Gian-Carlo Menotti’s The Consul was a Broadway sensation in 1950, but in the decades since it’s dropped below the operatic radar.

The current production by Florida Grand Opera of this Cold War work is as good an argument as can be made that the opera deserves to be restored to the mainstream, if not so much for the greatness of its score as its sheer effectiveness as theater.

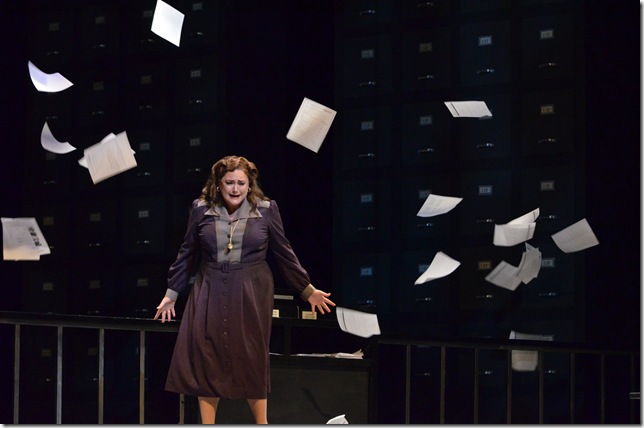

In a powerfully atmospheric but simple production borrowed from Seattle Opera, Florida Grand Opera closes its 74th season on a remarkably effective note with a very strong cast headed by Kara Shay Thomson as Magda Sorel, whose performance of the Act II soliloquy “To this we’ve come” was beautifully done and won a long and sustained ovation from the relatively small house gathered Sunday afternoon at Miami’s Ziff Ballet Opera House.

But what was most impressive overall was how strong The Consul is dramatically. Menotti wrote his own libretto, as he always did, and what he demonstrates here is a sure hand at keeping an audience engaged. Some of the new operas I’ve seen tend to be overly earnest, trying too hard to make a statement, and leaving the action somewhat boxed in as a consequence. But Menotti knows how to entertain: the Act II appearance of the Magician, for instance, looks almost embarrassing on paper, but in performance, particularly done as expertly as tenor Jason Ferrante performed it Sunday, it works wonderfully well.

The story of The Consul is that of an unnamed Central or Eastern European nation where a freedom fighter named John Sorel is being pursued by the secret police. After a close call with them, he goes into hiding, telling his wife Magda to approach the consulate of a nearby nation with a request for help. Magda and John’s infant boy is being watched by John’s mother, but the child is not flourishing, and this adds to Magda’s stress when she goes to the consulate to get help but gets repeatedly blocked by a hyper-efficient secretary.

Menotti was an Italian composer, and though he studied in the United States and spent most of his career here (he was the longtime partner of Samuel Barber, with whom he lived for 40 years in a spacious house called Capricorn in Mount Kisco, N.Y.), his heritage and his instincts are fully that of the Italian operatic tradition as advanced by Giacomo Puccini. And indeed the hand of Puccini weighs heavily on this opera, but there are elements of Prokofiev and the more vinegary moderns in it, too, and while Menotti cannot quite meld his eclecticism into a highly distinctive style, he comes very close, and the music flows along logically and naturally.

Thomson, who sang the central role of Magda, was Tosca last season at FGO, and while her Tosca was admirable and well-sung, her Magda was even better. In “To this we’ve come,” with its air of thoughtful resignation and then fury at the dehumanizing effect of bureaucracy and paperwork, Thomson paced it superbly, building slowly from its initial conversational style to the big climax — “That day, neither ink nor seal shall cage our souls / That day will come.” As she got there, her voice bloomed and rang out, ending on its terminal A-flat with a sunburst of beautiful sound.

As John’s mother, the mezzo Victoria Livengood, a longtime Menotti collaborator, sang with a commanding, forceful voice that was particularly lovely in the lullaby to John and Magda’s son, “I shall find for you shells and stars,” with an especially pretty coloring in its lower registers. She brought deep feeling to the role and proved a conscientious actress all the way through, staying in character after the death of the baby and moving slowly off stage, weeping as she went.

