When the student orchestra at New York’s Juilliard School gives concerts, audiences have to line up beforehand to get a ticket. But with free admission, it’s a pretty good deal.

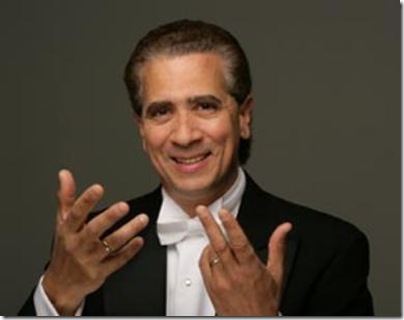

So when Guillermo Figueroa, who studied the violin at Juilliard, came to Lynn University to take over the conservatory orchestra, he was astounded and pleased to discover that its audiences in Boca Raton were just as enthusiastic as the ones at Juilliard — and they were paying for the privilege.

“I was blown away. I always tell people that we get packed houses. It’s virtually impossible to get a ticket the week or two before the concert, and people are paying to see a student orchestra,” said Figueroa over lunch in Boca Raton earlier this month. “It’s mind-boggling to me that there’s that kind of level of support and interest. It makes a lot of sense: It’s a very wealthy population, and wealthy often means pretty well-cultured. They did all this stuff back home, and they want to keep on doing it.

“It’s only in our best interest to keep on cultivating that,” he said. “It’s amazing.”

Tonight and Sunday, Figueroa leads the Lynn Philharmonia in a program that includes Elgar’s early Cockaigne Overture, the Brahms Fourth Symphony (in E minor, Op. 98), and Figueroa’s own mashup of two works by the contemporary Puerto Rican composer Ernesto Cordero: Ínsula Tropical, a combination of two movements apiece from two of Cordero’s concerti for violin and string orchestra, Ínsula and Concertino Tropical. Figueroa has recorded both works with the Croatian group I Solisti di Zagreb on the Naxos label (here is a performance of Ínsula, part 1 and 2) and will be the soloist tonight and Sunday afternoon.

Figueroa, a member of a distinguished Puerto Rican family of musicians that includes composer Narciso Figueroa (1906-2004), who did for the danza what Piazzolla did for the tango, and two cousins, violinist Narciso and cellist Rafael, currently playing in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. In 1981, 11 members of the family gave an all-Figueroa concert at Carnegie Hall.

“I would like to do bring my two cousins here at some point and do something. We play together a lot, and in that scheme, I pick up the viola, and Narciso plays the violin,” he said.

Figueroa has had a fine career as a violinist, having been the concertmaster of both the New York City Ballet Orchestra and the conductor-less Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, which he helped found, and which is today perhaps the best-known of all such groups that work without a music director. He expanded his horizons into conducting, and from 2000 until its bankruptcy in 2011, was director of the New Mexico Symphony in Albuquerque.

The programs Figueroa has chosen for the Lynn season all contain at least one contemporary work, and wrap up with a program of 20th-century American music.

The Oct. 25-26 concerts feature American composer Harold Farberman’s Triple Play, a clarinet concerto encompassing three clarinet styles: classical, jazz and klezmer. It will be played by three different student clarinetists, one for each movement.

“Why not? Get everybody involved,” he said.

The program also includes two canonical works, opening with Mozart’s overture to his German rescue opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail, and closing with the lush Rachmaninov Second Symphony.

After the conservatory’s concerto competition concerts (Nov. 15-16), which feature a handful of student winners over two days, the Philharmonia returns in February with the eminent flutist Jeffrey Kahner, who will play the Flute Concerto of the Iranian composer Behzad Ranjbaran, whose music has the flavor of his homeland as filtered through a Debussy-like sensibility, something along the lines of Enesco. Also on that program (Feb. 7-8) will be Lynn violist Ralph Fielding in Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, as well as the Italian Symphony (No. 4 in A, Op. 90) of Felix Mendelssohn.

