitment to learn avant-garde techniques.

er vast oeuvre. The 41 works, drawn from the collection of Ambroise Vollard, establish Cassatt as a skilled draftswoman and printmaker. Featured are drypoints, aquatints, drawings, and rare pastel counterproofs. These works show that Cassatt had an innate drive towards perfection and a commitment to learn avant-garde techniques.

As a woman, Cassatt seemed inherently inclined to live countercurrent to societal expectations. Born in Philadelphia to a wealthy family, at 15 she began studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In 1863, at age 18, she announced her desire to move to Paris. Her father refused, and then acquiesced. She wanted European training and knew that recognition from the Paris art world was central to her future success.

The result: she ultimately became one of the few women – and the only American – embraced as a French Impressionist.

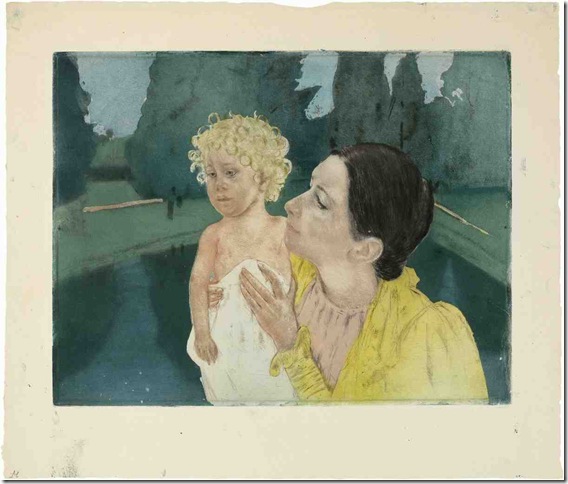

In this exhibit, devotees of Cassatt’s painting can see the depth of her skill at portraiture in the details of her prints and drawings. On the surface, the women and children are serene. Cassatt seemed captivated by motherhood, so it’s puzzling she never married and had children of her own. Her women are depicted with grace. But is their stillness serenity or boredom? Clearly, they exhibit a sense of duty. But are they happy, or just complacent?

We know that Cassatt was restless. One wonders if her bohemian lifestyle prompted her to see other women’s lives as restrictive, or if she was envious. Cassatt’s women fulfill societal expectations. They dress in beautiful, yet restrictive garments (this was the age of the corset). They drink tea. They devote themselves to motherhood. They gaze blankly at children who upstage them. Is this wry commentary?

Cassatt was unconventional in her technique, if not her subject matter. Many of the exhibited works are drypoint, which shows her distaste for mass production. Drypoint uses a sharp stylus or needle to scratch lines directly into a copper plate. It is easier for an artist to master than engraving because using the needle is closer to using a pencil. But one can only print a small amount from the plates. Artists such as Cassatt used drypoint because they preferred a small number of handmade images rather than hundreds of identical ones.

Atypically, she made multiple prints of the various stages of her work and used multiple plates prior to completion, as evidenced in The Mandolin Player (1889-90), which is seen here in the second of its seven states. But her methods attracted praise. She was gaining such notoriety as a skilled and unparalleled printmaker that in 1889 she participated in the first exhibition of the Société de Peintres-Graveurs – founded to promote original prints. The same year she also attended a massive exhibit of Japanese woodcut prints at the École des Beaux-Arts. This resulted in new stylistic exploration.

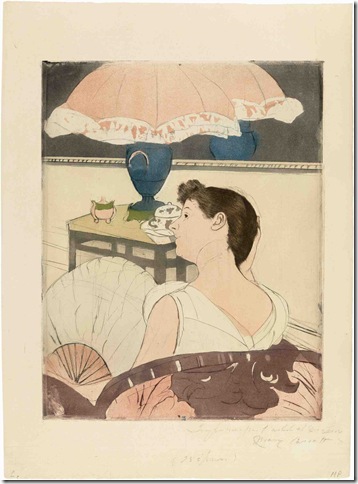

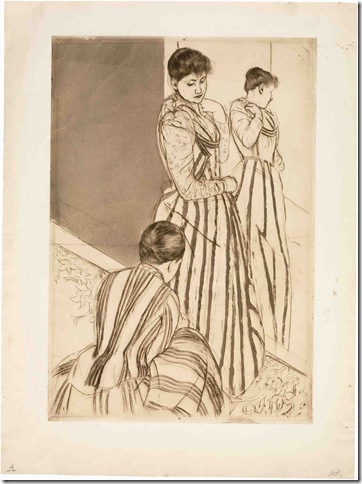

Inspired by the Japanese simplicity, clarity and bold color, Cassatt produced 10 aquatints known as her “group of 10.” Art historian and Cassatt scholar Adelyn Breeskin, remarked that these prints, “…now stand as her most original contribution … adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts … technically, as color prints, they have never been surpassed.” What a delight, then, that three of the 10 are part of this exhibit: The Fitting (1890-91), The Lamp (1890-91) , and Afternoon Tea Party (1890-91)

Cassatt meticulously applied color to the copper plates for each print in order to control the final effect, which somewhat mirrors a woodcut. Other Japanese elements are notable in The Fitting. There is boldness and two-dimensionality to the composition. The forms are defined and delineated. One of the women is portrayed from behind — a Japanese perspective. Flat areas, rather than shading, control depth, and decorative patterns are brought to the foreground. The same qualities are evident in The Lamp, though here viewers see the exact influence of Japanese woodblock print colors, which are boldly geometric, yet muted.

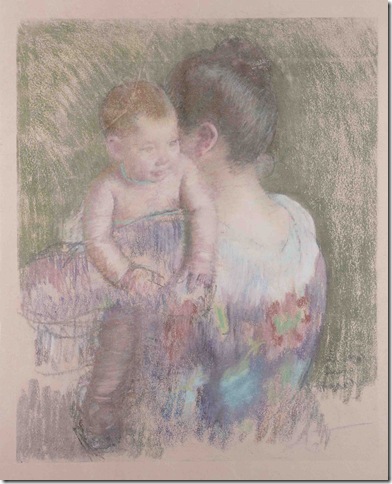

The final prints in the exhibit are pastel counterproofs and confirm that by 1899 Cassatt had returned to her former style, evidenced in their shading, depth, and three-dimensionality. Counterproofs are made by placing a damp sheet of paper on top of a pastel and applying pressure.

Cassatt’s pastels were inspired by Degas. Like him, she was chiefly interested in figure compositions. In Baby Charles Looking Over His Mother’s Shoulder (1900), Cassatt’s linear pastel marks and lit-from-above-luminosity mimic Degas. And it was Degas who encouraged Cassatt to make counterproofs.

Mary Cassatt: Works on Paper is intimately engaging because we are peeking into Cassatt’s mind. Seeing her prints in various stages of completion, we witness her process and focus. Her steadiness, progression, and patience shine through in her skillful renderings. But to gain this skill she persevered during an era that restricted women’s opportunities — preferring them to just look and act pretty.

Ironically, Cassatt’s depictions of this norm led to success, even though she herself didn’t comply. Knowing this adds another layer of brilliance to work that can certainly stand on its own.

Jenifer A. Vogt is a marketing communications professional and resident of Boca Raton. She’s been enamored with American painting for the past 20 years.

Mary Cassatt: Works on Paper is on view at The Boca Raton Museum of Art until April 11, 2010. Special hours for this exhibition are Tuesday, Thursday and Friday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.; Wednesdays 10 a.m.-9 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday 12 p.m. – 5 p.m. Admission is $14 for adults, $12 for senior citizens (65 and older), $6 for students and $10 per person for group tours. For more information call 561-392-2500 or visit www.bocamuseum.org.