Baritone Keith Phares was an excellent John, with a fine, well-rounded voice, and he was much more natural on stage than Thomson or Livengood, who seemed to be overly restricted by director Julie Maykowski’s initial staging of Act I, in which the two women seemed frozen by things that hadn’t happened to them yet. Mezzo-soprano Carla Jablonski was equally excellent as the Secretary, properly officious in her regular role and very sensuous in the dream sequence of Act II; her Act III arietta, “Oh, those faces,” gave the audience a good idea of the warmth of her large voice.

Ferrante, as I noted in passing earlier, was a terrific Nika Magadoff (the Magician), utterly at home with this part, tossing off the magic tricks with aplomb and singing with a sturdy, clear voice and crisp diction. In a debut performance, bass Tyler Simpson was a very fine Secret Police Agent, with a large, sonorous voice and a persuasive air of menace.

All the smaller roles were ably filled; Miami’s own Betsy Diaz, in the soprano role of the Foreign Woman, sang the Act I aria “Mio Signor, io vengo per mia figlia,” with her usual bigness, but also some darkness that made it more tragic. Bass-baritone Chance Eakin was a rather soft-voiced Mr. Kofner, while soprano Hailey Clark, singing a French chanson (“Tu reviendras”) as a cigarette-puffing worker on a smoke break (in the original show, it’s a voice on a record), showed off a strong and attractive voice.

Mezzo Kirsten Scott was a good Vera Boronel, and positive marks also go to soprano Rebecca Henriques as Anna and baritone Isaac Bray as Assan the glass-cutter. It should be noted that all the roles at the consulate — the Foreign Woman, Kofner, Vera, Anna and the Magician — turn into important ensemble roles for the trio, quintet and septet in Acts II and III, and the blend offered by this high-end chorus was beautiful to hear.

Maykowski’s stage direction, again as I noted earlier, was quite stiff in the beginning of Act I; all the action with Livengood and Thomson needs to seem a little more natural. But the staging of the dance sequences in Acts II and III was very effective, and there always was enough happening to direct the viewer’s gaze. One glitch at the end: The phone in the final seconds is far too soft and cannot really be heard above the orchestra, so it makes Thomson’s last gestures more mysterious than they have to be.

Conductor Andrew Bisantz does a marvelous job with this score, supporting his singers expertly and holding back the full power of the orchestra until the big climaxes really call for it. The orchestra played wonderfully well in a work that few of the musicians are likely to have known before these performances.

David P. Gordon’s set for the Seattle Opera is a beauty, with the Sorels’s apartment looking appropriately ragged and then turning to reveal the consulate, a grim stack of black filing cabinets reaching from floor to proscenium. It’s an unforgettably strong image, and yet despite its touch of absurdity is completely believable. Kevin G. Mynatt keeps the lighting in Intermediate Soviet Gray, and it adds creepily to the claustrophobia. He adds just the right touch of softness in the hypnosis scene, and has managed to find just the right shade of oppressive institutional yellow for the light in the consul’s office at the back of the stage.

This opera’s reputation as a big prizewinner (Pulitzer, Tony, Drama Critics’ Circle) brought it some backlash as a lightweight work, which is where critical opinion is on Menotti in general. It’s true that The Consul doesn’t probe as deeply as Wozzeck or penetrate with the pathos of La Bohème, but give it credit for what it is: A masterful work of stagecraft that has a lot to teach a younger generation of composers, directors and performers about how to put together a piece of theater that really works on stage.

FGO’s production of The Consul deserves your attention. There can be few later 20th-century or 21st-century operas that are as likely to please an audience as easily as this one does, testament in part to how well Menotti learned the lessons of Puccini, but more importantly a testament to Menotti’s own formidable craft, which because of its effectiveness in realizing his aims has surely been underrated.

The Consul can be seen at 8 p.m. Tuesday, Friday and Saturday at the Ziff Ballet Opera House, Adrienne Arsht Center, 1300 Biscayne Blvd., Miami. Tickets start at $21. Call 800-741-1010 or visit www.fgo.org.