Editor’s note: There are no new ideas in Hollywood – only new spins on old ones. This occasional column looks at new releases and argues why you should see old ones first.

Editor’s note: There are no new ideas in Hollywood – only new spins on old ones. This occasional column looks at new releases and argues why you should see old ones first. Stand-up comedians are self-absorbed, narcissistic, snobbish, petty, antagonistic people. It’s a blanket statement, but it’s born of a stereotype that I’ve found true no matter how many places I’ve seen them perform and no matter how many times comedians have been depicted in movies and television. When I visited New York’s Village Lantern a couple years back, an open-mic hack whose laugh-free act consisted of unpleasant jokes about bodily fluids and unsanitary derrieres physically attacked a heckler just inches from where I was sitting.

The incident gave me a great story, and like any good comedy story, it had a punchline: After the violent comic was thrown out, he showed up a few minutes later because he’d forgotten his phone, walking through the debris of toppled tables and even enlisting the help of the heckler to find it.

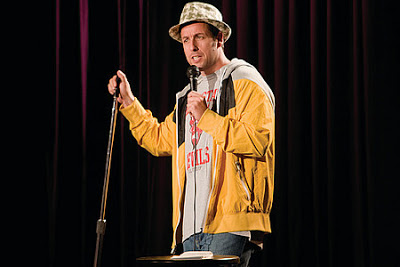

In Judd Apatow’s appropriately bitter Funny People, too, a couple of comedians engage in awkward fisticuffs. Apatow’s third movie is his weakest to date, but it understands the mentality of stand-up comedy and the people who try it better than any movie released in Hollywood.

Granted, there’s a short list to work with. Frank Whaley’s The Jimmy Show, about a comedian with a pathetic life who bombs on stage night after night, is so wrist-cuttingly depressing that its only appeal is that of pure Schadenfreude. Comedian, a documentary about Jerry Seinfeld’s return to the stand-up grind, shares as its subject an up-and-comer named Orny Adams, who epitomizes the very self-absorbed, narcissistic, snobbish, petty, antagonistic stereotype so many comics embody.

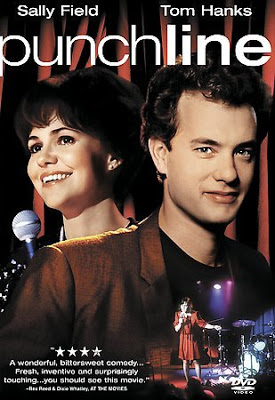

But the first modern Hollywood tale to explore the psyche of the comedian was 1988’s Punchline, which shares enough in common with Funny People that you might want to see it first. Both films feature established, curmudgeonly comedians who take inexperienced protégés under their wings.

In Punchline, it’s a cranky med-school dropout played by Tom Hanks who helps a bored housewife played by Sally Field hone a craft she isn’t very good at. In Funny People, it’s a comic-turned-actor played by Adam Sandler (who makes movies that are transparently similar to Adam Sandler movies), who, upon learning that he’s suffering from a life-threatening form of leukemia, enlists an aspiring comedian (Seth Rogen) to write jokes for him.

Both films understand that comics aren’t the nicest souls on the planet – Hanks has arguably never been as unlikable as his turn in Punchline, and Adam Sandler is more prickly and off-putting than ever in Funny People. We’re subjected to scenes of both men crashing and burning on stage. But the difference between these scenes best expresses why Funny People, for all its flaws (its length, its lack of comedic sharpness, its general slightness), edges out its predecessor in veracity.

When Hanks’ Steven Gold bombs, the moment is manipulative, overwrought and, like much of the film’s depictions of onstage performances, utterly bogus. It’s a cheap attempt to get us to feel some sympathy for the guy. When Sandler’s George Simmons has his meltdown in Funny People, it’s a Goldilocksian moment – not too much of a breakdown and not too little. It’s just right. I’ve witnessed breakdowns just like it.

So, too, have I witnessed real comedians whose acts are remarkably similar to the material and style of Apatow’s creations, such as Aubrey Plaza’s cute, droll Daisy and Aziz Ansari’s hyper, abrasive Randy. Their material isn’t as terrible as the crap you’re likely to hear at any of South Florida’s numerous open-mics, nor is it as funny as Apatow himself can be in his screenplays. In other words, it’s utterly believable.

Both movies have strong pedigrees by real-life comics: Punchline’s cast has the likes of Damon Wayans, Paul Mazursky and Taylor Negron, while Funny People includes cameos by Sarah Silverman, Andy Dick and Norm MacDonald. But only the latter proves worthy enough to include appearances by those self-absorbed, narcissistic, snobbish, petty, antagonistic people.

John Thomason is a freelance writer based in South Florida.