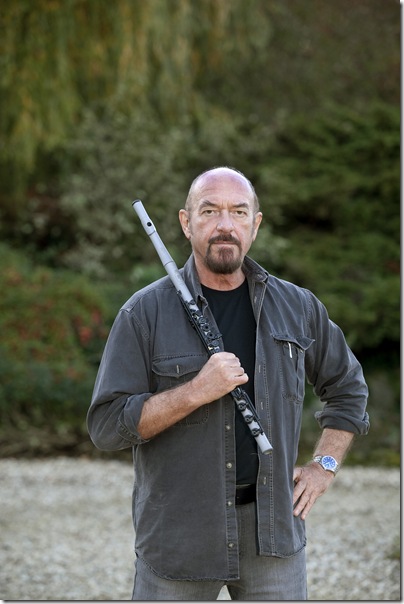

Add to the list of Woodstock-era rockers who are still performing live in concert at Social Security age the name of Ian Anderson, who brought the flute to rock music through his high-concept former band, Jethro Tull.

Forty years ago, he had an international hit with the progressive rock album Thick as a Brick, which he wrote with lyrics credited to a fictional 10-year-old prodigy named Gerald Bostock. This Wednesday evening, Anderson brings his new eponymous band to the Kravis Center to revive that earlier album and pair it with a follow-up, titled appropriately if not very imaginatively, Thick as a Brick 2.

With the sequel album and with the current world tour, you could say that Anderson has come full circle. Just don’t say it to his face.

“Somebody used the term and I instinctively bridled at this talk of ‘bookending’ my musical career,” he says by phone from his Northern England home. “That’s quite a horrible expression, because it does seem to suggest that you sort of put something on the front and the back and what’s in the middle is inconsequential. I don’t really like that idea.

“Talking about an album from this period of my life, in terms of nostalgia and retro, is not something I’m very comfortable with. Whilst I deliberately chose the same sound palette of instruments ― the jazz bass, the Les Paul Gibson guitar, the Hammond organ ― I mean these are instruments that have not only been around for a long time, but they’re still the weapons of choice for a contemporary rock band today,” Anderson, 65, explains.

“These are the classic rock sound palettes. Then you throw into that the flute, a little parlor acoustic guitar, the glockenspiel, those elements that, I suppose, are more associated with my music output over the years. I very deliberately and very carefully place those little reference points, wave that little flag and say, ‘Hey, remember me?’ But that’s like a little game you play with yourself and you share with the more knowledgeable members of your audience.”

Not only is the original Thick as a Brick album 40 years old, but except for the occasional small excerpt, it has been almost that long since Anderson has performed that single track, 44-minute composition in its entirely onstage. It is not that he had been avoiding it exactly, or only begrudgingly resorting to his old hits, like so many longtime rockers do.

“If you asked me to play ‘Bungle in the Jungle’ or ‘Teacher,’ it wouldn’t just be begrudging, it would be technically, mentally and physically impossible,” he says. “Because I just don’t find those pieces have any relevance for me ― lyrically or musically. I just can’t connect with them.

“Although we have in the past tried to play them, I just never enjoyed it. And there’s no point in going onstage and playing things you don’t enjoy. Happily, the big crowd-pleasers like ‘Aqualung’ and ‘Locomotive Bess’ and ‘Cross-Eyed Mary’ and, I don’t know, ‘Budapest’ and a bunch of other songs, they are songs that not only do I find the wherewithal to perform, but I really enjoy playing them, because they’re good songs and I’m very pleased.”

Puckishly, Anderson adds, “I mean, hey, I would love to play ‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ and, um, ‘Sunshine of Your Love,’ but unfortunately I didn’t write those ones. Somebody else did.”

Born in Scotland and raised in Blackpool, Anderson organized a couple of bands in his teens, but lightning did not strike until he noticed a flute hanging on a music store wall and decided to teach himself to play it.

“It just was an instrument that caught my attention for no good reason,” he says with a verbal shrug. It was just hanging there and I thought, ‘Hey, I wonder what that would be like.’ As long as I was pretty sure that Eric Clapton couldn’t play the flute then it seemed like a reasonable bet.

“As a third-rate guitar player, I didn’t really feel like I wanted to compete with either Eric Clapton or the rumored hot shots in London like Jeff Beck and Ritchie Blackmore and Jimmy Page. Living up in the north of England at that point, we were aware that there was some pretty scary new talent down there. It was a different kind of guitar-playing technique, a different approach. I didn’t really feel I was ever going to be in that league.”

On the other hand, he reasoned, he could be the best flutist in rock music, right from the start. “You know, to be a big fish in a small pool is sometimes a quicker way to getting noticed than just being one of the herd, to mix metaphors,” he says.

And so in 1968, Jethro Tull was born, an odd name for a rock band at a time when odd names were the norm. Curiously, though, Anderson concedes that he has never liked the iconic band moniker.

“We were given that name by our agent. I was a little uneasy about it, but I didn’t know why,” he recalls. “I didn’t realize at that point that we’d been named after a dead character from the history books,” a real-life 18th-century agriculturalist who invented the seed drill. “I thought it was just a name he’d made up. By the time I found out and we were then receiving the recognition as a new resident band at the famous Marquee Club (in London), it was a little bit too late to change.

“The name ‘Tull’ is a good West Country English name, a very old English name. But the ‘Jethro’ bit, you can’t escape that awful hillbilly kind of association. No, I am more than a little embarrassed about it and have been for 40 years,” says Anderson. “I have really very few regrets at all. Far and away the main regret is that name, but what can you do?”

The enigmatic Bostock character ― who will not be putting in an appearance at the Kravis ― is a symbol of the divergent paths we take in life to Anderson. So it seemed natural to ask him what he might have done for a living had he not become a rock performer.

“Well,” he responds without hesitation, “I had the pen in my hand, ready to put my signature on the application form to enroll as a police cadet many years ago. But that didn’t actually happen at the final second, not because I changed my mind, but the recruiting police inspector decided he didn’t quite trust my motives for wanting to become a policeman at that point in my life.

“I then went to try to get a job with the local newspaper, to train to be a journalist, but that didn’t happen. And I thought that I might be a farmer, but that didn’t happen. I also gave thought to perhaps being an actor. I would have given some thought to being an astronaut, except we didn’t have astronauts back then, and basically, I couldn’t climb up some stepladders without feeling a little giddy so I thought, ‘I’m probably not made of the right stuff.’

“So I didn’t go into space, although my flute did last year. One of my flutes spent five months in orbit on the International Space Station. A U.S. astronaut,” Cady Coleman, “kindly took it with her and played a duet with me from space on the night of the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gargarin’s first flight. I happened to be very close to where the original rockets were built, in Russia, where I was doing a concert that night. So we dueted by satellite and that was quite a landmark moment for me personally.”

No, astronaut Coleman will not be at the Kravis either, but Anderson feels confident that it will still be a concert well worth catching.

“I’m pretty confident from the show I’ve done so far in the last couple of weeks that what we will do will meet with a high level of approval,” he says. On second thought, Anderson adds, “It is just about expectations that either will be happily met or are so unreasonable in the first place that there’s not a hope in hell. If really depends on what they expect in coming.”

IAN ANDERSON PLAYS ‘THICK AS A BRICK, 1 AND 2’, Kravis Center Dreyfoos Hall, 701 Okeechobee Blvd., West Palm Beach. Wednesday, 8 p.m. Tickets; $25 and up. Call: (561) 832-7469.