Nobody uses a 137-year-old silver set of 1,250 pieces from Tiffany & Co. to eat lunch anymore or gets a glossy water pitcher as retirement gift. A pen and porcelain plates will do.

Sometimes it takes such a decline in popularity to make an art exhibition happen.

If it wasn’t for silver’s falling demand, the current show at the Henry Morrison Flagler Museum may not have happened. Luckily, even things that last forever do not enjoy eternal fame.

Stories in Sterling: Four Centuries of Silver in New York opened in late January with an array of silver objects that once meant the world to someone but through time have been donated to the New-York Historical Society.

The shiny collection, on the second-floor galleries through April 20, takes us through four centuries of silver production and use in New York and the United States in general. The exhibit is broken into six sections that simulate the evolution of silver’s status and consists of pieces born to a time that cared about flaunting success. Never mind practicality and prudence. This was all about indulgence and extravagance.

Take a look at the hand mirror (first gallery room) made of electroplated nickel silver belonging to Louis W. Rice’s skyscraper line of dresser accessories designed in 1928. If it brings to mind the soaring skyscrapers of New York in the 1920s, you are not wrong. But it also speaks to the glamour of even personal objects that most likely would have never left the owner’s private room. Perhaps flaunting was not the only motivation.

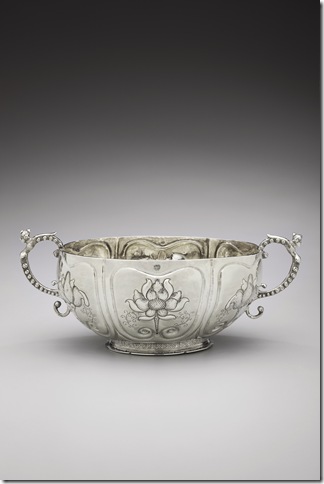

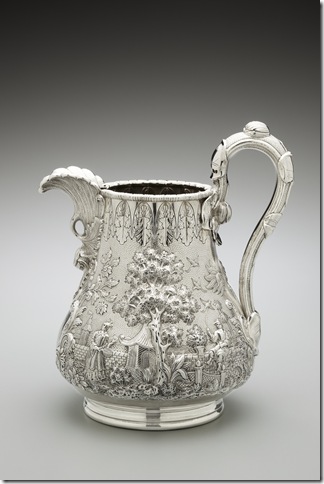

An 1850 water pitcher by Tiffany, Young & Ellis features a boy playing with flying birds and a woman holding a fan in what looks like a garden. There are plenty of trees and vegetation as well as a brick bridge. This Chinese-themed object is likely among the first silver pieces to get this firm’s mark. Near it sits a neoclassical tea and coffee service from 1859 by Gale & Willis. According to the description, the stamped symmetrical designs and hand-engraved details reflect a balanced marriage of mechanical precision and hand techniques.

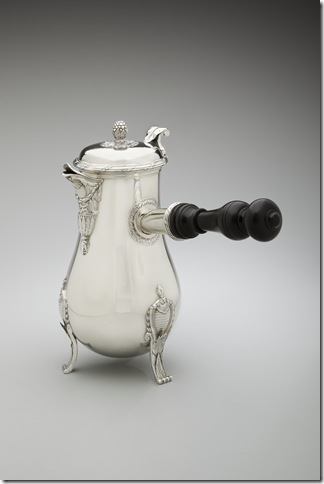

And in the east side of the room we find a dynamic teapot sporting bird claw feet and an eagle’s head spout. Captain William Bowne received it from the passengers of the Courier as a sign of gratitude for their safe passage from Liverpool to New York in 1819.

Silver was the perfect ego boost. Large pieces such as trophy cups provided a creative challenge for American silversmiths while giving the eventual owner something to show off. Size did not matter. Even the smallest pieces here, such as teaspoons, are packed with details.

Of the entire show it was the last two sections — “The Rituals of Tea and Coffee” and “Elegant Dining” — that I enjoyed the most. It may have something to do with my ice cream addiction and my romantic notion of tea time. The Tiffany ice cream dish appears heavy and carries such a serious air that it almost takes the fun out of an experience more associated with licking fingers and milk moustaches. Now consider that this is one of a pair commissioned by Marie Louise Mackay in 1877 as part of that 1,250-piece service.

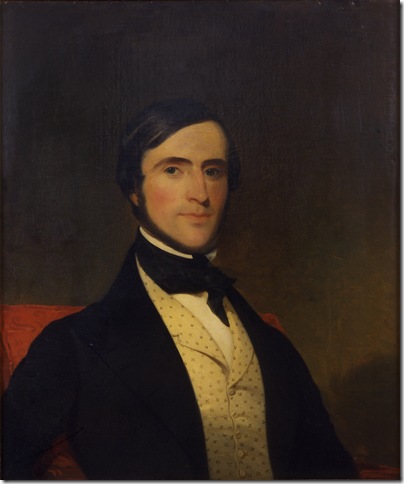

Accompanying the more than 100 items are portraits and photographs that provide historical background and context. And that is a good thing. Without the personal stories and historical background Stories in Sterling would have seemed a cemetery of cold polished stuff. Fortunately, the museum did a good job of giving the objects a heart.

For instance, take the 1589 beaker (an item typically used for beer drinking) in the first room. According to the description, this item was used by the Van Rensselaer family to remember the heroism of their patriarch, Captain Hendrick Van Rensselaer, who died in 1602 defending a Dutch city against the Spaniards. A clever phrase engraved on the underside advises drinkers to save their words of wisdom for sober times.

The exhibit’s unintended star, however, may be the amazing durability of this metal, although it is its fading popularity that impacted me the most. Seeing the effort put into creating, and acquiring, something desired by all once and most likely considered clutter now, made me momentarily sad.

But then I thought about the fact that even when these objects lost value they still held enough significance to be donation material. At least the New-York Historical Society thought so. Perhaps the matter is not whether silver will make a comeback or whether we have methods to deliver the message this metal once transmitted. We do have them. The question is: how do they compare?

Stories in Sterling runs through April 20 at the Flagler Museum. Regular ticket prices: Adults: $18; $10 for youth ages 13-17; $3 for children ages 6-12; and children under 6 admitted free. Hours: 10 am to 5 pm Tuesday through Saturday, noon to 5 pm Sunday. For more information, call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.