Percussionist Edward Atkatz is the soloist March 21-22 in Christopher Rouse’s percussion concerto Der Geretette Alberich, which uses the music of Wagner to imaginative effect; Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony (in B-flat, Op. 60) and the ballet music from Mozart’s opera Idomeneo round out the concert. The final concerts on April 11 and 12 offer music from Leonard Bernstein’s score for Elia Kazan’s film On the Waterfront, the Third Symphony of Aaron Copland, and George Gershwin’s tone poem An American in Paris.

“Once I had the Copland, I thought, ‘Let’s go all the way. Let’s do all-American,’” he said. “And I have always wanted to do for years, but have never done, the ‘On the Waterfront’ music. I thought it would make a great pairing with ‘American in Paris,’” he said.

Figueroa is proud of the diversity of the programming.

“They need to know this contemporary music, and these four pieces just about cover the gamut. They are all so different from each other,” he said. “I am thrilled with the way it worked out. It looks like a really good mix.”

Then again, it’s important that future orchestral players know the standard repertoire.

“This is a training school, and they need to get out of here having played the basics,” Figueroa said. “So I made sure that we had a Brahms symphony, a Rachmaninov symphony, Mendelssohn, Beethoven and Berlioz. So we’re covered; we have a lot of great standards.”

This year, too, Figueroa has changed the way the orchestra rehearses.

“There may be others, but I had never seen a conservatory orchestra structured in a professional schedule. We don’t have orchestra every Tuesday and Thursday for two months and then play a concert. We only rehearse for that week, from Monday to Friday, like a professional orchestra,” he said. “It’s great training for the real world, because that’s what you’re going to encounter.”

He said there has been a debate in the conservatory about the best way to train the students, and he said he can see both sides of the argument.

“So we compromised. This year, we have started a new structure. The week before, we have sectional rehearsals, and one full-orchestra rehearsal as a reading of the material,” Figueroa said. “We read it on Thursday, and they have three days to absorb before we start rehearsal. But at least they’ve experienced the piece … so that by Monday, everyone is in a very different frame of mind than if it was just the first time they’d seen the piece.”

There has been an unmistakable improvement in the overall level of musical accomplishment among young players in the past 30 years, and Figueroa concurs that today’s rising players are remarkable.

“I don’t know that there’s anybody today that is like a Heifetz or a Milstein; that was a golden era of music. But there are more people today that are really good than at any another time in history,” he said. “You have to be a monster player to get a job even in a fifth-level orchestra. The good part of that is that you see a rise in the level of community orchestras; there are some really good orchestras out there.”

The downside is that it makes it immensely hard for young musicians to find steady work, given the uncertain state of many performing arts institutions today. “Some of these kids will get their bachelor’s, their master’s, their performance certificate, and they’re here eight, 10 years,” he said. “They want to get a job, but they can’t find one. It’s very difficult.”

Looking ahead, Figueroa would like to expand the conservatory’s reach, perhaps by bringing in dancers from the nearby Harid Conservatory, where Lynn’s conservatory originally was located. He also wants to involve the larger community as he did in Albuquerque, where in 2003 he organized a Berlioz Festival for the 200th anniversary of the birth of the French composer, who is Figueroa’s favorite.

“We brought in restaurants to do French dinners, we had lecturers from everywhere, even David Cairns, the Berlioz biographer,” he said. “We even had a lecture by the fire chief of Albuquerque — and people came — on fires and safety procedures in the Paris of the Berlioz era.”

It all comes down to engaging people, Figueroa said.

“Involvement, some kind of personal interest, is what brings the people in. It’s not just preaching … There’s something for you in the orchestra, and therefore you should support it,” he said.

“The key is to bring in the community around you by offering them something they wouldn’t have had otherwise. And making them interested, making them have a stake in your own survival.”

The Lynn Philharmonia performs at 7:30 tonight and 4 p.m. Sunday in the Wold Performing Arts Center on the campus of Lynn University in Boca Raton. Tickets range from $35-$50. Call 237-9000 or visit this link at events.lynn.edu.