One of the joys of the annual Palm Beach Chamber Music Festival is its array of fresh programming, bringing little-known music out of the libraries and into the harsh light of the stage, there to make its way or not, as the case may be.

And this 21st season of the festival has been no exception, with rarely heard works dominant, and the familiar making itself known only very occasionally (Mozart’s G minor string quintet, Bartok’s Contrasts, and Schubert’s The Shepherd on the Rock). The fourth and final week of concerts in the series, which wrapped up Sunday afternoon at the Crest Theatre in Delray Beach, had two rarities on its first half and a chamber music staple on the second.

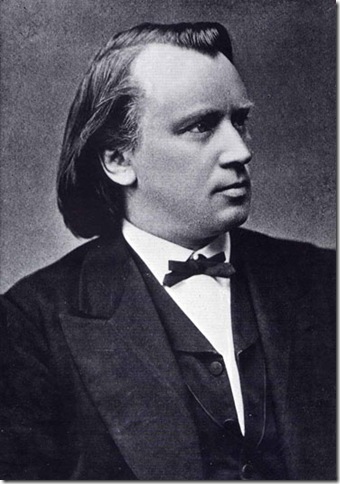

And it was that staple work, the Piano Quartet No. 1 (in G minor, Op. 25) of Johannes Brahms, that ended this year’s festival in such affirmative fashion. In her remarks to the good-sized house at the Crest, pianist Lisa Leonard confessed that when all is said and done, Brahms is her favorite composer, an admission that won a round of applause.

One of the other benefits of doing so much rare music besides finding hidden gems is that it helps us hear the strength of the masterpieces we cherish. That’s not to say the lesser-known music is ultimately not worthy; far from it: no doubt like many longtime attendees of these concerts, my own store of musical knowledge has been constantly enriched by hearing so many unusual pieces played so well.

But there is also a reason that works such as the Brahms quartet retain their power over the generations (it marked the 150th anniversary of its premiere last year). This is a composer with depth to spare and prodigious invention who far outclasses his contemporaries, even if his mode of expression can sound overly thick and clumsy in the wrong hands.

It was in the right hands here, with the four players – Leonard, violinist Dina Kostic, violist Rene Reder and cellist Susan Bergeron ― bringing to this piece a sober, tightly controlled reading that stayed out of Brahms’ way and let him do the talking. Certainly I’ve heard performances of this quartet that were more kinetic, but I enjoyed the straightforward way the four musicians presented it Sunday.

There were things that could have been done to make more out of the music that would not have conflicted with the overall approach here. The little pairs of two-note motifs at the end of the development section in the first movement (and that recur toward the end) deserved some more style, perhaps a stronger dynamic and a shorter articulation, to make them stand out. The Intermezzo second movement would have been better off, too, with a more nuanced opening; although Bergeron’s repeated Cs got things off on the right exciting foot, the rest of the movement needed some more lift and swing, and the trio more contrast. The ending of the movement, though, with Leonard’s arpeggios sparkling like pixie dust under the hush of the three strings, was nicely done.

The musicians were more relaxed and emotive in the third movement, which had some strong lyrical playing in the initial bars. The military march (in 3, but still march-like) was surreptitiously introduced by Leonard, and then opened up, but not as much as it could have ― there’s a certain weirdness about this movement that benefits from big gestures. In keeping with the general orientation of this reading, the finale was not as manic as I’ve heard it in other halls, but it worked well here. The repeated sixteenth notes that trade between the instruments were like a large ball passed between them rather than a furiously buzzing object that’s about to explode and which gets handed off as soon as possible.

The music had good pop-Gypsy flavor, 1860s-style, and by the time the ending came in sight, the musicians were cooking along admirably rather than racing each other to the finish line. Again, there’s something fun about hearing an on-the-edge-of-madness sojourn through this movement, but this firm, strong interpretation was more about the music itself than the performers, and that was all to the good.

The concert opened with one of the many chamber works of Alessandro Rolla, the early 19th-century Italian violinist and composer best-known for being the teacher of Nicolo Paganini. This sextet was a little unusual in its use of wind instruments ― scored for flute, clarinet, bassoon, two violins and viola― in the work of a composer who wrote primarily for his own instrument. And indeed, this work was primarily a concertante work, with first violinist Mei Mei Luo handling virtually all of the heavy lifting. And she handled it well, dashing off well-drilled figurations that helped this charming, lighthearted music sparkle.

The wind sextet (in B-flat, Op. 271) of Carl Reinecke that came next is a substantial work that comes close to Brahms in style and outlook, though without that composer’s distinctive personality. Still, this is a beautifully crafted and handsomely scored sextet, written by someone who knew how to write effectively for six instruments ― flute, oboe, clarinet, two horns and bassoon ― and combine them in a way that makes them sound large and rich.

Of particular note was the playing of the two hornists, Amy Bookspan and Maria Harrold Serkin. These are horn parts in the full German post-Romantic tradition (the sextet dates from 1904), and that means lots of notes, and lots of long legato lines. The two women played expertly throughout, with nary a flub or splattered note, and that’s critical for this music, which relies so heavily on the horn for its upholstery.

Flutist Karen Dixon led the way in the expansive, elegant first movement, playing with a capacious sound that opened the curtain for the music in a suitably expansive way, followed in due course by clarinetist Michael Forte and oboist Erika Yamada. The slow movement was plush and warm, and the march-like finale had a good sense of snap and high spirits.

The level of playing throughout was quite high, and Reinecke no doubt would have been pleased to hear a rendition of his work that was at once so faithful to his idiom and so carefully balanced and blended.